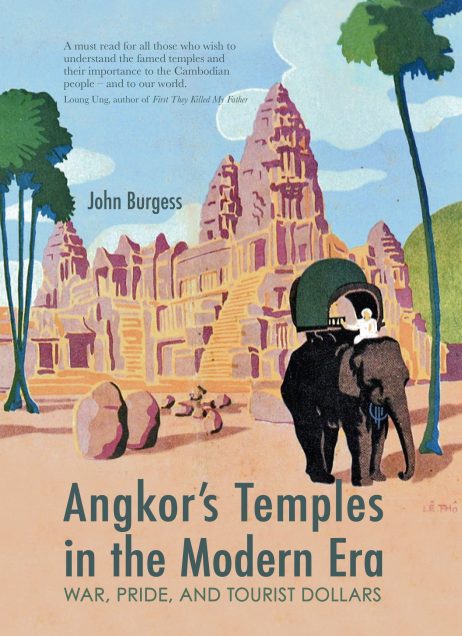

Despite being built centuries ago, the temples of Angkor are central to the history of modern Cambodia. A silhouette of Angkor Wat has appeared on the flag of every post-independence Cambodian regime, including the murderous Khmer Rouge, who otherwise waged war on every vestige of Cambodia’s premodern past. In a new book, “Angkor’s Temples in the Modern Era: War, Pride and Tourist Dollars” John Burgess details the temples’ tumultuous journey through the modern era, from the dawn of French imperialism through the abyss of war and genocide, to the mass tourism of the present day.

Burgess, the author of several books about Cambodia’s ethereal Angkorian monuments, spoke with The Diplomat about the temples’ role in the modern world – as colonial project, tourist attraction, and nationalist symbol – and their continuing grip on the imagination of Cambodians and foreigners alike.

Your book begins around the time of the temple’s “discovery” by the French explorer Henri Mouhot in the mid-19th century, and the extension of a French protectorate over the Cambodian kingdom in 1863. How were these temples initially seen by Western audiences, as news of their “discovery” tricked out? For the French, how did the discovery and documentation of the Angkorian sites shape perceptions of the Cambodia of the time?

The initial accounts — Mouhot’s journal, in particular — caused great excitement in France. With sketches and soaring prose, he described relics of a glorious lost civilization, waiting in the grip of tropical foliage for their secrets to be unlocked. Notions of Western superiority were on display in the first stabs at identifying Angkor’s builders. Alexander the Great and a lost tribe of Israel were proposed, as were Brahmin warriors who had come from India. For a long time, Westerners were not willing to believe that Angkor was the work of the forebears of present-day Cambodians.

The Louis Delaporte mission in 1873 brought back to France the first large-scale samples of Khmer sculpture and architectural elements. Over the years, through films, books, and Angkor-themed household bric-a-brac, the temples entered the consciousness of much of the French population, with a Western “orientalist” interpretation. The culmination was an expo in Paris in 1931 that included a full-scale replica of the upper tier of Angkor Wat.

Angkor Wat has been a touchstone for modern Cambodia, and an image of the temple has appeared on the flag of every post-independence Cambodian regime, including the murderous Khmer Rouge. What role did Angkor Wat play in the French attempt to fashion a national past for Cambodia? How have the Angkor temples figured in to the development of modern Cambodian nationalism?

Angkor was of course never “lost” to the Cambodians. They always knew it was there and probably thousands of them were living and farming among the temples when the first French were guided there by, who else, Cambodians. The largest temple, Angkor Wat, seems never to have been abandoned, with large numbers of monks present there in a monastery when the French arrived.

But at that point, Cambodians did not see Angkor as the heart of their nation. That was a notion later cultivated by the French. They made Angkor central to their narrative justifying colonial control — that Cambodia was a great kingdom fallen into “decadence,” and that France was setting it straight, bringing it into the modern age, by creating such institutions as ports and post offices, and by conserving — for Cambodia and the world — the fabulous archaeological site of Angkor. Angkor became the national symbol, appearing on the colonial flag, on banknotes, and postage stamps.

Angkor was central to a tame kind of nationalism that the French were trying to foster: the people of Cambodia would be proud subjects of the kingdom, yet at the same time proud subjects of France. Young Cambodians were brought to Angkor for work camp-type projects at temples undergoing restoration, in hopes that hefting the ancient stones would instill this approved kind of patriotism and reverence for the past.

In the 20th century, more genuine kinds of Cambodian nationalism began to emerge, foreseeing independence from France. Whether religious, revolutionary, or royal, these movements kept Angkor as their symbol of national greatness. The journal that is widely regarded as the first voice of true Cambodian nationalism had the title Nagaravatta — Angkor Wat. The French had succeeded in building pride in ways they never intended.

From the very moment that they were accessible, the otherworldly temples of Angkor have been a popular tourist destination. Describe the development of tourism under the French and thereafter. How did most early visitors experience the temples?

From the very moment that they were accessible, the otherworldly temples of Angkor have been a popular tourist destination. Describe the development of tourism under the French and thereafter. How did most early visitors experience the temples?

Tourism served two purposes for the French — to show foreign visitors world first-hand that Angkor was in goods hands, and to generate (they hoped) enough foreign exchange to make a difference in economic development. The French only gained control of Angkor in 1907 (it had been in Siamese hands) and it’s remarkable how quickly formal tourism began after that. In 1909, a small wooden hotel that would become known as the Bungalow was built opposite Angkor Wat’s entrance. That same year it was possible to travel to Angkor from Phnom Penh by steamboat on a package tour. Tourists were deposited at the mouth of the Siem Reap River, then continued upstream to Siem Reap town by pirogue or oxcart and then on the Bungalow. The École française d’Extrême-Orient, the French institute in charge of Angkor, carried out archaeology and restoration but also kept temples clear of vegetation for visitors and published guidebooks.

