Once again, after a rockier period, stories abound in the mainstream Pakistan media, as well as in the foreign press, about the revival of China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) projects in Pakistan. There have been articles and news stories in this regard ever since deals for $11 billion worth of projects were signed on June 25 and July 6. The new deals involve two hydropower generation projects costing $3.9 billion in the Pakistan-administered Kashmir region, and a plan to revamp the South Asian nation’s colonial-era railways for $7.2 billion – the most expensive Chinese project in Pakistan yet.

Along with the launch a special economic zone (SEZ) in Faisalabad, in the Punjab province of Pakistan, these developments have given new energy to CPEC, which had been on the back burner for some time. It is a push in the right direction in the terms of reviving CPEC on the parts of both Beijing and Islamabad.

The developments suggest that both sides want to move ahead, despite reservations emanating from both China and Pakistan. As a result, on the Pakistani side, retired Lt. Gen. Asim Saleem Bajwa has been made the chairman of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor Authority (CPECA) despite the opposition’s criticism of the very formation of the body.

Among other things, the CPECA provides the military a more formal role as a stakeholder overseeing related projects. This has been done for the purpose of smoothly running CPEC projects in Pakistan, where, according to Chinese thinking, the political governments are either weak or too short-lived. This creates bottlenecks in the implementation of projects in the longer run, at least from the point of view of China, where there is already an authoritarian regime. But the push to give the military control over Pakistan’s biggest economic and foreign policy initiative can further weaken the civilian set-up of the government.

It is interesting to note that the current border tension between China and India in Ladakh may have given a new push to CPEC projects in Pakistan. It may explain why China and Pakistan went ahead with the aforementioned deals in Pakistan-administered Kashmir, which India has reportedly opposed. Ladakh is part of the greater Kashmir region.

During Pakistan Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi’s short but important visit to China in late August, he and his hosts discussed the Kashmir question, which Pakistan welcomed as part of its efforts to bring international attention to the issue. In addition, both sides underscored that CPEC has entered a “new phase of high-quality development” and will continue to play an important role in supporting Pakistan to overcome the impact of COVID-19 and achieve greater development. They also agreed that the timely completion of projects planned under CPEC Phase II “is one of our top priorities.”

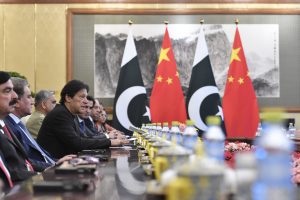

To many Islamabad based analysts, recent events signal that after a hiatus of few years, CPEC has once again become one of the top priorities for Islamabad. The project had somewhat slipped out of Prime Minister Imran Khan’s narrative after he assumed the office in 2018. But keeping in the view the recent CPEC developments, analysts argue that CPEC is back and bigger than ever, thanks to both internal and external developments. Like his predecessor, former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, Khan apparently realized that CPEC is significant to his cash-strapped country, no matter on how much it makes Islamabad dependent on Beijing in the long term.

In the past, in part motivated by his political rivalry with Sharif, Khan struggled to review and revisit CPEC terms and conditions with the government of China.

Beyond that, however, Khan has long idealized Malaysia’s former Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, who had demonstrated his open opposition to the Chinese domination of the Malaysian economy, fearing Chinese loans would push his country toward a debt trap. But given the recent deals and developments surrounding CPEC, Khan must have realized that he cannot be the Mahathir of Pakistan when it comes to the opposition of Chinese influence.

Over the years, it has become clear that China’s Belt and Road Initiative is not only evolving China-Pakistan ties but is also impacting Pakistan’s ties with its neighbors, particularly Iran. An 18-page draft an economic and security agreement between China and Iran — if materialized — has the potential of significantly impacting Pakistan.

Over the years, things between Iran and Pakistan have gone from bad to worse. Mutual distrust, cross-border militancy, and sectarianism plague relations between the two countries. This begs the question: Will a China-Iran deal further push apart Pakistan and Iran, or bring them together under China’s wings?

According to the leaked draft agreement, China could be spending a sum of $400 billion in Iran — which is much higher than Beijing’s investments in CPEC projects in Pakistan. That suggests China would be giving more significance to Iran than its all-weather friend, Pakistan. At the same time, Iran has also pushed aside India in its Chabahar port, which is situated just 72 kilometers away from Pakistan’s Gwadar port in Balochistan.

On the other hand, there are reports that Beijing has other plans to develop ports on the Iranian side. One of the important ports is Bandar-e-Jask, situated over 200 kilometers from Chabahar and outside of the Gulf of Hormuz, a narrow stretch where ships carrying most of the world’s oil transit. If China invested in this port, independent analysts are of the view that this could potentially reduce the significance of Gwadar port — the backbone of CPEC projects in Pakistan.

On the other side, the United States is already complaining about increasing Pakistani engagement with China in the region. The U.S. is already unhappy with CPEC in Pakistan, and it has lambasted the multibillion-dollar project on several occasions, including in the press. The recent CPEC deals are expected to push Pakistan further into Chinese camp, to the point of antagonizing Washington.

The United States has reportedly shown its opposition to the leaked China-Iran draft agreement, as the Trump administration has doubled down on its sanctions regime against Iran. Pakistan cannot afford to stand against U.S. interests in the South Asia region. Due to U.S. opposition, Pakistan previously gave up on a gas deal with Iran, despite Iran’s completion of work on its own side.

There are also serious obstacles to CPEC within Pakistan itself. Baloch separatists have targeted Chinese interests in Pakistan, which has raised the stakes for China’s Belt and Road Initiative in the country. A case in point is the June 29 attack by Baloch separatists on the Karachi Stock Exchange, which is 40 percent owned by a consortium of three Chinese burses.

Chinese are also working on CPEC projects in Sindh province, and there have been minor sporadic attacks on Chinese workers and installments by Sindhi nationalist groups as well. But more than Sindhis, Baloch separatists are targeting China’s interests in Karachi, the most populous city of Pakistan situated in Sindh province.

Following the recent attacks in Sindh, security officials are of the view that Sindhi and Baloch separatists are forming links, to carry out attacks. Although there is no solid proof, it seems the militants opposed to projects under the CPEC umbrella are coming together in their opposition and attacks. Thus, security official predict such attacks may pose a greater threat in the future.

But despite these international and domestic challenges, in Pakistan, CPEC is back on track with full speed. At the same time, one cannot ignore the looming headaches in the form of regional geopolitical tensions, and domestic security threats. Can CPEC overcome the threatening developments hovering over its head to succeed in Pakistan? Or is it fated to be put on the backburner again in the future?