China’s governance is barely institutionalized into any formal central forms of political power. Instead, China is governed by geographic regions. There is no distinction between central and provincial positions once cadres reach the “provincial-ministerial” zhengbu rank. The central governance structure is then made up of a combination of formal institutionalized positions and loose alliances, making an informal centralized power structure close to a form of cadre-federalism.

Sub-provincial level cities, though, are governed by cadres at the fubu rank, half a rank above prefectural rank and half a rank below provincial. There are 15 proper sub-provincial level cities, plus two of the 19 centrally governed “New Areas” as well as the Ili Kazakh Autonomous Region, a sprawling far western Xinjiang administrative unit that covers Ili proper, Tacheng, and Altai prefectures. The proper sub-provincial level cities mostly cross-over with the state planning mechanism, with 13 of the 15 also directly named cities in the central state plan, the exceptions being Hangzhou and Jinan. Cadres who pass through this sub-provincial city governance level are often on a career track to provincial cadre level appointments, which put them on course for high level political power. These sub-provincial leaders are thus positioning themselves now for powerful central roles in the future.

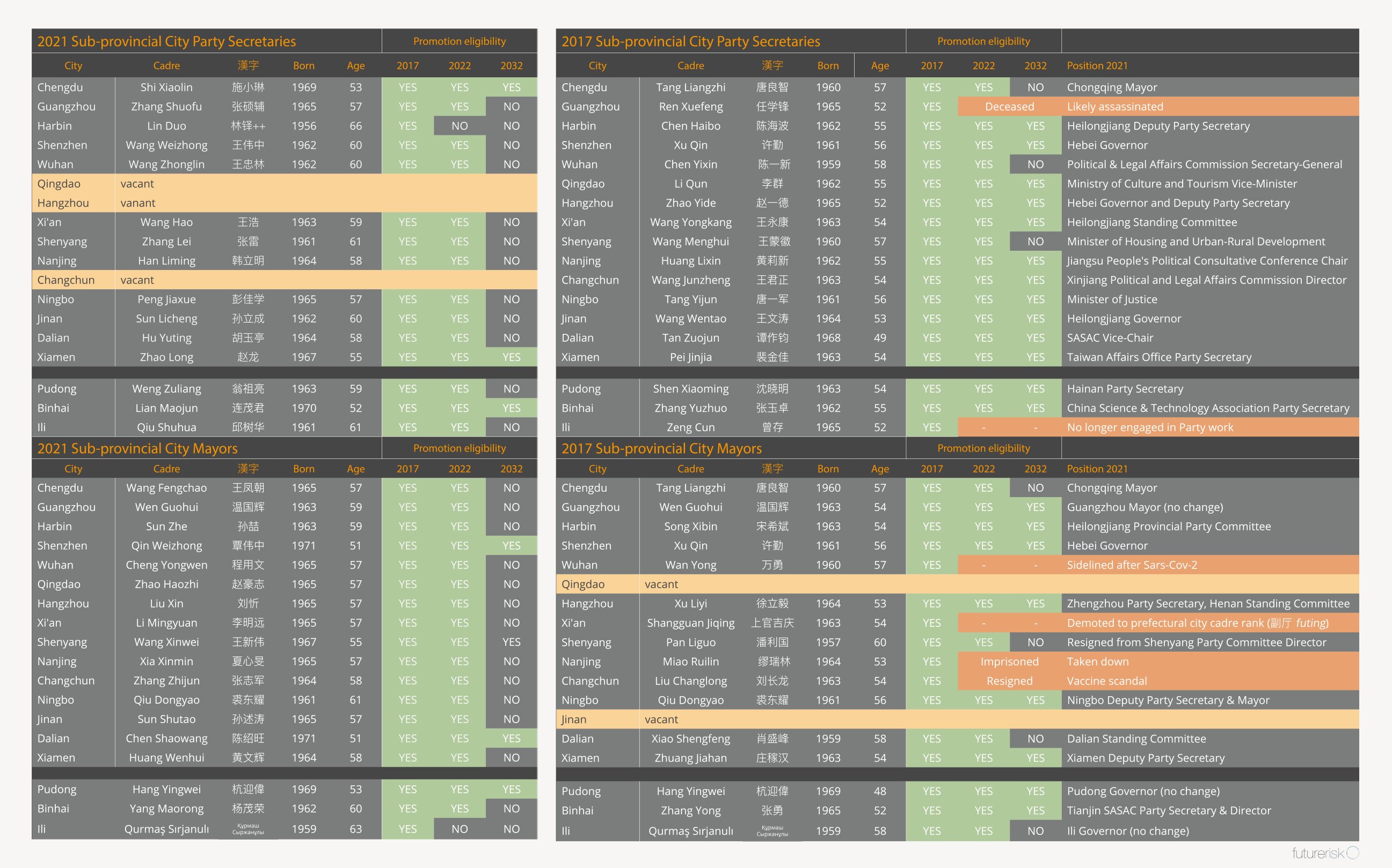

From the 2017 cohort of sub-provincial city Chinese Communist Party (CCP) secretaries, cadres mostly went on to ministerial and provincial level positions. Of those who stayed in the party track and went to central or regional CCP political organs, Chen Yixin, the current secretary general of the Central Politics and Legal Affairs Commission and likely to ascend into the Politburo in 2022, was in 2017 party secretary of Wuhan. Wang Junzheng went from Changchun sub-provincial leadership up to Xinjiang Political and Legal Affairs Commission director. In a less important province, this could be considered a demotion, but after doing CCP work in Xinjiang with Chen Quanguo, Wang will likely be rewarded with a higher climb.

