Against the backdrop of a rapidly deteriorating U.S.-China relation there is an increasing interest in what a recent Diplomat article referred to as “the European theater in the emerging Cold War.”Looking at Europe-China ties since the 1990s it becomes clear that the recent tension is driven by deeper structural factors — and is therefore likely to stick. Despite its limited military relevance to Asia, the economic weight of the European Union (EU) means it can play a critical role in the global balance of power depending on the extent to which it leans toward the United States or China.

European attitudes toward China are undoubtedly hardening across the continent, including in key countries such as Germany. News articles on the topic tend to refer to China’s recent diplomatic missteps, from its infamous “Wolf Warrior diplomacy” to its often poorly received “mask diplomacy” since the outbreak of COVID-19 as well as European disapproval of the National Security Law for Hong Kong.

But looking beyond recent headlines to the development of Europe-China ties since the 1990s it becomes clear that the recent shift is driven by deeper structural factors and is therefore likely to stick.

When the Chinese military violently crushed demonstrations in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in 1989, the 12 countries of the European Economic Community (EEC), predecessor to the European Union, introduced sanctions along with the rest of the Western world and made various demands of Beijing that were never likely to be met.

China’s leader at the time, Deng Xiaopeng, correctly understood the importance of the lure of the Chinese economy on Western business interests in shaping policy toward his country. He admonished the leadership to stand firm and count on foreign businesspeople to pressure their governments to improve relations with China. This strategy worked remarkably well on European governments. After Deng’s Southern Tour of 1992 got economic reforms back on track, trade between China and the EU took off and European investments poured into China.

The effect on politics was clear. European governments dropped sanctions and focused on strengthening economic ties. In 1997 the EU produced what can be considered the last gasp of the post-Tiananmen human rights policy. Unsupported by most other EU-states, Denmark and the Netherlands stuck their necks out in the U.N. Human Rights Council by tabling a motion critical of China. The motion failed and China threatened retaliation. Business groups in both countries complained about their government’s China policy. The chairman of the Netherlands’ main employers’ organization went so far as to publicly demand “discussions” with the government on the handling of sensitive issues. In the years after, human rights issues were mostly relegated to an inconsequential “human rights dialogue” while the EU and China between them built one of the world’s most important economic relationships.

This happened at a time when European governments believed, as U.S. President Bill Clinton professed to do, that China would continue reform until it became a free market economy. European companies in China made money but were often frustrated by significant restrictions on their operation, unclear regulations, and inadequate protection of their intellectual property rights. However, these problems were regarded as temporary nuisances that would be remedied by ongoing reform, which in turn would be locked in by China’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001. After the EU had concluded its WTO accession agreement with China in May 2000, the head negotiator on the EU side, Pascal Lamy, told the China-Britain Business Council:

China’s entry into the WTO will bring vastly improved access for EU firms to China’s market. The costs of exporting to China will be less, as tariffs and non-tariff restrictions are sharply reduced. And the incentives to investing in China will be enhanced by a more attractive, and more predictable, business environment.

The expectations of growing and increasingly easy business with China were a strong force in shaping accommodating policies in EU capitals as well as Brussels in the ‘90s and ‘00s. There were problems in the relationship, of course, both those experienced by European business as well as those generated by an enduring public interest in China’s human rights situation. But the overall expectation among political elites was that these would be solved with time and, moreover, that engagement with the EU would itself help push China in the right direction. The result, according to one critical study from 2009, was a policy of “unconditional engagement.”

Fast forward to 2020 and the situation has changed. To be sure, China remains attractive to European companies. Recent Business Confidence Surveys conducted by the European Chamber of Commerce in China found that roughly 60 percent of their respondents stated that China would remain a top-three destination for current and future investments. However, they also found that half of respondents believed the regulatory environment would worsen in the next five years despite repeated promises by the Chinese leadership of continued opening. European FDI flows into China have declined after 2013.

Increased Chinese investment in the EU since 2012 has been distrusted as much as welcomed. Chinese investment, often financed by state banks under government programs such as Made in China 2025 and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), was seen as potentially politically motivated and market distorting. Influential business groups such as BDI and Business Europe and think tanks like the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS) have published papers urging policymakers to pay more heed to the long-term challenge posed by China’s state-driven economic model. A 2019 paper summarized the problem as follows: “At China’s scale and weight in marginal global growth, distortions and policy shortcomings that were once tolerable now are existential challenges for foreign counterparts.” Meanwhile, China’s recently announced reduction of limitations on foreign investors once again fell short of expectations.

At the same time, there appears to be a modest revival in attention paid to human rights and related issues on the European side. European responses to the situation in Hong Kong, though not nearly as strident as those of the United States, indicate that the EU is not likely to agree that this is an internal matter for China only. The EU has also openly criticized the persecution of the Uyghurs. Given the severity of what is happening in Xinjiang this may sound unsurprising, but in the previous decade such criticism may well have been relegated to working-level talks and given behind closed doors only.

Less well-known human rights issues have proved to be a sticking point too. The issue of kidnapped Swedish bookseller Gui Minhai has led to a substantial deterioration in China’s relation with Sweden, despite creative efforts by China to make the problem go away. The old issue of Tibet, an irritant in relations between many Western countries and China around the turn of the century, remains on the agenda as new Tibet support groups have recently been set up in the parliaments of the Czech Republic, Sweden, Lithuania, and France.

The EU and its member states are unlikely to join the United States in a repeat of the Cold War. European governments as well as the EU have continued to state that China remains an important partner both for bilateral cooperation as well as for tackling global issues like climate change. In addition, Europe is pluralistic and countries like Greece, Italy, and Hungary remain mostly positively inclined toward China. Nevertheless, EU-China relations are clearly on a downward trajectory for reasons beyond recent U.S. prodding and ham-handed Chinese diplomacy.

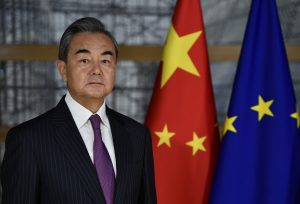

For China, this means that a single diplomatic charm offensive from Foreign Minister Wang Yi is not likely to do much to arrest the decline in its relation with Europe. For the United States, it means there is fertile ground for coordination with the Europeans on issues of shared concern, provided the next administration chooses to be less antagonistic toward them.

Laurens Hemminga is a Ph.D. candidate researching EU-China relations in the Department of Asian and International Studies at the City University of Hong Kong.