Leading up to the 2016 presidential election in Taiwan, then-candidate Tsai Ing-wen pledged to legalize same-sex marriage if elected. According to the Taiwan Social Change Surveys from 2012 and 2015, such legalization was supported by a majority of Taiwanese, with little variation in support by party. However, as opposition grew, largely on partisan lines, the future of legalized same-sex marriage was less certain. A May 2017 Constitutional Court ruling found the civil code limiting marriage to heterosexual couples to be unconstitutional, but the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP)-majority legislature did not pass legalization until two years later.

Over a year since legalization, has public opinion changed? Some within the Taiwanese LGBT community have felt more comfortable coming out to their coworkers after legalization, but the overall improvement in their daily lives is limited. Taiwanese who come out at work may still face discrimination or prejudice from coworkers. And legalizing same-sex marriage was not a complete victory: Heterosexual couples are still afforded greater rights with regard to adoption, and transnational same-sex couples cannot marry in Taiwan unless both countries recognize same-sex marriage.

As for the Taiwanese public, opposition sentiment fueled successful anti-LGBT referendums and KMT successes in local races in 2018. But Tsai’s decisive re-election victory with a continued DPP majority in 2020 suggested that the salience of this issue was not enough to sway uncommitted voters. Anti-LGBT campaigns emphasized the decline of traditional values and procreation, along with a litany of societal ills that would fall on Taiwan, yet these fears have not materialized with legalization.

This would suggest perhaps that some who opposed legalization may soften their position over time, as seen in other countries. For instance, in the United States, public approval of same-sex marriage improved after its legalization. Similar trends have occurred in European countries where same-sex marriage is legal. However, as seen in South Africa, which legalized same-sex marriage in 2006, and Ecuador, which legalized same-sex marriage in 2019, public opinion does not always improve after legalization. One survey in Taiwan found that 93 percent of respondents felt their lives had not been impacted by the legalization, but when asked about the impact on Taiwanese society as a whole, only 50.1 percent indicated no effect, while 11.9 percent said the overall social impact was positive, and 28.4 percent said it was negative.

Our original survey work from December 2019 asked, “Since the legalization of same-sex marriage in May of 2019, has your opinion of legalization changed?” We found that 19.3 percent had changed their mind, mostly switching to oppose legalization. Of those that did not change their opinion post-legalization, 28.4 percent opposed legalization, compared to 54.6 percent of those who had changed their mind. In contrast, 42 percent of respondents who had remained firm on their position supported legalization, while only 27.8 percent of those changing their opinion to now supported legalization. Such shifts suggest the saliency of efforts by opponents to frame legalization as an attack on traditional values.

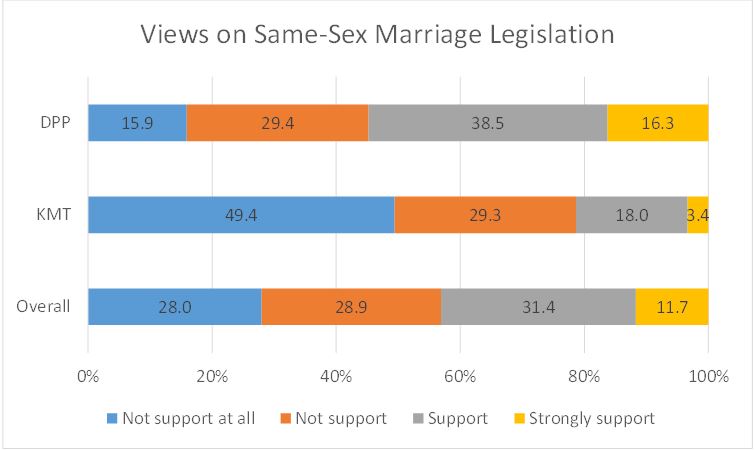

Recently released survey data from the Taiwan’s Election and Democratization Study (TEDS2020) suggests a continued polarization. In it, 1,680 Taiwanese were asked:

“On May 17th last year, the Legislative Yuan passed the same-sex marriage law (Enforcement Act of Judicial Yuan Interpretation No. 748, Same-Sex Marriage). Do you support this legislation?”

Excluding those that did not provide valid answers, we find a majority not in support of legalization (56.9 percent), with KMT supporters more opposed (78.7 percent), while a majority of those supportive of the DPP were also supportive of legalization (54.8 percent). That over 40 percent of DPP identifiers surveyed still opposed legalization also suggests that the party may be reluctant to promote broader LGBT rights if doing so may push some of its traditional supporters toward other parties.

Additional statistical analysis largely finds the same demographic factors influencing support in Taiwan as seen elsewhere. In particular, age negatively corresponds, and both education and income positively correspond, with support. Specific to Taiwan, supporters of Taiwan independence rather than unification with China or the status quo were more supportive, even after controlling for party identification. Moreover, compared to atheists, we find Protestants, Buddhists, Taoists, and followers of I-Kuan Tao (一貫道) were correlated with statistically significant declines in support, but that Catholics and followers of folk beliefs were not.

Unfortunately, the TEDS survey does not ask an important intervening factor: Do respondents know a Taiwanese person who is LGBT? Previous research in Taiwan and elsewhere suggests that those who know an LGBT person are more supportive of legalization and LGBT rights more broadly. Yet, even this measure may be problematic in that knowing an LGBT person is likely also conditioned by other factors such as religious identification (religious conservatives in Taiwan may not realize someone in their family or community is LGBT). LGBT people may not come out to those that have espoused intolerance. To increase support for same-sex marriage, one option available to Taiwanese activists is increasing and improving the portrayals of LGBT characters on TV and in movies. Characters who are well-developed and portrayed in a positive light might be useful introductions for those who do not personally know members of the LGBT community.

Seeing that mobilizing opposition to same-sex marriage did not lead to KMT electoral success in national elections, does this mean the KMT and like-minded parties would have less incentive for such a strategy in the future? This is harder to say. If KMT officials blame the election losses not on their message, but on factors such as the generally negative view among independents of their candidate, Han Kuo-yu, continuing with anti-LGBT appeals may well continue and prove successful. This is especially relevant in local elections rather than national ones, where concerns other than Taiwan’s relationship with China play a larger role in candidate platforms. However, this analysis still ignores the demographic challenges facing the KMT. The party has struggled to appeal to younger voters, a demographic more likely to support LGBT rights. For example, in the TEDS survey, 77.95 percent of respondents in their 20s and 66.24 percent of those in their 30s supported the legalization of same-sex marriage. Only 12.75 percent and 9.88 percent of these groups identified with the KMT, roughly a third of the rates of support for the DPP in those age groups.

Ultimately, it may be too soon to identify to what extent views on same-sex marriage will shift post-legalization. Research prior to legalization suggested, for example, that the framing of legalization could depress support, which may partially explain the KMT’s success in local elections in 2018. That one in five changed their view post-legalization further indicates the importance of media and elite framing. However, proponents should not simply assume that support will increase in the short term due to favorable demographic shifts and the gloomy predictions of opponents failing to occur. So far, messaging from supporters of same-sex marriage has had far more limited media coverage than their opponents. Thus, proponents should find creative means to frame legalization as consistent with Taiwanese values that may appeal to those whose views have not hardened.

Timothy S. Rich is an associate professor of political science at Western Kentucky University and director of the International Public Opinion Lab (IPOL). His research focuses on public opinion and electoral politics, with a focus on East Asian democracies.

Isabel Eliassen is an Honors undergraduate researcher at Western Kentucky University majoring in International Affairs, Chinese, and Linguistics.