In November 2020, immediately before the U.S. presidential election, we conducted a public opinion survey in China to explore Chinese citizens’ views on 14 developed countries, including the United States. The survey was inspired by and complements a Pew Research survey that looked at public opinions about China in these 14 countries. Importantly, we found that the Chinese and Americans disliked each other to a similar extent, with 77 percent of Chinese respondents expressing very or somewhat unfavorable views of the United States. We proposed that much of the Chinese antipathy toward the U.S. stemmed from an unprecedented deterioration in the bilateral relationship during the Trump presidency.

Has Chinese public opinion changed with the arrival of a new U.S. president?

We conducted a second survey of 1,018 adults between January 25 and February 2, 2021, after Joe Biden was sworn into office, to investigate whether the Chinese public’s views toward the 14 countries, particular the United States, have changed since Trump left office. We asked the same question as in our pre-election survey: “What’s your view of the following countries?”

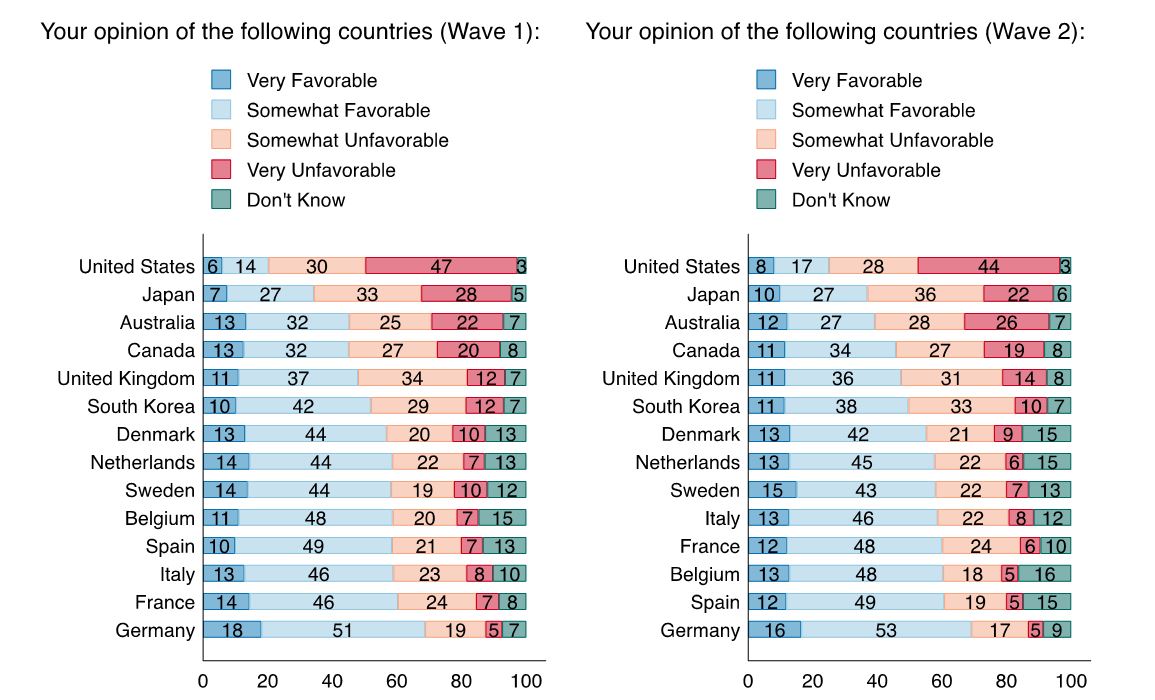

The results of the second survey are largely consistent with the first one. Specifically, the United States still tops the list for negative views held by the Chinese public, with 72 percent of respondents holding very or somewhat unfavorable views of the country, followed by close allies of the U.S.: Japan (58 percent), Australia (54 percent), Canada (46 percent), and the United Kingdom (45 percent). As in the first survey, continental European countries fared better, with Chinese negative views at or below 30 percent.

These patterns across the two surveys suggest that the underlying trends in Chinese public opinion were stable during those three months and will likely remain so in the foreseeable future. No single event, even a significant one such as the historic U.S. presidential election, can dramatically change the underlying sentiment.

However, there were small movements in Chinese public opinion across our two surveys that are worth noting.

First, the unfavorability toward the U.S. has dropped from 77 percent to 72 percent. The level of uncertainty – that is, the percentage of respondents who chose “don’t know” – is the same for the U.S. in both surveys, at 3 percent, so the change represents a 5 point increase in favorability. It appears that at least some Chinese animosity toward the U.S. might have been tied to the Trump presidency rather than the country itself. Consequently, the leadership change in the United States might have led to a small favorability bump across the two surveys.

Second, for close U.S. allies, while the unfavorability level was practically unchanged for Canada and the U.K. and dropped slightly for Japan, negative views of Australia rose from 47 percent to 54 percent, a 7 point increase. The change reflects a further deterioration in China-Australia relations. Shortly after our first survey, Beijing slapped new tariffs or restrictions on Australian exports of beef, wine, barley, timber, and other products. A Twitter-engendered spat between a Chinese diplomat and the Australian prime minister over war crimes committed by some Australian soldiers in Afghanistan also escalated into a full-blown war of words between the two countries, with additional countries weighing in. The news and analysis of these events were widely reported, discussed, and shared on social media in China, likely contributing to worsening views on Australia.

Third, Chinese views toward continental European countries have remained stable, with no increase in negative views and in some cases a slight decrease. Of note, Germany continues to lead in favorability, set apart from the rest of the pack by 9 points or more. In recent years, Germany has often criticized China’s policies in Xinjiang or Hong Kong, but it also led the signing of the “EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment” at the end of 2020, despite concerns raised by the then-incoming Biden administration. Evidently, with these balancing acts, Germany has managed to largely stay on the positive side of Chinese public opinion.

Data based on the authors’ survey. Figures have been rounded and may not add up to 100 percent.

In sum, the presidential election in the United States seems to have resulted in a small but positive shift in Chinese respondents’ perceptions of the United States. This may reflect the possibility that some Chinese animosity was tied to President Donald Trump. On the other hand, most Chinese are likely to remain cautious or even skeptical about what the new Biden administration will mean for the future of China-U.S. relations, given Biden’s widely reported plan to line up democratic allies to counter China. In addition, no specific policy announcement regarding China came out of Washington in the first week of the new presidency, leading up to our second survey, which might have contributed to the wait-and-see attitudes reflected in the survey.

Chinese public opinion can embolden or constrain China’s foreign policy. Chinese leaders, like their counterparts anywhere in the world, would most certainly prefer to enjoy public support of their foreign policies than otherwise, because such support strengthens regime stability and facilitates the mobilization of societal resources for important policy initiatives. This might be increasingly true in the age of social media, with nearly 1 billion internet users in China, a non-trivial portion of whom do not shy away from open and critical discussions on Chinese foreign policies and other countries’ China policies. For now, it is difficult to gauge the extent to which such discussions among the Chinese public can shape China’s foreign policies and influence domestic preferences for foreign products and services. But it would be unwise for anyone to ignore their voices.