In the first six months of 2020, as it was struck by the COVID-19 pandemic, Singapore’s foreign workforce shrank by 75,700. In an interview with local media, Manpower Minister Josephine Teo said that “it’s very clear that in recession times, foreign employment has served as a buffer,” given that foreign workers are the first that employers have to let go when business conditions worsen.

Foreigners without permanent residence make up roughly 30 percent of Singapore’s population of 5.69 million. These figures already reflect the 0.3 percent decline in population growth recorded in the census of June 2020, largely due to the reduction in foreign employment in the services sector due to COVID-19.

Singapore is a wealthy country whose per capita income towers over those of its neighbors in Southeast Asia. The city-state attracts migrant workers from less developed nations in search of greener pastures. As a bustling global corporate and financial hub, Singapore also grants foreign investors extra incentives to hire international talent in order to plug skill gaps and make up for supply shortages.

Now, with the COVID-19 pandemic buffeting the economy, Singapore is safeguarding the jobs of its own people at the expense of its foreign workers.

Singapore authorities predict that the country will experience an economic contraction of between 5 and 7 percent in 2020 due to COVID-19. To counter this recession, the government has announced four installments of economic stimulus totaling 100 billion Singaporean dollars amounting to around 20 percent of its GDP, with more than half of it drawn from past reserves. Of that, 80 billion Singaporean dollars will be used to save Singaporean jobs and businesses.

Unemployment rate among citizens and permanent residents rose to 4.5 percent in August, the highest since the global financial crisis, when overall unemployment rate peaked at 4.9 percent. With the monthly unemployment rate gradually rising, the Singapore government has prioritized the protection of its local workforce. Various measures have been put in place to benefit Singaporeans and permanent residents: a job support scheme that covers up to 75 percent of monthly wages from April 2020 to March 2021; more than 8,000 traineeships for recent graduates, with 80 percent of the training allowance co-funded by the government in partnership with participating companies and institutions; and a promise to create 10,000 permanent positions over the coming year.

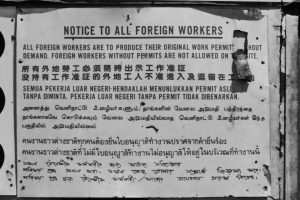

While the government has been offering employers in select vulnerable sectors a series of levy waivers and rebates to keep migrant workers and continue operations, it has also tightened the already stringent policies on issuing new work passes, which are necessary for the recruitment and retention of foreign mid-skilled workers and professionals. From September 1, qualifying salaries required for the sponsoring of foreigners have been raised, in addition to a more rigorous scrutiny of candidates’ academic and employment history. To qualify for an Employment Pass, a work pass issued to expatriates occupying managerial and executive roles, the minimum monthly salary requirement has been raised to SGD 4,500, up from SGD 3,600 at the beginning of the year.

These labor policies are congruent with the broader commitments that the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) made when it was returned to office at elections in July, when it assured Singaporean citizens that their grievances about workforce conditions had been heard and that solutions were underway.

During the special television and radio broadcasts that were held prior to polling day – a replacement for the physical rallies ruled out due to COVID-19 – immigration policy in general, and Singaporean citizens’ competition for jobs with foreigners in particular, were the focus of many election pitches. Opposition parties alleged that foreigners were displacing Singaporeans in PMET (professional, managers, executives and technician) roles and that their presence in the job market had depressed local wages. As one opposition party representative said, “a government is like a father to its citizens. And a father who provides for alien children while allowing the breakfast, lunch and dinner of his own children to be stolen, is a bad father.”

Singapore has recorded 58,043 COVID-19 infections with only 66 active cases as of November 6. Up until the beginning of April, the country had fewer than 1,000 cases and was praised by the international community for its aggressive contact tracing and isolation of new coronavirus cases. By the end of the month, however, the number of cases had jumped to more than 17,000, forcing the government to authorize strict containment measures akin to a lockdown. The vast majority of the cases, which now account for more than 90 percent of country’s total infections, affected low-wage migrant workers in overcrowded dormitories, most of whom are employed in the construction sector. The government has since managed to control the outbreak with mass testing and systematic quarantine strategies, along with promises to improve living conditions for migrant workers moving forward.

Of the 1.36 million foreign workforce population in Singapore, nearly a million are work permit holders, the majority of whom work as foreign domestic workers or are employed in the CMP (construction, marine shipyard, process) sectors. The surge in COVID-19 cases triggered long standing debates over the reliance of Singapore on low-cost foreign workers who are eager to fill manual labor jobs such as construction, security and cleaning that most locals are unwilling to take on. Acknowledging current realities, political observers have called for making these labor-intensive industries attractive to Singaporeans through the automation of processes and the guarantee of future career progression.

The remainder of the foreign workforce population in the country are foreigners occupying professional positions in various multinational companies and institutions, whom the government has been successful in attracting to Singapore. Recognizing that the local workforce may not completely meet the demand for the right set of skills and experience at the present time, companies, subject to manpower policies, are allowed to hire foreign professionals to meet their commercial objectives. However, with current measures aimed at shoring up local hiring, foreign jobseekers are now forced to navigate a more competitive labor landscape.

Singapore’s economic model has long hinged on its openness to global capital and its liberal policies toward foreign workers. Migrant workers have helped erect the city’s skyscrapers while international talent has played an important role in increasing the economy’s competitiveness. But Singaporeans’ call for an equitable balance between foreigners and locals in the labor market has never been as loud as during the pandemic. In his Parliamentary Address in September, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said that “we may be under stress now, but we cannot afford to turn inwards. We will adjust our policies to safeguard Singaporean jobs, but let us show confidence that Singaporeans can hold our own in the world.”

Mary Manlangit is a Filipina international relations professional based in Singapore. She is a postgraduate alumna of S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies at Nanyang Technological University.