In recent months, China’s Red Flag River Water Diversion Project Proposal (Red Flag River), an astonishing new inter-basin water diversion proposal, has gained much attention on social media in China and also in the downstream countries, especially in India. Named after the famous Red Flag Canal, the proposal aims to annually divert 60 billion cubic meters of water from the major rivers of the ecologically fragile Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, including three transnational rivers (Mekong, Salween, and Brahmaputra), to arid Xinjiang and other parts of northwest China. Chinese social media posts have portrayed the Red Flag River as akin to a gift from the gods to water-thirsty northwest/northern China, and as another example of China’s extraordinary engineering prowess. Indian media, by contrast, see it as a water security threat.

The project was given a semi-official release in November 2017 by the S4679 Research Group, made up of academicians, professors, and young scholars. Led by Tsinghua University’s professor Wang Hao, they have organized several seminars and forums on the Red Flag River. Their activities have been reported by the Chinese government owned media. As an academician of China’s Academy of Engineering, Professor Wang Hao also serves as the engineer-in-chief of China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research and the chair of the Expert Group on Dialogue for the “Red Flag River Issue.” He has been a core member of the Counselor Advisory Committee of China’s Ministry of Water Resources.

The project has its critics, however. Some Chinese scientists, like Zhang Hongquan, question the project proposal’s enormous cost and raise the likelihood of gigantic domestic water loss. Yang Qinye of the Institute of Geographic Sciences points out that the Red Flag River poses “severe challenges” to many fields – geology, technology, ecology, economy, and society in both the water sending and water receiving regions. Similarly, Yang and co-authors further highlight the Red Flag River’s negative impact on the ecological balance and the water balance within China, which would likely result in changes to the ecosystem, such as habitat loss. However, none of these critical works provide concrete evidence to argue their case, nor do they offer a comprehensive assessment of the Red Flag River.

If constructed, the Red Flag River will be the largest, longest, and most expensive inter-basin water diversion project in the world. Attention has so far been paid to the proposal from an engineering perspective and the benefits of the proposed farmland and oasis, which could be a partial solution to China’s food insecurity concerns. Little attention has been paid to a much bigger picture: how the proposal strengthens China’s water security grid system, which may help solve China’s national water quality, quantity, and unequal distribution issues. This paper discusses how the Red Flag River will expand China’s water grid system and potentially provide “double security” to the North China Plain region.

