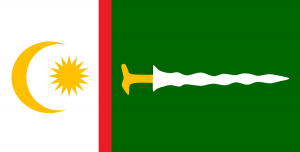

Two years into the creation of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM), the peace process that put an end to decades of war in the Southern Philippines may be running into a rough patch.

Leading the interim government, the former rebels of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) are making headway in building up the new entity’s institutions and passing key legislation ahead of the new region’s first elections, due in 2022, but delays resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic now threaten to push that important deadline. Another key element of the 2014 peace deal between the rebels and the Philippines government is also languishing: the so-called “normalization process,” an ambitious combination of measures that aim to demobilize Moro Muslim fighters, transform their camps into peaceful and productive communities, establish a transitional justice process, and carry out a series of confidence-building initiatives. This process was off to a relatively good start, but here again COVID-19 has considerably slowed the process down over the past year, raising the risks of frustration among ex-combatants and civilians alike.

In a historic moment, a third of the MILF’s estimated 40,000 combatants, who had been operating in the jungles of Mindanao for over four decades, laid down their arms in early 2020. But due to the pandemic, the next round of decommissioning has not moved beyond the planning stages. While discussions about how to fast-track the process are ongoing, a recent rise in COVID-19 cases in the Philippines is likely to complicate things further.

The ex-rebels are also growing impatient over the government’s failure to deliver promised socioeconomic packages to decommissioned combatants. These are supposed to include financial aid, agricultural support, housing, and other assistance for their transition to civilian life. While the government pledged a package amounting to one million Philippine Pesos per combatant, so far each ex-guerrilla has only received a lump sum of 100,000 pesos ($2,066). Failure to make headway on this issue could lead the MILF leadership to think twice about continuing with the disarmament roadmap.

Another challenge concerns the “camp transformation” agenda contemplated by the peace deal: a development roadmap intended to deliver peace gains for the Moro communities amongst which MILF combatants live. Some international donors have launched development projects in the six major MILF camps identified in the 2014 peace agreement as priority areas, but real peace dividends have yet to fully trickle down, as projects implemented to date have been rather small scale. Developed at the end of last year by the regional government, a more comprehensive camp transformation plan is now in place. But details still need to be ironed out between Manila and the MILF, and implementation promises to remain a challenge. Given pandemic-related spending, the Philippine government may not have sufficient resources to undertake this ambitious socioeconomic transformation in the coming months. Support from international donors will, in this respect, be crucial.

Other elements of normalization also lag. Crucial security measures foreseen by the peace deal, particularly the dissolution of private armies controlled by powerful clans and other power brokers across the Bangsamoro, remain a major challenge. The deployment in sensitive areas of joint peacekeeping teams made up of soldiers and ex-MILF combatants has also hit a series of hurdles at the local level. While the disbandment of private armed groups is largely a question of political will in Manila, the government and MILF need to determine a clear mandate for the peacekeeping teams if they are to be efficient, particularly regarding their capacity to use force.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been an unwelcome distraction for the Bangsamoro peace process, putting pressure on both Manila and the regional government to focus on immediate governance and public health issues, rather than confronting the challenges of the transition and normalization. There is now talk of extending the Bangsamoro transition period beyond 2022, when the first parliamentary elections were meant to elect the region’s autonomous government.

Though the normalization timetable is not technically tied to the elections, such a delay could lead officials to slow down the pace of these reforms as well – especially since, according to law, an extension would need to be for three years. While it seems unlikely the MILF leadership would call for a return to war, frustration at the pace of normalization could lead some of the group’s members to express their grievances through violence. Other militant groups active in the Bangsamoro could also endanger the nascent BARMM by blaming the MILF and Manila for slow implementation, recruiting disappointed Moro youth in the process. Just last month, fighting in Maguindanao province led to the displacement of tens of thousands of civilians, illustrating how volatile the situation on the ground remains.

President Duterte’s recent declaration of an amnesty for various Philippine rebel groups, including the MILF, was a welcome step toward reviving the normalization process and strengthening trust with the MILF amid the pandemic’s grip. But much remains to be done for the process to regain momentum at this crucial juncture. The national government should start by speeding up delivery of promised socioeconomic assistance to decommissioned combatants to reassure disgruntled ex-guerrillas that they will enjoy a peace dividend, and to signal to the MILF that it remains committed to the peace process. Moving ahead quickly with the plan to disband private armies is also crucial if to avoid the MILF decommissioning resulting in a security vacuum, which could lead to more conflict across the Bangsamoro.

For its part, the MILF should stick to the decommissioning roadmap as it was originally laid out, whether the transition is extended or not. Through their role in the regional administration, the ex-rebels should also work to strengthen local conflict resolution mechanisms to address often violent clan feuds that affect various parts of the region and could further jeopardize peace.

The international community, which has supported the peace process in the Bangsamoro ever since the peace agreement, has a crucial role to play at this moment of uncertainty. Donors can help things move in the right direction by contributing to the Bangsamoro Normalization Trust Fund, the dedicated funding mechanism created by the government and the MILF to finance relevant development projects. While initiatives focused on the six priority MILF camps are crucial, support should also flow to other conflict-affected areas. Uneven distribution of aid may well create tensions that could, in turn, stir further resentment and conflict.

The 2014 landmark peace agreement envisioned a comprehensive roadmap to peace that sought to tackle the complex causes of the Bangsamoro conflict in order to close the book on this war once and for all. To fulfil the Bangsamoro population’s expectations they raised as a result, Manila and the former rebels must not let the pandemic knock them off course after making such good progress towards a peaceful transition. Despite the hiccups, both urgently need to return to the spirit of cooperation that made this historic peace deal possible.