In his inaugural address to the Diet last month, Japan’s Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide officially announced that his government would revise the country’s carbon-neutrality commitments, aiming for zero emissions by 2050. Suga expressed his intent to “put maximum effort into achieving a green society,” framing Japan’s inevitable shift to clean energy as an opportunity for post-COVID economic recovery and stating that the country would “need to change our thinking and realize that structural changes in industry and society will lead to significant growth.” In line with that pledge (and with the government’s regular triennial policy review), changes are expected to the envisaged shares of power generation across multiple sources as stipulated within Japan’s Basic Energy Plan.

Many would argue that one of the areas most in need of a rethink is the role of nuclear power in the country’s overall energy mix, whether reduced or increased. However, there has already been some confusion as to the exact role of nuclear power in achieving the government’s new targets. Suga himself did not rule out the construction of additional nuclear power plants, and Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) Upper House secretary-general and former head of the Ministry for the Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) Seko Hiroshige suggested that Japan would need to “promote the resumption of nuclear power plants while keeping in mind their safety and also consider building new plants that incorporate new technologies.”

The very next day, however, Chief Cabinet Secretary Kato Katsunobu stated in no uncertain terms that the Suga government was “not considering the construction of additional nuclear power plants,” at least at this stage. Kato suggested that new renewable sources and existing nuclear power plants would do most of the heavy lifting in terms of energy generation. Minister for the Economy Kajiyama Hiroshi echoed Kato in suggesting that the lack of public trust in nuclear power effectively ruled out introducing new plants, but said nothing about the role that existing facilities could play in meeting Japan’s new carbon neutrality targets.

Mixed messaging and divergences in views amongst government ministers on the role of nuclear power in Japan’s energy and environmental futures are not new, and it seems that the Suga administration intends for nuclear energy to play at least some part in meeting the 2050 target. The question seems to be for how long nuclear energy could or should contribute to those efforts. According to the government’s Strategic Energy Plan of 2018, nuclear will account for between 20-22 percent of Japan’s overall energy mix by 2030, a level which could presumably be sustained by an updated policy just as it was between the government’s 2015 and 2018 documents. At the same time, the government’s ongoing commitment to nuclear power contrasts poorly with a growing number of unfavorable facts on the ground.

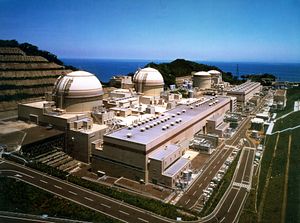

Most of the country’s reactors have remained dormant since nation-wide shutdowns in May 2012 and September 2013 following the disastrous events of March 11, 2011 at Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, with only a handful successfully restarted since August 2015. Of the 54 reactors in Japan prior to Fukushima, only nine have resumed operations while at least 21 are slated for decommissioning. Nuclear energy reportedly accounted for only 7.5 percent of Japan’s total power output in 2019, and as little as 3 percent this year so far – a tenth of the percentage supplied prior to Fukushima. That Japan’s imports of nuclear fuel from abroad were almost zero last year is some indication of the industry’s struggles, while the removal of nuclear energy from Japan’s power mix is a major reason why the country’s energy self-sufficiency rating has dropped to less than 10 percent (down from 20 percent), the second-lowest amongst OECD nations. If new power plants are ultimately ruled out and the current 60-year cap on plant operating lifespans is maintained (nearly half of Japan’s current reactors are already over 30 years old), then the future of nuclear power in the country is already on limited time. As a result, its share of the country’s overall energy mix is likely to shrink as 2050 approaches.

Public opposition, shrinking profit margins, and stricter safety requirements introduced by the Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA) have hampered efforts by Japan’s power companies to restart many of their nuclear reactors. The plight of Kansai Electric Power Company captures the challenges that Japan’s power companies face in trying to make a return on capital-intensive investments in such an uncertain environment. In April last year, the NRA refused to extend deadlines for the installation of mandatory anti-terrorism measures at all reactor sites, even after many of Japan’s power companies indicated that there was little chance of meeting those deadlines. In March this year, three reactors operated by Kansai Electric faced extended closures after a fatal accident at Takahama Nuclear Power Plant. Operations at another site were suspended in early October because of delays to the construction of anti-terrorism safeguards, while two reactors at its Oi nuclear power plant will also be taken offline this month, meaning that all of Kansai Electric’s power plants will be offline.

While the coming suspensions will not adversely impact Kansai Electric’s capacity to generate power, its relatively high dependency on nuclear power as a profit maker will undoubtedly see its bottom line take a hit. The company has also recently been rocked by corruption scandals dating back to the 1980s, further damaging the industry’s already tainted public image. With the costs of additional mandatory safety features now nearly equaling the costs of building a new reactor, drawn-out regulatory processes, a decline in local industry expertise and talent, and with local political and public opposition remaining relatively strong, there will likely remain a notable lack of incentives for power companies to invest in building new reactors without reform to the business environment.

Importantly, it seems as though the next generation of LDP leaders are embracing both carbon neutrality and the elimination of nuclear energy. Like Abe governments of the recent past, Suga’s cabinet features two particularly prominent politicians and possible future prime ministers who have stated their anti-nuclear preferences before, one of whom – Koizumi Shinjiro – is also the incumbent minister for the environment. Though the Environment Ministry does not officially set Japan’s energy policy, Koizumi has nevertheless been a driving force behind many of Japan’s recent environmental and clean energy initiatives since assuming his post in September 2019, including the revision of Japan’s decarbonization target.

In that respect, Koizumi has also been a vocal supporter both of Japan’s decision to more tightly regulate the country’s exports of coal-fired power stations and of reducing the country’s own reliance on those facilities. Koizumi has also proposed easing restrictions on building solar and wind turbine sites in Japan’s national parks, part of a solution to get around the challenge that Japan’s land scarcity has posed to the mass introduction of renewables. Though he has made no extensive public comment on phasing out nuclear power since his inaugural press conference last year, that silence may in itself may be an indication that Koizumi’s views on a nuclear phaseout remain unchanged even in the wake of more ambitious climate targets.

Of course, the nuclear lobby’s entrenched interests at the highest levels of the government and within the LDP itself will likely continue to frustrate efforts to comprehensively revise Japan’s nuclear energy policies. Indeed, there is every chance that the revised Basic Energy Plan due next year will maintain, if not expand, the share of Japan’s energy mix allocated to nuclear power. Still, without significant changes to the regulatory environment, a more favorable business environment, or a major shift in public opinion or political support, at present it is difficult to see Japan’s nuclear power industry making a major contribution to Japan’s carbon-neutrality goals in the coming decades.

Tom Corben is a resident Vasey Fellow with Pacific Forum.