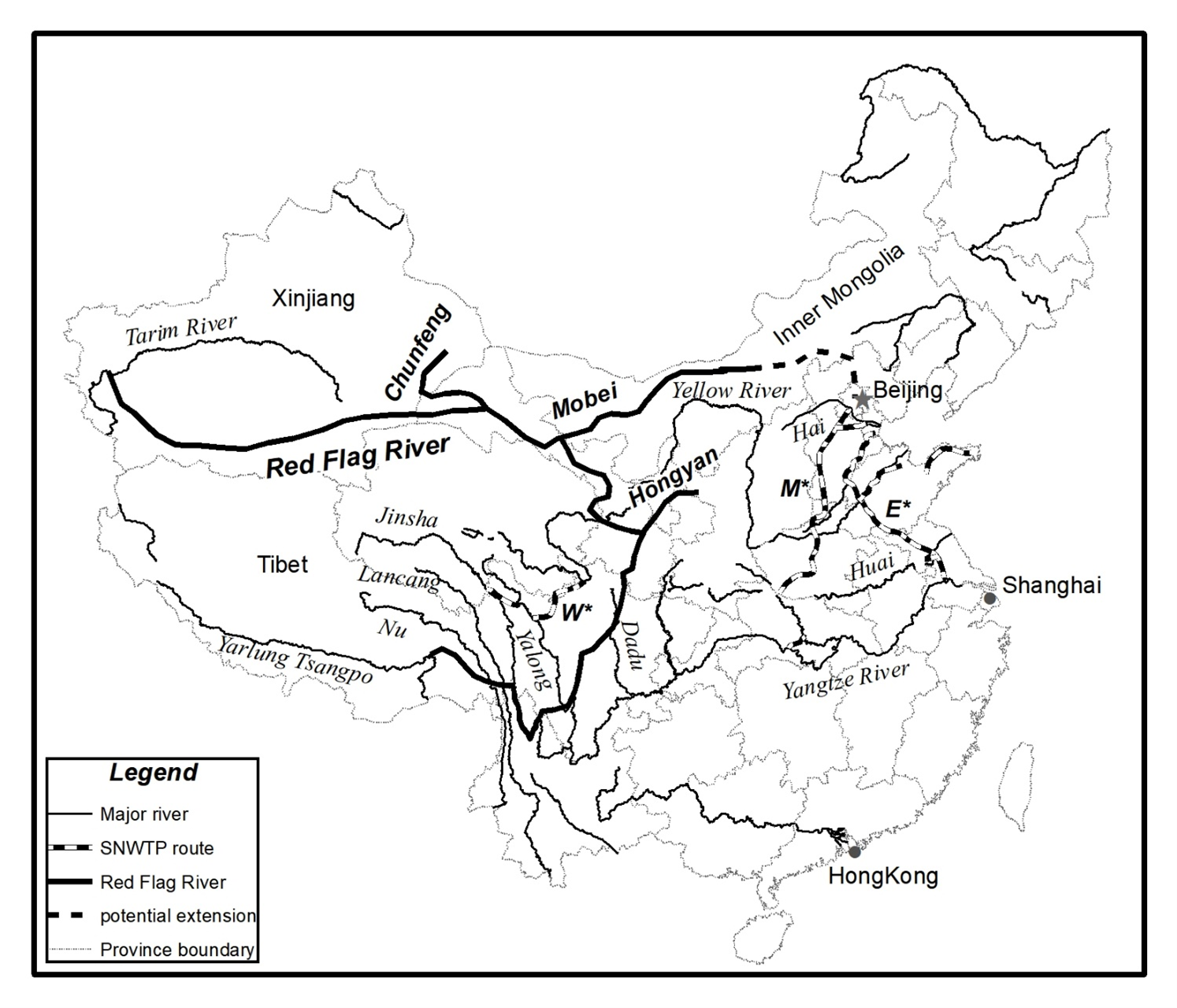

Academics suggest that the Red Flag River is a 6,180-kilometer-long gravity flow water diversion system that seeks “to divert water from Tibet to turn Xinjiang into California.” This could be achieved by using the main channel to send water to southern Xinjiang, all way to Kashi (see Figure 1), while also following the Chunfeng River to divert an enormous quantity of water into the Turpan Basin and northern Xinjiang.

If constructed, the irrigation water from the Red Flag River will be available to Xinjiang and also other arid northwestern provinces, including Gansu and Ningxia. Northwest China is the only water-thirsty region that has not benefited from China’s domestic construction of mega hydro-engineering projects, yet it is also where agricultural productivity is the country’s greatest if water is available. The amount of water to be diverted to northwest China is more than the Yellow River’s annual discharge. This water is expected to create 200 million mu (13.3 million hectares) of arable land in Xinjiang and a 150,000 sq km oasis in northwest China.

Figure 1: Location of proposed Red Flag River and the relevant rivers and the South-North Water Transfer Project routes in China. Authors’ illustration.

In addition to the stated purpose of creating another inter-basin water supply system, we believe the Red Flag River will be able to reinforce the water security of northern China. The completion of the South-North Water Transfer Project (SNWTP) creates a water grid system to secure water supply to Beijing and other major cities in North China Plain – the so-called “sanzhong siheng” (三纵四横). “Sanzhong” refers to the SNWTP’s three routes (the middle and eastern routes have been completed and the western route is in the planning stage); “siheng” refers to the four eastern-flowing rivers (Haihe River, Yellow River, Huaihe River, and Yangtze River). Once the western route of the SNWTP project is constructed, 17 billion cubic meters of water will be diverted from the upper Yangtze to the upper Yellow River in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. This route will likely alleviate the Yellow River’s water stress, including the drying up of the river’s lower reaches.

The Red Flag River will also be potentially able to divert an enormous quantity of water to north China through its two main branches: Hongyan River leading to Yan’an in North Shaanxi province, and the Mobei River flowing into Inner Mongolia and Beijing (see Figure 1). This will reinforce its supply of water resources to the North China Plain via the Mobei branch; Guangzhong Plain and Chengdu Plain (Sichuan Basin) via the Hongyan branch, forming a large water security network.

Why do Beijing and North China need to “doubly secure” the water security system? For many years, China has struggled to find solutions to its water quality, quantity, and unequal distribution issues. The Chinese central government’s solution – the construction of enormous hydro-engineering projects – has not only substantially reshaped the water distribution patterns within China but also reduced water scarcity stress in the water receiving regions, making northern China highly dependent on the SNWTP project. For example, the SNWTP supplies over 70 percent of Beijing’s water supply. Doubling its water supply and safeguarding the water security is a strategic move for this rapidly industrialized and urbanized region – the North China Plain.

Over the past couple of decades, many hydro-engineering projects have been constructed in all regions of China with one exception: the northwest. If built, the Red Flag River will be another mega hydro-project in China, but the first one in northwest China. This paper offers a big picture – it not only creates a new water supply system for northwestern China but also connects to the existing water grid system to strategically “double secure” the water supply to Beijing and northern China. As a new and independent water supply system to northwest China, the Red Flag River proposal is to fill the supply gap.