Writing about Pakistan-U.S. relations is like composing a piece of literary criticism of Shakespeare’s “Hamlet,” always looking for new answers to old nagging questions, and falling short. Nevertheless, a serious inquiry into the history of the bilateral relationship may help our quest for answers. The fact is that the history of Pakistan-U.S. relations is much misunderstood.

At present, Pakistan-U.S. relations are very much on Islamabad’s mind as it increasingly fears being caught in the crossfire between the United States and China, while having to cope with the impact of deepening India-U.S. relations, already reaffirmed by the Biden administration, and the looming crisis of potential civil conflict in Afghanistan following an American withdrawal.

Yet there is also Pakistan’s hope for a U.S. role in the improvement of India-Pakistan relations and for the revival of ties with Washington. Those hopes may have partly inspired the Kashmir ceasefire deal and the peace overtures pitched by the leadership at the recent Islamabad Security Dialogue. And now comes a deal between Iran and China, opening up the possibility that the United States has lost Iran to China and may not like Pakistan to be swept away into Beijing’s strategic orbit, too. These may arguably be the worst of times, and the best of times, for Islamabad.

Probing the history of Pakistan-U.S. relations will not resolve Pakistan’s policy dilemmas or realize its hopes. But it may help to understand the reality of shifting U.S. interests in the region and why Pakistan has sometimes been important and sometimes not, and what to expect from Washington, and what not to expect, as the Biden administration concludes its review of foreign policy, including the relationship with Pakistan.

Neither Strategic Nor Transactional

As Richard Armitage, then-deputy secretary of state, admitted in 2002, Pakistan was never important to the United States in its own right. It was important, he said, because of third parties. The implication was that Pakistan had no permanent value for the U.S., and its importance for Washington derived from the importance of South Asia more broadly.

South Asia’s importance for Washington until the end of the Cold War was limited and variable. Now the region is far more relevant to the United States for geopolitical, national security, and economic reasons. This requires Washington to invest in wider and longer term regional engagement in which both India and Pakistan have a place. But that place it is not next to each other. While India occupies a strategic space, Pakistan has been on shifting sand.

If the U.S. cannot have a strategic relationship with Pakistan, has the relationship been transactional then? Yes and no. It was transactional, but dealing with strategic issues. And even the transactional relationship has not been working well because of contradictions within it and between each side’s relationships with other countries.

Paradoxes in the Pakistan-U.S. relationship are not new. They have existed since the very beginning and lie at the heart of misperceptions about the relationship. The two countries have had very high profile relations from time to time, even bearing characteristics of close allies. And yet Pakistan suffered frequent sanctions reserved for adversaries. Periodically the U.S. leadership has praised Pakistan sky high as an ally. Yet Islamabad has also been maligned by Washington. This is all the more puzzling considering that the Pakistan-U.S. relationship has historically served some of the critical national interests of the two countries and may do so again.

A Very “Special” Relationship

In their first engagement during the early years of the Cold War Pakistan had important symbolic value as an ally both as the then-largest Muslim country with a salient geopolitical location, and as a link in the U.S. chain of alliances from Europe to the Middle East to Asia in the Cold War’s containment policy.

During each phase of their relationship thereafter — during the 1980s against the Soviets in Afghanistan and their post-9/11 engagement — the specific task given to Islamabad by Washington was critically important not only in foreign policy terms, but also politically in U.S. domestic politics.

As a result, the relationship came to have two unusual attributes. Pakistan was handled by successive administrations in the United States in ways that were far out of proportion to the country’s normal importance. Given the impact on domestic politics and nature of the relationship — most of the dealings with Pakistan related to military and intelligence cooperation — the White House was driving ties.

Secondly, focusing as it did on intelligence and military cooperation, much of the relationship with Pakistan came to have an “underworld” aspect that was beyond public view. Meanwhile, on the surface in the U.S., Pakistan’s importance was not so evident. That presented a recurring challenge for U.S. administrations to orchestrate domestic political support for Pakistan, particularly as the country also embodied some negative features.

To this end successive U.S. administrations exaggerated Pakistan’s geopolitical importance and its role as an ally and discounted the negative sides. Similarly, the Pakistani establishment — specially a military government — sexed up the relationship to broaden public support for it and blunt its own unpopularity.

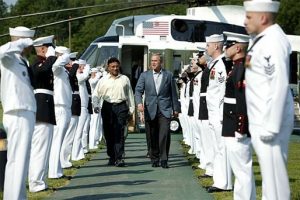

The United States made its own efforts to build public support for the military governments, which were providing help that a democratic and nationalist government in Pakistan would not. President Richard Nixon called Pakistan the United States’ “most allied ally” and announced that relations with Pakistan were a cornerstone of U.S. foreign policy. President Ronald Reagan and Secretary of State George Shultz eulogized Pakistan as a front-line state, praising President Zia ul Haq highly. President George W. Bush cozied up to President Pervez Musharraf by saying he could do business with him.

All of this created serious problems. When the special need that had brought the two countries close was fulfilled, and the relationship returned to normal the U.S. side found Pakistan falling far short of its inflated image as an ally. Pakistan’s conduct came under heavy scrutiny across the board in media and Congress. And there were cries of betrayal.

There were equally strong charges of betrayal by Pakistanis. Most Pakistanis, like most foreigners, have little understanding of the formation of public policy in the United States and did not realize the American leadership’s laudatory remarks were political statements, not policy statements. They came to think of the inflated relationship with the U.S. as the natural default position, not an exaggerated position of convenience. They were then outraged when the U.S. imposed various sanctions on Pakistan, in the lull between moments of necessity in the alliance. Pakistanis strongly believed their help to the U.S. had an enormous importance, especially in the Afghanistan war of the 1980s and the war on terrorism. They feel that after 9/11 they not only gave help but also suffered horrifically from the consequences of the war in Afghanistan.

A Changed South Asia

Where do we go from here? South Asia has changed and so has the way big powers relate to it. After one of the worst periods in the history of the relations recently, owing largely to the troubled Afghanistan war and the rising tide of India-U.S. relations, Pakistan-U.S. ties might see some stability and new meaning in the steadying hands of Biden. The United States may now be looking at the relationship as part of its broader interests in South Asia, which are geopolitical, regional, and security related. Some interests will be served by India, while others served better by Pakistan. These two relationships now serve different U.S. purposes, some of which conflict, and some overlap. To maximize the benefits from both the relationships, especially from the arguably more important matters with India, Washington will steer clear of India-Pakistan disputes, except for crisis management.

Pakistan needs to learn from its misunderstood history of relations and adjust according to the vastly changed times. Because of intensifying competition between the U.S. and China, Pakistan’s geopolitical location and close ties with China can work both as an asset and a liability. It depends on what Pakistan makes of it. Washington cannot leave Islamabad entirely dependent on China and useful only to Beijing’s strategic purposes. But in order to be useful to both the U.S. and China, Pakistan has to build internal strength, raise its contribution to peace efforts in region, help stabilize Afghanistan, and enhance its potential as an economic partner. Ultimately what is good for Pakistan will be good for Pakistan-U.S. relations.

Finally, Pakistan should scale down its expectations of the U.S. and try to lower Washington’s expectations for Islamabad. It should treat the relationship with the U.S. as necessary, but not critical.