By the late 1920s, it was possible for tourists to fly to Angkor — on four-seat, open-cockpit seaplanes that set down very noisily in Angkor Wat’s moat. International tourism was a rich person’s game back then, and the numbers remained small — official figures show just 999 coming in the first six months of 1931, for instance. But it attracted some big names, including Charlie Chaplin in 1936. The French spent heavily to build the equivalent of a five-star hotel, the Grand (today the Raffles), which opened in 1932 as did the Siem Reap airport. All in all, these efforts were enjoying modest and gradually increasing success when World War II arrived and basically shut the trade down.

Sadly, an important running theme in the modern history of the Angkor temples is looting of statues and antiquities and their sale on the world market. This issue has been back in the news recently, since the passing of the controversial art dealer Douglas Latchford, and the news that his daughter will return some $50 million worth of stolen Cambodian antiquities. Can you describe how Cambodia’s endemic conflicts affected the temples and their preservation?

I’m sometimes asked how much damage the temples suffered during the war that lasted from 1970 to the 1990s. The answer is very little from bombs and bullets. The U.S. Air Force never bombed Angkor. The most serious incident of the 1970-75 war seems to have several shells from Lon Nol artillery that hit Angkor Wat one evening in 1971, killing two people and damaging a bas relief gallery.

The real damage of war was caused by two other things — art theft and neglect.

Theft had been a problem at Angkor basically from the start of the French era — indeed Delaporte’s bringing pieces back to France can be seen, for some of them, as government-sanctioned theft. He had pledged to the local Siamese lord not to take things. When tourism began, all visitors seemed to want a souvenir. To reduce the incentive for pocketing something when the guide wasn’t looking, the French began selling small ancient items that their experts deemed to be of no interest.

During the war years, theft reached astounding heights in the general chaos and lawlessness that reigned. It picked up again with the demise of the Khmer Rouge. I was in Angkor in 1980 as a journalist and saw newly beheaded sculptures. The trade continued largely unchecked for years. As a result, most every free-standing piece of sculpture that you see at Angkor now is a replica, because the original disappeared long ago or has been taken to safekeeping storage.

But there’s good news on art theft these days. Thieves are now generally limited to small, remote sites. They no longer plunder the main monuments. And through a combination of lawsuits, shaming, and diplomatic pressure, Cambodia has secured the return of major pieces from Western hands.

The other big impact of the war was neglect. Bernard-Philippe Groslier, the last French conservator, once said that Angkor was like a patient in a hospital, needing constant care. It got basically none for close to a quarter century, as it changed hands repeatedly and was essentially off limits to the outside world. Flights of bats moved back into tower chambers, grass and trees resumed their growth in the cracks between stones. The international conservation groups that came back in the ‘90s had their job cut out just to get the place back to where it had been.

In the mid-1970s, Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge regime pledged to eradicate outmoded tradition and return Cambodia to a new Year Zero, but strangely, except for some damage caused by the civil war, Angkor Wat survived. How did the Khmer Rouge see Angkor Wat? What did it symbolize for the regime, and was this any different from previous governments?

The Khmer Rouge razed or repurposed countless Buddhist temples in the country as part of their drive to destroy religion. Yet they did not do that to Angkor temples, nor do they seem to have engaged in major trafficking in artwork. They basically let Angkor be, though with virtually no maintenance. Their ideology was very Cambodian in viewing Angkor as proof of the greatness of the Khmer people, who would go on to even more glorious accomplishments under Khmer Rouge rule. So Angkor turned up in the speeches of Khmer Rouge leaders. Hanging on the walls of many Khmer Rouge offices were pictures of Angkor, not as decoration, but as political statement. And of course Angkor was on the Khmer Rouge flag.

The Khmer Rouge took the same pride in showing Angkor to foreign visitors that every government before them had — and every one after them has. The few foreign leaders who visited Khmer Rouge Cambodia were taken there — Ne Win of Burma and Nicolae Ceausescu of Romania among them.

Since the end of Cambodia’s civil war in the late 1990s, Angkor Wat has become an established stop on the tourism trail in Southeast Asia. Indeed, in 2019, the year before the COVID-19 pandemic brought global tourism to a halt, the temples welcomed 2.2 million foreign visitors. What problems have Angkor Wat and its surrounding monuments faced in an era of mass tourism? What is your outlook for the future?

Since the reopening in the 1990s, Angkor has faced the often conflicting needs of conservation and tourism. Yes, Cambodians from all levels of society are deeply proud of Angkor and want to protect it and show it off. Many also want to make money from it, whether in the form of a guide’s daily fee or quarterly return on a new resort. It’s hardly surprising, given that tourism is one of this very poor country’s few sources of foreign exchange. And while foreigners may gag at the noise and diesel fumes that come with high-volume tourism, to many Cambodians they’re welcome signs of prosperity. But given the country’s long history of corruption, that prosperity has hardly been shared equally.

It’s a fact that too many sets of tourist feet climbing a temple’s stone steps wear down that stone and undermine spiritual and architectural dignity. Angkor Wat at sunrise is a prime example of this kind of overload.

The people of Siem Reap have suffered severe pain this past year. Dreams of a new house, a new education, have evaporated with tourism’s sudden halt. I’ve wondered if a silver lining might be time to rethink tourism as it starts again, to make it more sustainable. Would there be ways to, say, spread the crowds out, direct more people to Cambodia’s many other attractions, and rope off more space inside the temples? It’s been good to learn that during the lull Siem Reap is getting some long overdue work on its streets and sidewalks. Cambodia would also do well to find ways to share the benefits of tourism more equitably among its people.