In the early morning of February 1, Myanmar’s de facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi and many of her cabinet members, along with student leaders, monks, bloggers, writers, and dissidents, were detained by the country’s military in an aggressive response to allegations of voter fraud in last year’s November election.

The election was undisputedly won in a landslide by the National League for Democracy (NLD), according to independent observers. The military coup has thus alarmed and angered many residents in Myanmar, from citizens to ex-pats.

“As a Myanmar citizen, I grew up under the military junta for years and I don’t want to go back to that dark era again,” Aung U Nu told The Diplomat. “We must not go back there for the sake of our future generations.”

Aung U Nu is a local journalist working for a prominent news publication in Yangon; he requested that this article avoid using his real name lest he face reprisals from the military.

“I’m shocked, disappointed and feeling very helpless as a foreigner because I have witnessed huge progress in the last five years with the country opening to the world,” said Irish national Kelly O’Connor (another pseudonym) over the phone. She has worked in Myanmar for eight years.

This sentiment has also been expressed in the chorus of condemnation from many of the world’s leaders.

On February 11, U.S. President Joe Biden denounced the Myanmar military for “rejecting the will of the people” and “undermining the country’s democratic transition and rule of law.” He issued an executive order hitting members of the junta with sanctions.

Jacinda Ardern, the prime minister of New Zealand, stated on February 9 that her government will be suspending all high-level political and military contact with Myanmar and that a travel ban for Myanmar’s military officials will be soon put into place.

A statement released on February 5 by members of the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights called on Myanmar’s military leaders for a “democratic and peaceful outcome that is in accordance with the will and interests of the people of Myanmar.”

ASEAN leaders have also called for a special meeting on Myanmar and reminded the military to adhere to “the rule of law, good governance and the principles of democracy and constitutional government, as well as the promotion and protection of human rights and respect for fundamental freedoms.”

Many observers have pointed fingers at the Chinese and Russian governments for backing the junta and blocking the U.N. Security Council from denouncing the coup. In a widely criticized headline, the Chinese state media outlet Xinhua labelled the military takeover a “major cabinet reshuffle,” a statement that would have angered Aung San Suu Kyi’s supporters.

For the moment, the mood on the ground in Myanmar remains tense. As demonstrations gather strength, the world is watching to see what further indignities the military might unleash on the country’s 54 million people, which have now been thrown into limbo.

Reactions From Yangon

This week, The Diplomat spoke with both expats and locals living in Yangon to gauge their reactions to the coup. Due to safety concerns, they all wished to remain anonymous and have been given pseudonyms.

“I think with the initial shock starting to wear off, people are now quite angry and frustrated,” said O’Connor. “It has happened before. A lot of people here lived through previous coups and none of them has gone well, every coup that has happened has been violent. Outside of protesting, people are finding other ways to show their rejection of the coup through social media.”

O’Connor went on to mention that residents are afraid of the military’s might and assume that if soldiers go onto the streets to combat the protestors then only bloodshed will ensue.

On February 9, nationwide curfew orders were rolled out to quell pro-democracy demonstrations during the hours of 8 p.m. and 4 a.m. In the capital, Naypyidaw, seven people were injured and two remain critical condition after a protest turned violent there, with the police firing water cannons and even live ammunition at the crowd.

In the evenings before the curfew, people had been staying at home due to coronavirus health concerns. Many were honking their car horns on the streets or banging pots and pans in their neighborhoods as a way to protest the coup.

