By any measure the 1991 Paris Peace Accords achieved much for Cambodia. Four months after their signing, peacekeepers with the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) arrived and began resuscitating the country, laying the groundwork for elections to be held a year later.

Perhaps $2 billion was injected into a desperately impoverished economy and Cambodians began piecing their lives together after decades of war that included the bloody 1975-79 reign of the Khmer Rouge followed by a 10-year occupation by the Vietnamese army.

The monarchy was restored and a slow process of normalization began that continued long after UNTAC’s mandate ended in September 1993 and perhaps culminated with the U.N.-backed tribunal which has since secured convictions for genocide against Pol Pot’s surviving henchmen.

With the 30th anniversary of the signing, this Saturday, veterans of that era are justifiably lining up to commemorate the rescue of a failed state – but they all have a different perspective and common among many is that the Paris Peace Accords ended the country’s civil war.

As one embassy put it in a blurb for one of the many upcoming events: “The 1991 Paris Peace Agreements were a remarkable example of multilateral diplomacy that ended Cambodia’s decades-long civil war.”

Hardly. The various factions kept their armories, and as unthinkable as it sounds, UNTAC began negotiations that would allow the Khmer Rouge to contest the 1993 election and win a place in Cambodia’s future political landscape.

It’s an issue supporters of the Paris Peace Accords with convenient memories find irritating. But Pol Pot did do Cambodia an unintentional favor by boycotting the historic 1993 poll, which was won by Prince Norodom Ranariddh of Funcinpec, who became first prime minister.

He entered a power sharing deal with Second Prime Minister Hun Sen of the Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) and with the Khmer Rouge lurking in the remote west of the country, the civil war continued.

“The 1991 Paris Peace Accords did not bring peace to Cambodia,” said Michael Hayes, co-founder and former publisher of the Phnom Penh Post, which he established in 1992. “The civil war with the Khmer Rouge lasted another seven years, with about 10,000 more civilian and military casualties.”

“It was an ugly and nasty little war, mostly forgotten by the rest of the world,” he added.

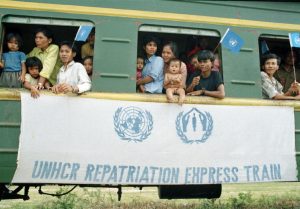

The 1994-95 dry season offensive near Pailin in western Cambodia forced 50,000 people to flee their homes and the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees noted that “the country was back at war even before the last of the peacekeepers left.”

A year later Human Rights Watch noted: “CPP leaders also charged that the ambivalence of Funcinpec soldiers was responsible for the failure of the 1996 dry season offensive against the Khmer Rouge, which resulted in high casualties for the government soldiers…”

As their relationship deteriorated Funcinpec and the CPP armed-up and Ranariddh tried to re-negotiate a deal with the Khmer Rouge to counter Hun Sen, resulting in a showdown in mid-1997 – described by some as a coup, others as another battle in a long running conflict.

Tanks rolled onto the streets of Phnom Penh and Funcinpec was routed, Hun Sen won the election in 1998 amid cries of foul play and then sized-up the Khmer Rouge before unleashing a barrage of attacks on Khmer Rouge holdouts. Amnesties and defections followed.

The remaining senior Khmer Rouge leaders capitulated in December 1998. Pol Pot died under house arrest and, outgunned, “Brother Number Two” Nuon Chea and former head of state Khieu Samphan formally surrendered.

But, as Hayes noted, the Paris Peace Agreements rejigged the entire political equation in Cambodia, which would lead to the Khmer Rouge’s eventual demise.

“Ironically, one of UNTAC’s major failures was, in the end, its major success. The Khmer Rouge pulled out of the U.N. peace process and boycotted the elections in 1993. This left them isolated and alone, devoid of any regional or international support,” Hayes said.

“If the Khmer Rouge had participated in the elections, it is likely they would have won some seats in Parliament, allowing them to move some soldiers into Phnom Penh and that would have given some of their leaders parliamentary immunity from prosecution.”

Instead Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan were found guilty of genocide and Kaing Guek Eav, alias Duch, who ran the S-21 extermination center in Phnom Penh, was convicted of crimes against humanity.

National Defense Minister Son Sen suffered a miserable death. Military chief Ta Mok died behind bars before he could be tried. Foreign Minister Ieng Sary and his wife Ieng Thirith, who served as minister for social affairs, died after they were charged with genocide.

“Imagine what 1997 would have been like if the Khmer Rouge had had 5,000 of their veteran guerrillas at base near Phnom Penh pretending to be integrated government soldiers,” Hayes said.

“Ouch!”

Cambodia is indebted to the 22,000 service personnel from 46 countries who served there. But to claim UNTAC ended the long-running wars is to ignore what happened next and the thousands that perished. They should not be conveniently forgotten.