One of the most beautiful memories I have of Cambodia when I returned to the country in 1992 to work for UNTAC was seeing the ocean and the endless sandy beach of Sihanoukville.

This was my first trip to that town on the Gulf of Thailand, renamed after King Norodom Sihanouk in 1958. Between the civil war and the Khmer Rouge regime in the 1970s, I had never had a chance to go there.

As a child growing up in Phnom Penh in the 1960s, the only long trip I had made was going to visit one of my grandmothers who lived in Battambang City. We had gone by train to meet this very modern grandmother, who wore makeup and served us coconut dessert made blue and pink with food coloring.

Then came the Khmer Rouge’s rule, my fleeing the country to a refugee camp in Thailand and finally immigrating to the United States.

But in 1992, after the Cambodian government and political factions had signed the Paris Peace Agreement in 1991, I was back in my home country, serving as an international polling station officer with UNTAC—the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia. I arrived in Sihanoukville by helicopter, and saw for the first time this beautiful beach on the Gulf of Thailand that I had not even known existed in my country.

Over the years, I would go back many times to Sihanoukville, which many Cambodians still call Kampong Som. But recently, due to many factors, and especially the COVID-19 pandemic, I had not been to Sihanoukville for nearly two years. So to mark the birthday of the late King Norodom Sihanouk – he was born on October 31, 1922 – which is also a national holiday, I recently made the 225-kilometer trip from Phnom Penh.

The Sihanoukville I saw was no longer the city I once knew. Here were streets lined with high-rises, many used as hotels and casinos and others empty or under construction.

And yet, the hill I had climbed on my first visit those many years ago to better see the shoreline and the sea had not been altered.

But first, let me go back to the Sihanoukville I discovered 29 years ago.

Discovering a Lovely Town by the Sea

My first visit to Sihanoukville was wonderful, I would even say magical, starting with the Russian pilot who was so excited that he flew low enough over the gulf for the helicopter’s wheels to splash water.

The town’s population was around 15,000 people in the 1960s. And on that day of September 1992, all we could see was a small town with a huge, long beach. The ocean was deep blue, the sky blue – It was like heaven. Going up that mountain and seeing this beautiful landscape, you felt on top of the world. And nobody was there.

After this first visit, I went to Sihanoukville by car. As an electoral officer assigned to Kampong Speu Province – I worked for UNTAC until the end of the U.N. mission in September 1993 – I got used to travel by road.

