For China, the geoeconomic policy principles behind the Iron Silk Road rail link through Central Asia were to provide China a hedge against its reliance on Pacific Ocean economies in the event of trade tensions. However, 2020 demonstrated that the Central Asian states have no hedge against the geoeconomic risk of relying on China as a trade partner. On the China-Kazakhstan border, rail freight wagons and trucks have been backed up for over a month as China tightens import restrictions, leaving Kazakh goods destined for China sitting idle.

Rail freight backed up at the Dostyk and Altynkol border crossings reportedly totals more than 7,000 wagons, some of which have been waiting for up to 42 days. Freight delays started in October, with agricultural exporters hit hardest, as grain and oilseed products can spoil if not delivered on time. Freight forwarders are also exposed to losses as they fear fines from their Chinese-side buyers for failure to deliver, leading to calls for the Kazakhstan Ministry of Industry and Infrastructure Development to issue force majeure notices for Kazakh exporters.

In 2016, a Strategic Cooperation Agreement and a Freight Forwarding Services Agreement were signed between the Kazakhstan national railway state-owned enterprise KTZ (Kazakhstan Temir Zholy) and the Urumqi Railway Bureau, now the China Railway Urumqi Group. The agreements allow for the passage of 18 trains per day. This was followed the year after with a KTZ and Russian Railways Strategic Cooperation Agreement. But it is the China side that is forcing the present slowdown by restricting imports into China under the guise of pandemic quarantine controls.

Changes between Kazakhstan-China cross-border trade as a direct result of the 2020 pandemic included suspension of non-scheduled CR-Express China-Europe rail freight, but not a reduction in the total number of cross-border trains. This had little effect on the China-Europe container trains, as the overwhelming majority of these train crossings are scheduled, but did provide an institutional grounds on which to restrict Kazakhstan’s exports to China.

Kazakhstan’s unilateral trade restrictions imposed due to the pandemic included unilateral bans on exports of most wheat and processed wheat and rye products, buckwheat, sugar, potatoes, and sunflower seeds and oil. The Eurasian Economic Union also imposed export restrictions on a similar array of cereal grains and basic foods including crushed and uncrushed soybeans, a strategic import for China.

But since July 1, Kazakhstan has been reopening its border crossings, without reciprocation from the Chinese side. In addition to Altynkol (Khorgos) and Dostyk (Alashankou), Kazakhstan has reopened the minor road border crossings of Kalzhat and Maikapshagai, but the border stations on the China side remain closed. In October, Kazakh railway wagons began backing up on the border, but new China pandemic restrictions since November 15 further reduced rail traffic to a maximum of 10-11 trains per day, with lows of six to seven per day. Zhanibek Tayzhanov, deputy chairman of the transport committee of Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Industry and Infrastructure Development asked China to reinstate the 18 trains per day benchmark but instead an agreement in late December only increased the daily limit to 15-16 trains. The main bottleneck is on non-containerized freight wagons, mostly acutely affecting agricultural commodities.

This means the freight backlog will begin to ease but will remain a problem. Kursiv reports Kanat Kobesov, deputy general director of KTZ-Freight Transportation LLP saying that the backlog of rail wagons fell from 9,000 to 7,000 through December, with the Kazakh side prioritizing perishable agricultural commodities and goods. The Kazakh grain exporter Food Contract Corporation reportedly sent 438 rail wagons to the border in October, with only 60 wagons crossing by December. Shokan Badykhan, executive director of the Grain Union of Kazakhstan, has said the problem is expected to continue throughout the first quarter of 2021.

Such a bottleneck at the border naturally creates a backlog farther down the logistics chain, Kursiv reported Yevgeny Karabanov, founder of the Severnoye Zerno Group, as telling a public online forum for representatives of the National Chamber of Entrepreneurs of Kazakhstan (Atameken) on December 22 that his company had 17 rail wagons bound for Dostyk sitting idle at Nur-Sultan or Akkol.

Trucks attempting to cross at the Nur Zholy/Khorgos road crossing have also faced delays. Where previously 100-150 automobiles were passing per day, the China side of the checkpoint is now only accepting 20-30 per day. The backlog of truck drivers sleeping in their vehicles has resulted in intervention by the Kazakh central government against extortion of truck drivers by local customs authorities. Kazakhstan’s new contactless electronic queue system for Nur Zholy has also added to the problem, amid widespread allegations from freight haulers of corruption, as some in the queue are seemingly bypassing others.

Number of in- and outbound rail wagons 2019-2020, China.