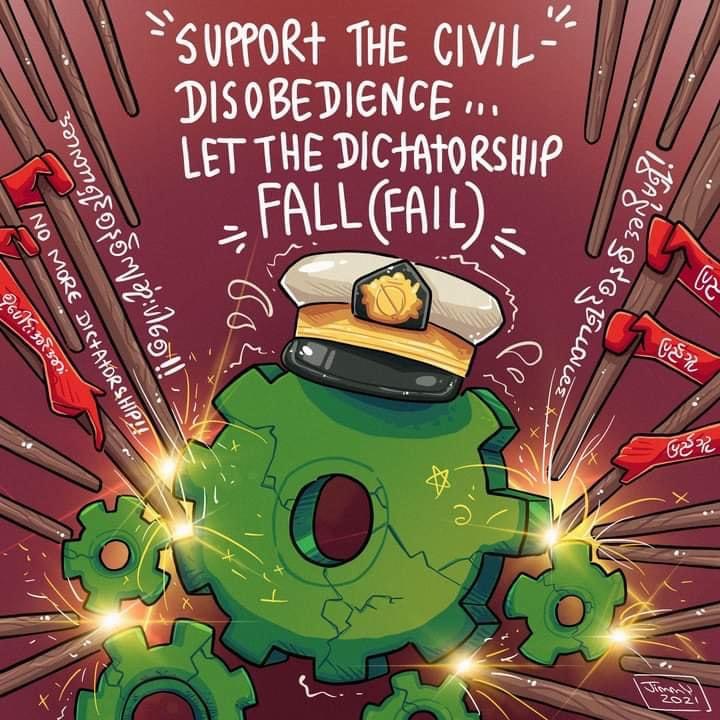

Dissidents and activists created the Civil Disobedience Movement as a way for citizens to voice their rejection of the new military takeover. The movement is being initiated by medical workers who are currently on strike to protest the coup and who are also now urging NLD supporters to demonstrate.

An animated graphic promoting the civil disobedience campaign, shared by an anonymous source.

The NLD has been widely lauded for its implementation of proper health protocols for the country’s citizens during the COVID-19 pandemic. Inside Myanmar, people have praised the NLD for lifting the quality of life for most of its citizens; however, the NLD’s treatment of the Rohingya minority has been widely castigated by the international community.

“Health care workers were the first people to refuse to go to work for the military by being a part of the new civil disobedience campaign, which was an interesting twist of events,” said O’Connor.

In Myanmar’s past, it has often been the Buddhist monks who have spearheaded protests against the military. The fact that the monks haven’t been as vocal in this latest standoff suggests that they are possibly either too afraid to speak out or some may have given their sympathies to the military.

Myanmar’s netizens today have better access to the internet, along with apps such as Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) and other platforms to communicate with the international community, allowing them to circumvent recent blocking of phone lines and bans on social media apps by the military. Many citizens who can afford it have rushed to purchase VPNs in the past week to gain full access to the internet.

It is thought that many members of the government and even the military themselves mainly rely on Facebook’s Messenger app to communicate. Many citizens are deeply concerned that if the local media gets silenced along with more internet blackouts, the country could take a further turn for the worse.

A coup “is the worst outcome for this country, the military must respect the fairness of this recent election result and they must release the people they have arrested,” said Aung U Nu, the Yangon-based journalist.

The military announced that they will hold onto power in a one-year state of emergency and that they will conduct another election following that. As of now, many residents feel that any prior trust between the people and the military has since been shattered and many fear that the new election is simply a way for the military to reconsolidate their power.

Beyond all this, there is an overall sense that the majority of Myanmar’s people are hoping that the new Biden administration in the U.S. will do more than just enforce more economic sanctions on the junta’s wealthy generals, who are already well-versed in withstanding overseas pressure.

In previous years, sanctions have only served to harm average civilians in Myanmar, who are currently suffering from both a health and economic crisis due to the pandemic. “Even before the NLD, the country’s economy was on the way up and now this coup has struck after COVID-19,” O’Connor said, worrying about the potential damage economic turmoil could do to the average person.

It is difficult to make predictions on what could happen inside Myanmar in this next period, aside from the possibility of more international investors pulling out of the country and ongoing protests turning violent. Outside of the major superpowers of China, Russia, and the U.S., Japan, India, Bangladesh, and Singapore all have important political and economic ties with Myanmar and they could play a vital role in helping to deescalate the current tensions. By initiating an authentic and meaningful dialogue with the military, there is some hope that the country will return to some form of stability. The next few weeks will be critical.

Hugh Bohane is a freelance journalist who has covered Asia for over 10 years. He has contributed to The Diplomat, ABC, Euronews, New Internationalist and other esteemed press.