A campaign by the Chinese government to discredit survivors of detention camps who speak out against the regime has taken a macabre turn with the release of a “proof of death” video claiming that the demise of a young Uyghur woman was self-inflicted.

The short video set out to prove that Mihriay Erkin did not in fact die under interrogation as alluded to by Radio Free Asia. Instead it set out to “put the record straight” and claimed her death was caused by a refusal to accept treatment for the complications of Hepatitis B.

So-called “proof of life” videos, whereby long “disappeared” relatives of the diaspora are paraded on screen extolling the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), are the CCP’s latest tactic used to discredit activists campaigning on behalf of their families in Xinjiang. The loved ones deemed to have vanished appear onscreen against a plain background, or in the comfort of their own home around lavishly spread tables. They are usually filmed lambasting their exiled relative, telling them to stop criticizing China and demanding that they return. Very often work colleagues or friends are drafted in to cast doubt on the moral character of the exile as well, accusing them of loose living, lying, or theft.

The CCP has refined its modus operandi since the very first of these was released following the rumored death of a beloved Uyghur singer and musician, Abdurehim Heyit, in February 2019. Against a grey-tiled background, the disheveled Heyit, with a stubbled chin but a shaved head, reassured the world that he was alive and in “good health.”

Far from reassuring activists, the condition of Heyit and his awkward speech, which many fear was made under duress, provoked deep concern. It also unleashed the #MeTooUyghur campaign, with relatives clamoring for news of their own families.

These “proof-of-life” videos have developed in style and plausibility since the clumsiness of those early days. The CCP’s English-language mouthpieces, Global Times and China Daily, and broadcaster CGTN (China Global Television Network) have made a series of documentary-style features describing the new lives of exiles’ relatives, who have been “cured” from “extremism” and “separatist” tendencies during spells in the so-called Vocational Training Centers – more widely known abroad as reeducation camps.

A CGTN crew went to great lengths to follow up on a story released to Western media by exiled poet Aziz Isa Elkun, after he noticed on Google Earth that his village’s ancestral cemetery, together with his father’s well-tended grave, had been destroyed and his father’s remains removed. CGTN journalists traveled miles along dusty roads to the remote village where Elkun’s elderly widowed mother, whom he had not been in contact with or seen for three years, was forced to denounce her son and claim her husband’s new “eco” grave was more convenient.

Now, China appears to be moving in a gruesome new direction. When a “proof-of-life” video proved impossible, the CCP made a video attempting to absolve itself of responsibility in a detainee’s death.

The death of Mihriay Erkin has always puzzled her uncle, the Uyghur language educator and activist Abduweli Ayup, now living in Europe. Since her mysterious disappearance in June 2019 after she was pressured into returning to Xinjiang by her parents, despite having a promising career in biotechnology science in Japan, Ayup has left no stone unturned to discover her whereabouts. He was blocked at every turn.

Mihriay Erkin during her student days in Japan. Photo provided by Abduweli Ayup.

Only after investigations by an RFA reporter, who called the police station in her home town, was her death finally confirmed in June 2021. But Ayup was none the wiser as to the cause of her death or the reason for her disappearance.

The recent appearance of a private video describing how Mihriay Erkin died, however, has only increased his distress and given him more questions than answers.

The clip, released a full two years after Erkin’s disappearance, seems to have been concocted to rebut a New York Times expose in July this year on the treatment of exiled Uyghur activists’ relatives, who are often rounded up and sent to camps in retaliation. Erkin was one of the subjects of journalist Austin Ramzy, who had interviewed Ayup on the activism that might have contributed to his niece’s retaliatory arrest. Following his feature, Ramzy was sent a private video clip by the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region news department, in which Erkin’s doctor and younger brother testified that she had been the author of her own death.

These videos are intended to reassure the world that Beijing has the Uyghurs’ best interests at heart and to quell the “fake news” attacking China from the West. But the decision to depart from China’s usual policy of publicly countering attacks on its integrity on national and international television, instead sending a bespoke private video to an international journalist, seemed strange to Ayup.