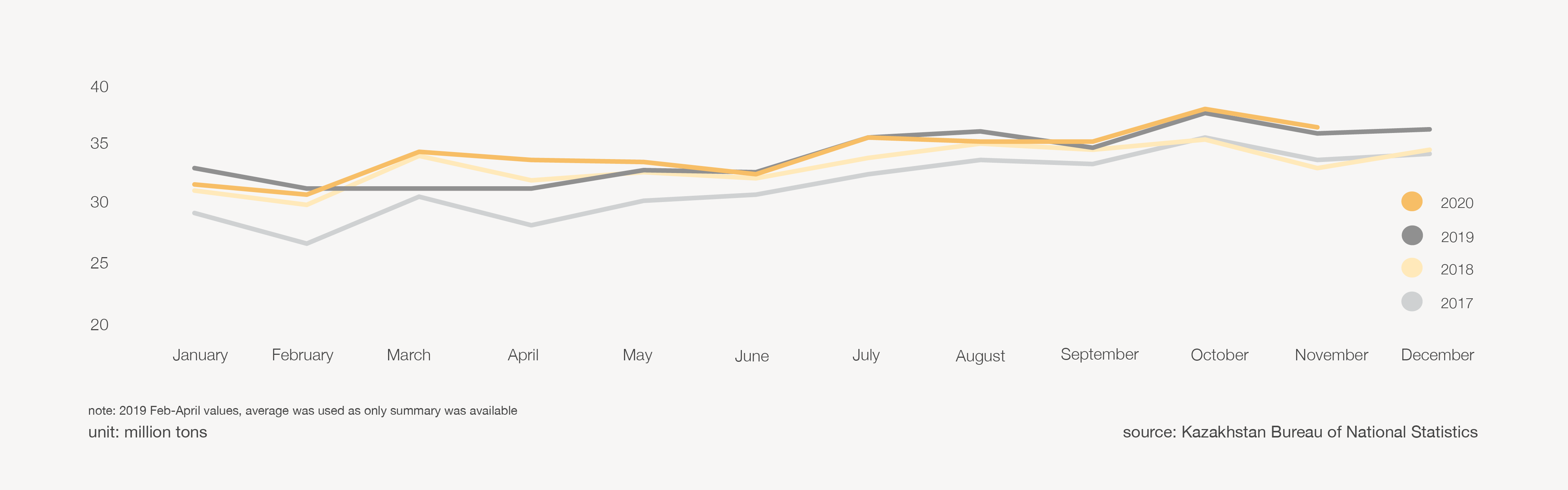

Monthly data on all goods transported by rail 2017-2020 in million tons, Kazakhstan.

Cross-border statistics for 2020 do not support China’s claim that the new restrictions are due to the pandemic. While all other forms of China trade transport fell in 2020 due to the pandemic, rail remained mostly steady throughout the year. Over the past decade, the monthly average rail trade between Kazakhstan and China measured in million of tons moved from around the low 20s in 2008-2011 to the mid 30s in 2017-2020, with no significant reduction in 2020 as a result of either the pandemic or any political issue, until now. Monthly customs data underlines the impact of the policy that China has implemented on rail imports: in November 2020, 16.7 percent fewer rail wagons crossed all of China borders than the same month in 2019.

For Kazakhstan to issue force majeure notices would be to accept that COVID-19 is genuinely disrupting supply chains. Trade and transport data from both China and Kazakhstan show that this freight connection should be functioning normally. Statistics show no major changes in rail freight transport between Kazakhstan and China through the pandemic year. This means that China’s actions are more easily analyzable as a classic non-tariff barrier to trade problem. Without central political malice, this seems like subnational bureaucratic incompetence on the part of China.

The National Chamber of Entrepreneurs of Kazakhstan (Atameken) has been the most vocal in calling for government action to resolve the freight bottlenecks. A coalition of freight forwarders and exporters joined the Transport Committee of the Ministry of Industry and Infrastructure Development on a December 24 trip to the Dosytk/Alashankou border crossing station. The state-market field trip included Atameken, KTZ and other logistics companies, the Kazlogistics Union of Transport Workers, and the Grain Union of Kazakhstan.

In mid-December, Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs sent a note to the Chinese Embassy in Nur-Sultan concerning the border issue. And a weekly subnational inter-governmental dialogue on rail freight each Tuesday remains in place. Kazakh Minister of Trade and Integration Bakhyt Sultanov said that China now has a similar problems with its other land border trading partners, including with Kyrgyzstan, Russia, and Mongolia. However Sultanov also said that the situation highlights the dangers of trade-reliance on China. Kazakh Prime Minister Askar Mamin, who was president of KTZ from 2008 until 2016, is currently in negotiations with the Chinese side to resolve the issue.

These China import bottlenecks call into question the viability of some of the wider aspects of Belt and Road Eurasian transport corridor integration, particularly the Middle Corridor connection to Turkey. From July 2020, a regular service between Xi’an China and Turkey using the Middle Corridor and Baku-Tbilisi-Kars rail infrastructure was formalized. The grander visions of Iran, Turkey, and Pakistan being connected by rail to China seem rather distant if the simpler bilateral Kazakhstan-China freight system is bottlenecking.

For Belt and Road economies which envisioned the shifting of the regional trade paradigm from land-locked to “land-connected” or “land-linked,” this bottleneck demonstrates that China is no more reliable a trade partner than Russia. Without any policy communication or political explanation, Kazakhstan’s exporters and freight forwarders are under pressure due to the actions of the Chinese state. For the European Union economies connected to the Iron Silk Road, the situation again demonstrates the lack of transparency in agreement documents and customs statistics. The Kazakhstan-China intercontinental rail system has taken on the institutional forms of the governance models of the states that run it.

Tristan Kenderdine is research director at Future Risk; Péter Bucsky is Ph.D. candidate at the University of Pécs, Doctoral School of Earth Sciences.