Party secretaries at the sub-provincial level also are promoted to State Council positions at the vice-ministerial and ministerial level. Tang Yijun, former party secretary of Ningbo, is now minister of justice and also a strong contender to go up to the Politburo in 2022. The other full State Council minister from the 2017 sub-provincial city cohort is Wang Menghui, who went from Shenyang party secretary to minister of housing and urban-rural development. Former Qingdao Party Secretary Li Qun is now a vice minister at the Ministry of Culture and Tourism and Tan Zuojun went from Dalian party secretary to a State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) vice chair position.

For those who went to provincial governance, Wang Wentao went from Jinan party secretary to Heilongjiang governor, Zhao Yide from Hangzhou party secretary to Hebei governor, and Wang Yongkang from Xi’an to Heilongjiang Standing Committee. Xu Qin has had an interesting rise from Shenzhen party secretary to Hebei governor and is still young enough to have an impact on central politics. Pei Jinjia went from Xiamen up to the Central Committee Taiwan Affairs Office, where he is now party secretary and vice director. Tang Liangzhi only went up from Chengdu to Chongqing mayor, a predictable though small promotion, but likely solidifying his role in the emerging southwestern power structure centered around Chen Min’er. The least successful of the 2017 cohort was Ren Xuefeng, who after moving up to Chen Min’er’s Chonqging was almost certainly purged at the Fourth Plenum in Beijing – he died from medical issues related to falling from a building.

Zhang Shuofu is the best placed of the 2021 cohort of sub-provincial leaders. Zhang is currently the stop-gap replacement for Ren Xuefeng as Guangzhou party secretary, meaning serious Party loyalty. Guangzhou is the second most populous sub-provincial city after only Chengdu, and with the Greater Bay Area integration project and the National Security Law takeover of Hong Kong, this is a position of both economic and political importance. Zhang is young for such a high position, and could be a bridge of the New Left into the 2030s. Given his recent rapid recent rise, Zhang is likely to be on the fast-track to provincial level leadership and could become a provincial party secretary as early as 2022.

The current cohort also includes Shi Xiaolin, another good prospect for future provincial leadership, especially now that she is ranking within Chen Min’er’s southwest faction. Shi is female and young enough for three promotions, so within the same age cohort as Chen Gang and able to begin factionally positioning for a run at the 2027 power stakes. With United Work Front Department bona fides and vast experience in economically sophisticated Shanghai, Shi is well-placed to take up a smaller province party secretary position sometime in the 2022-2027 period. Han Limin in Nanjing is also a good future prospect for provincial-level leadership. She replaced Zhang Jinghua in June 2021, and was previously mayor of Nanjing and has experience in shipbuilding, a strategic emerging industry. Han also has New Area experience in Jiangbei.

In Xinjiang, the current party secretary of Ili, Qiu Shuhua, is a solid but thoroughly local cadre. She has spent her career in various party positions within Xinjiang, including overseeing Urumqi high-technology zone. She currently is serving as Xinjiang Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) vice-chair, and first political commissar of the Fifth Division of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, which directly governs the strategic prefectural town of Shuanghe, Qiu is unlikely to ever emerge on the national stage, but she will likely be promoted to Xinjiang regional standing committee in the 2022-2027 period. By contrast, Qurmaş Sırjanulı has been governor in Ili since 2017 and is approaching retirement, and has simply been a token ethnicity governance position to ensure stability maintenance.

The Qingdao, Changchun, and Hangzhou party secretary chairs are all vacant as purges have taken out their previous leaders in January, March, and August respectively. The ongoing Hangzhou purge should provide an indication of the intended shape of the CCP once the current rectification pruning is complete. A major difference already clear between the 2017 and 2022 cohort of sub-provincial leaders, though, is the average age: 54.4 and 58.6 respectively. While 13 cadres were eligible for three promotions in 2017, that figure will only be two in 2022, meaning few will be forming into factions capable of lasting into the 2030s.

Categorizing sub-provincial cadres into factions is often speculative until solid interpersonal bonds can be established. Under Xi, the metric for success was personal knowledge of the person in question, but previous metrics had been provincial and regional economic development success. Membership criteria for entry into factional politics thus changes with the dynamic form of the informal factional system itself.

Sub-provincial level cadre leadership, though, is a fraught position; cadres in charge of these jurisdictions are big enough to fall but not strong enough to defend themselves. For most party secretaries at this level in 2022, the only two roads are up to power or down to destruction.