“They were obviously expecting a retraction in the New York Times,” he said, adding there were too many flaws and inconsistencies in the video for it to be credible.

A screenshot of the preamble to the video.

The preamble sent in a separate document to Ramzy was full of factual errors, according to Ayup. The document claimed that the reason Erkin finished her studies and returned home was ill health. Nothing could have been further from the truth, said Ayup, who confirmed that she had in fact already graduated in 2017, two years before she was called back. He produced text message evidence from her last correspondence with a friend from the Tokyo airport, indicating a reluctance to return. Erkin told her friend that a sense of responsibility toward her ailing parents, who themselves had been threatened if they could not persuade her to come home, had forced her hand.

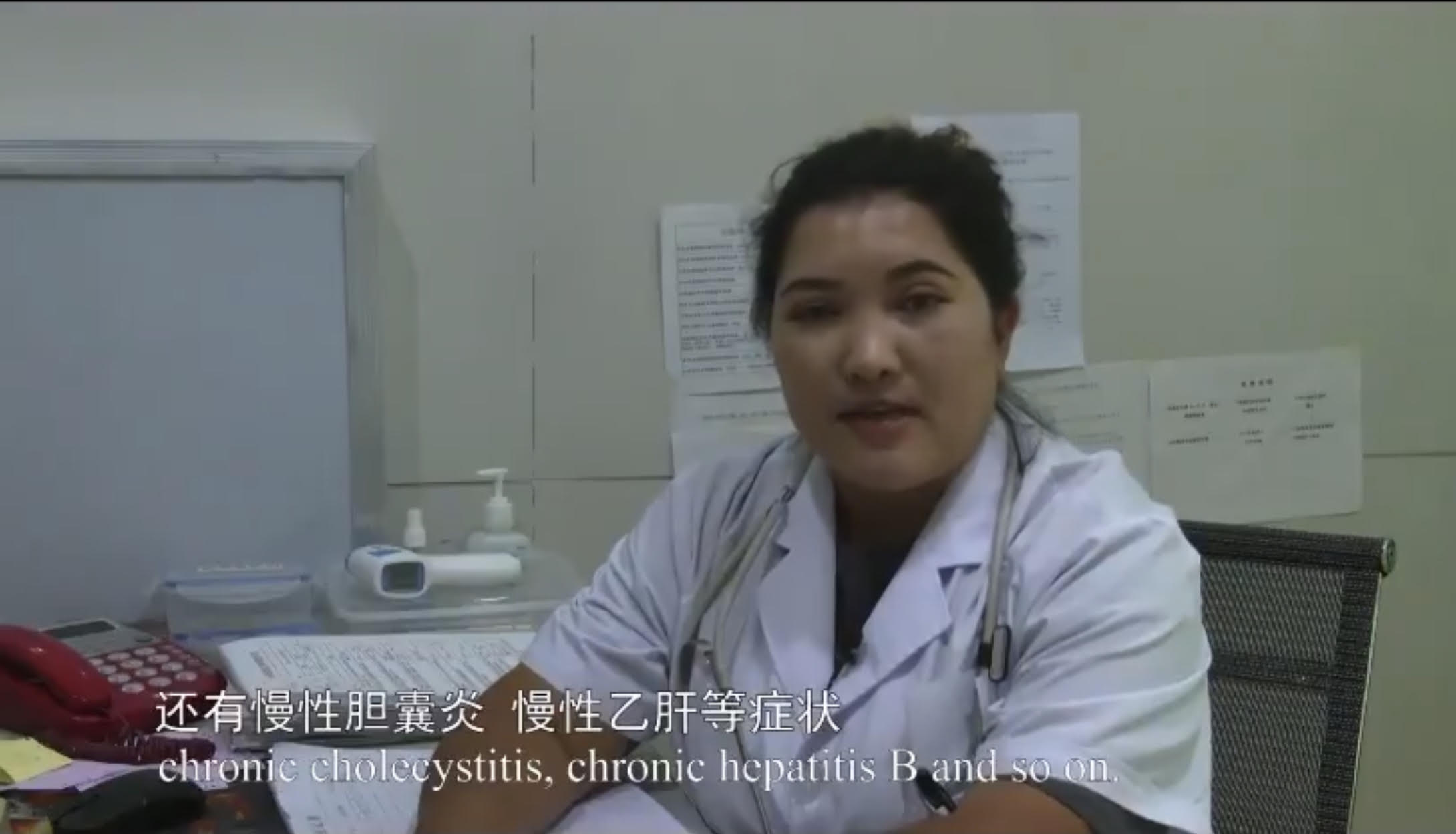

In the video, filmed on an unknown date and from an unknown location, one Dilare Mahmut, claiming to be Erkin’s “attending physician,” recited a list of conditions suffered by the young Uyghur, from which she eventually succumbed after refusing treatment.

Erkin was a fit and healthy 30-year-old before she disappeared, according to her uncle. After 18 months in detention, the doctor described Erkin as suffering from a raft of ailments: acute gastroenteritis, chronic cholecystitis, chronic hepatitis B, severe anemia, malnutrition, “pleural fluid on her left lung,” “abdominal fluid (ascites) caused by liver disease,” followed by “etc.” According to the video, Erkin was offered treatment for these conditions but had refused.

In this screenshot from the video, Dilare Mahmut, who claims to have been Erkin’s doctor, recites the lengthy list of her ailments.

She had rejected all food and drink, pulled out intravenous drips, and refused to cooperate with treatment, to the extent the hospital thought she might have a “depressive disorder.” According to the hospital, even her own family could not persuade her to cooperate and she eventually died of “multiple organ dysfunction syndrome.”

The elephant in the room for Ayup was not that his niece had been sick, but how she had become so ill. If in fact Erkin had died of Hepatitis B, and the video was genuine, Ayup argued, far from being a vindication of China, it was further proof of the injustices underway in Xinjiang. Hundreds and thousands of innocent people have been detained without trial; Erkin’s rapid deterioration, in Ayup’s eyes, demonstrates the squalid conditions in which these detainees are kept.