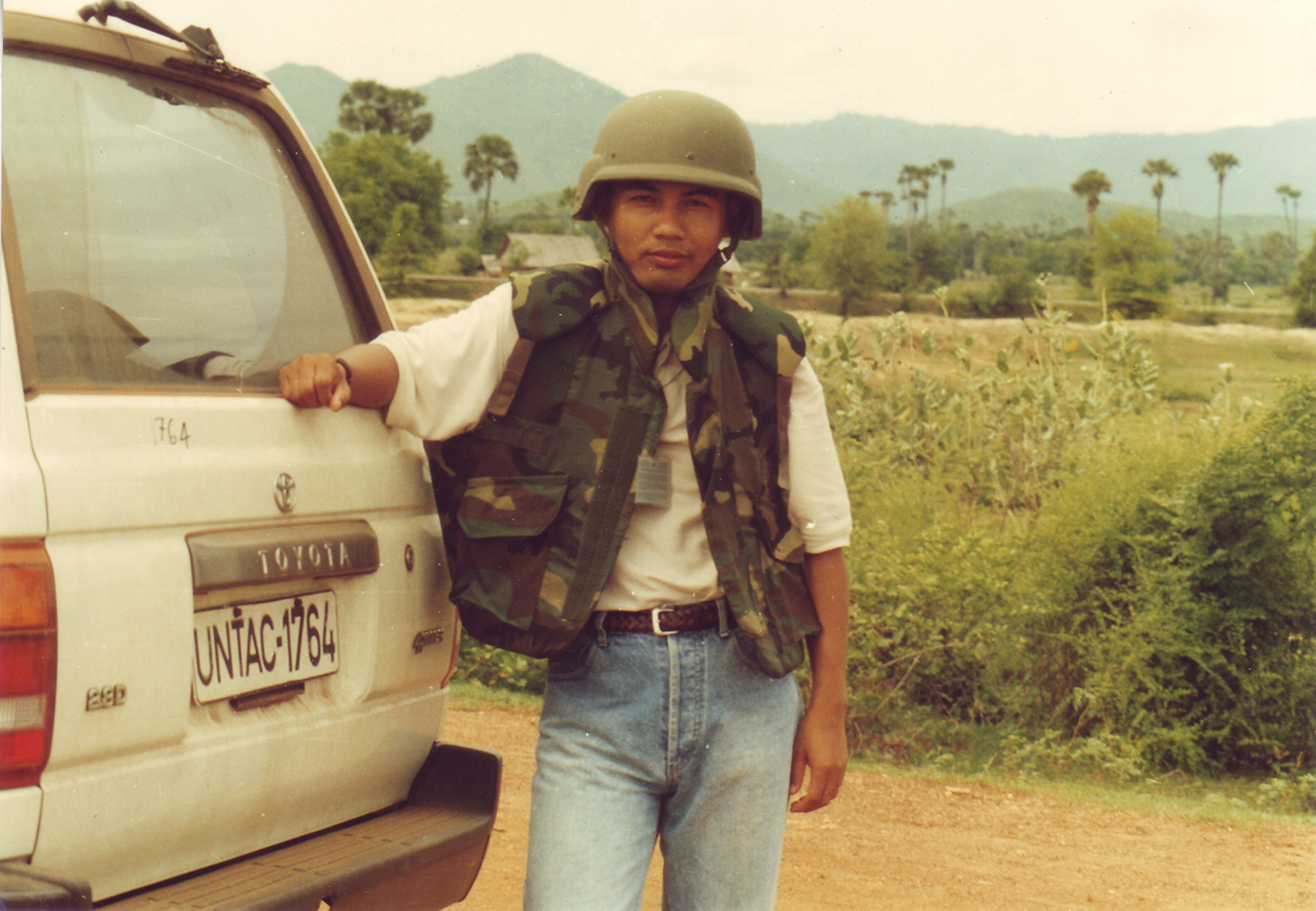

Youk Chhhang in his road-trip gear as UNTAC electoral officer. Traveling by vehicle in the country prior to the 1993 national elections was risky. Photo: Vutha.

One of the problems at the time was the Khmer Rouge trying to disrupt traffic and communications. After signing the Paris Peace Agreement in October 1991, Khmer Rouge leaders had broken it and were determined to disrupt the elections. They attempted to intimidate people, blocking roads and so on, to prevent them from voting. But they would fail spectacularly: In May 1993, nearly 90 percent of those entitled to vote would cast their ballots.

When I travelled for UNTAC, I had to go on specific days so they could provide us with security, clearing the roads in advance. But civilians did not have access to such services when they were off duty.

Still, on a weekend or some holiday after my first visit, I decided to go to Sihanoukville by car. As I expected, we were stopped by the Khmer Rouge. Back then, people were wearing uniforms to threaten UNTAC employees. Sometimes they looked like Khmer Rouge; sometimes they looked like government soldiers. Whoever they were, they would ask for money. Speaking the language, I was able to negotiate and got through.

As a child living in Phnom Penh, I had only heard of Sihanoukville in geography books at primary school. Beside that one exciting train trip to Battambang City, I had only travelled to Takeo Province to see my other grandmother.

Moreover, the road between Phnom Penh and Sihanoukville had been under construction for years in the 1960s. And then, the war had started in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

But it was only 30 years later that I realized how little I had seen of my country. Back then, most Cambodians were not touring their own homeland. Due to many factors – the economic situation, living conditions, transportation – they were not able to explore their country. We did not know much about Angkor or the coastline. Like many other Cambodians, I had only heard of Sihanoukville through music and songs.

A Harsh Reminder of the Khmer Rouge Genocide

In the decades that followed, I would often return to Sihanoukville, at times making this a weekend or holiday outing for my team at the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam).

One visit in 1997 became a reminder that the fear the Khmer Rouge inspired was still very present in the country.