As far as Ayup was concerned, the video is evidence of the crimes the CCP is meting out on his people and the lengths it is prepared to go to cover its tracks. “There have been too many accounts of conditions in the concentration camps for it to be a coincidence that Mihriay had become undernourished,” he said. “Prisoners are fed on steamed buns, vegetable gruel, and two glasses of water a day. If the video is true, no wonder she had developed malnutrition.”

The account of Erkin’s multiple health problems was evidence to Ayup of his niece’s suffering during her final months of life.

“If in fact she refused medication and pulled out intravenous drips, we have to ask the question: why?” asked Ayup, who himself endured the terror of arrest, torture and incarceration some years ago for the “crime” of promoting the Uyghur language. He explained the terror that fills every inmate, as they are subjected to unknown drugs and tests, which many detainees assume are meant to determine their suitability for organ harvesting.

“I’ll tell you why. Everyone in those prisons assumes they are there to be killed. Why should she submit herself voluntarily to unknown drugs that could have hastened her own death?” he asked.

“It would not have been surprising either if she was depressed,” Ayup added, emphasizing that she had been inveigled home from a promising career in Japan to ostensibly care for ailing parents, but was in fact summarily arrested and detained on her arrival.

Erkin’s brother, Mirshat, appears in the video to refute the “rumors” around her death.

Commenting on Erkin’s brother’s performance on the video, Ayup noticed his script was striking in its similarity to that of the doctor. “I can only imagine the number of times he must have practiced those words,” said Ayup, cynically.

“Mirshat loved Mihriay. It would have been torture for him to blame his sister in this way for causing her own death. I can’t imagine what he went through.”

For Ayup, this video has only served to reinforce his determination to speak out about the atrocities against his people. “I dread to think what Mihriay suffered in detention,” he said.

“I am heartbroken, but will continue the fight.”