For the holiday weekend of October 31, marking the birthday of King Sihanouk, I had decided to take my family to Sihanoukville. When I arrived in Sihanoukville, there were no people around. At the hotel, the manager told us that a government official was expected. Soldiers and police officers had basically shut down the town for his arrival.

The manager also told us that I could not get the rooms I had reserved, even though I had had paid in advance. This was the best hotel at the time and the manager could not say no to government officials. The hotel had maybe 10 rooms and they had reserved them all. So, the manager offered to let us stay with the hotel staff members in their small rooms.

I left my sister and mother at the hotel and went out on an errand. When I called my sister later on, she was so scared she could hardly speak. She was trembling on the phone. I asked her what was wrong.

“The Khmer Rouge are here,” she said. “The Khmer Rouge are at the hotel.”

It was Ieng Sary, the former Khmer Rouge leader who had defected and joined the Cambodian government in 1996. And my sister was worried for me because I was investigating the Khmer Rouge at DC-Cam. As for me, I was wondering why they were bothering my sister. Did the Khmer Rouge still want to threaten my sister and mother, who were their victims?

When I came back to the hotel, there were bodyguards all over but since many knew who I was, they let me in. I went to reassure my mother and sister. We felt like we were in a Khmer Rouge prison again.

Later in the day, I sent Ieng Sary a note, asking to interview him regarding some documents of the Khmer Rouge regime. At 10 p.m., his assistant Long Narin told me to come to his room, which I did. We talked for a while. He told me the documents seemed right and invited me to come to Pailin, an area in the western part of Cambodia that was under Sary’s control.

That night, I couldn’t sleep. I wanted to make sure nobody knocked on the door. It was a familiar feeling from the Khmer Rouge time – be prepared to resist and fight. I told myself I would not let anything happen to me again. I would not let the Khmer Rouge touch us.

In the meantime, I wrote down the details of the encounter and sent this to The Cambodia Daily newspaper, whose national editor I knew personally. I just wanted to let him what had happened, as a precaution.

I got up at 5:00 a.m. and went downstairs, but the lobby was empty. I had been left a note, which I later passed on to the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), also referred to as Khmer Rouge Tribunal.

In the note, Sary said he would make time for me later. Being so young, he questioned how I dared to research the Khmer Rouge regime of Democratic Kampuchea – but if I wanted to do so, I should come to Pailin. It was about two or three lines. I read that message 10 times, trying to decide if it was a letter of invitation or a threat.

With them gone, it was as if we had just come out of the Khmer Rouge again. People in the hotel were smiling, relaxing now that the Khmer Rouge were gone.

On my way back to Phnom Penh, I got many calls from reporters: They wanted to get details of my encounter with Ieng Sary. The Cambodia Daily had actually published the letter I had sent as a precaution.

Then I got a call from a Cambodian in United States who said, “Coward, why didn’t you kill Ieng Sary? You should have shot him.” The man said he had lost his mother and several family members during the Khmer Rouge regime. I told him that, first of all, I did not carry a gun, and secondly, I advocated a process of justice: I did not want to do to Ieng Sary what he did to us.

Ieng Sary would later be tried at the Khmer Rouge Tribunal for crimes against humanity; he died in detention in 2013 before the verdict was rendered.

Ieng Sary during the Trial Chamber hearing in Case 002. Photo by the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, December 5, 2011.

The Beach Belonged to Cambodians

In the 2000s and the early 2010s, I often went to Sihanoukville.

Like other NGOs and businesses, I would take my whole staff there for holidays, for annual meetings. I put them on a big local boat to go to the islands off the coast so we could explore them. We swam in the middle of the ocean. And then we would watch the sunset disappear into the gulf.

We always stayed there at least two nights, the whole staff. It’s so beautiful; I wanted my staff to really know the sight. And by then, there were many inexpensive places to stay.

As many Cambodians started going to Sihanoukville, you could see fortune tellers by the ocean, kids selling papayas or pineapples, and adults selling crafts.

Cambodians learned about swimwear and taking long walks on the beach, all those things that two decades of war and conflicts in the 1970s and 1980s had prevented them from doing. The beach belonged to them. You could see the change. Sellers started to carry beach clothes and merchandize that would appeal to a Cambodian clientele and not only to visitors.

Then the authorities began to talk of keeping the beach clean, having the food outlets some distance from the water. A bus service started.

I have always encouraged my staff to get to know their own country so they can have the courage to protect it – even though it’s a challenge at times – because it is so beautiful.

As soon as the COVID-19 travel restrictions were lifted and people could travel again, I started sending staff members to various locations. I tell them: You must see your own country because it is YOUR country, you know.

By the late 2000s and 2010s, Cambodians had become familiar with all the sports and activities to be enjoyed off and on water at the beach. Photo from the DC-Cam Archives, 2014.

A few weeks ago, in October 2021, I decided to go to Sihanoukville with some of my staff to see the changes I had heard had taken place in and around the city. Due mainly to the pandemic, I had not been there since 2019.

When I arrived, I felt so empty. I could not breathe. What I knew of Sihanoukville no longer existed. I couldn’t feel the breeze.

I was disoriented, trying to figure out what that intersection was, where this street led. Every move was a question for me to answer. Then I got fed up with myself: Why am I asking so many questions? This is Sihanoukville.

Most of the buildings we saw were unfinished and empty. People told me that, due to COVID-19, the investors – mostly Chinese – had left but were now coming back one by one.

The buildings that were finished were mainly hotels and casinos. No banks, multinational or business buildings – at least that I could see.

Sihanoukville felt empty in spite of all these buildings – empty in the way that one loses one’s sense of belonging. It looks like somewhere else, not Cambodia. The street does not belong to Cambodians any longer.

Still, the new builders seemed to be using the old masterplan of the city, which goes back to the 1960s. They have just widened the streets to turn many into boulevards.

At a hotel restaurant, the Chinese seemed to stay among themselves. One member of my staff who speaks Chinese was seated in the Chinese section, while we were later put in another. The Chinese use their own products – there was no Kampot pepper or other Cambodian supplies. Even toothpicks and napkins were imported from China. Maybe this is premature, and they will eventually use Cambodian products, but this is an issue that must be raised.

As for the public beach, there still is one where people can swim, but it is farther away. We were actually told that that public beach had been sold and that the company owning it may eventually turn it private.

But these were rumors. Let’s assume that the Cambodian government has made sure there will always be a public beach in Sihanoukville, and that Cambodians will have the chance to enjoy it.

At the hotel where we stayed, many staff members had come from elsewhere in the country to work, having lost their jobs due to the pandemic. Their dream today has become survival. Based on what we heard, there was little or no training at hotels as guests who came to gamble only require basic service.

One food server kept looking at the gulf, mesmerized. When I asked her about it, she told me she was from Pursat Province and had never seen the ocean.

Sihanoukville today, a landscape of hotel and casino high-rises. Photo by Youk Chhang, October 30, 2021.

What the Future Will Hold for Sihanoukville

While I worked as an election officer for UNTAC, I met Ted Ngoy, who had launched the Free Development Republican Party. He was a Cambodian who had lived through the Khmer Rouge regime, arrived as a refugee in the United States in 1985, made a fortune with a donut chain, lost it gambling, and yet had sponsored more than 100 Cambodian refugee families to the United States in the late 1980s. A documentary film on him entitled “The Donut King: the rags to riches story of a poor immigrant that changed the world” was released in the United States in 2020 and is available online.

During the electoral campaign in 1993, Ted would say that, if he was elected, he would turn Sihanoukville into another Hong Kong, one of the biggest centers for economic growth in Southeast Asia.

Because of Ted Ngoy and his dream, because of Ieng Sary and the fears he had instantly brought back, and because of the beauty that had taken my breath away when I first saw its beach in 1992, Sihanoukville is a mix of contradictory memories and feelings for me.

And as I saw recently, it now is yet another world, one that has yet to be defined.

Still, I was able to find the road up that mountain where I had gone on my first visit as a UNTAC electoral officer. It’s still untouched, that mountain. It now stands in the middle of the city, but it has not been altered.

Note: Information on Sihanoukville in the 1950s and 1960s can be found in the Queen Mother Library that was set up by DC-Cam in 2020 with the support of the U.S. Embassy and USAID in Cambodia. Located a short distance from Independence Monument off Street 19, it contains a large number of files of and about King Norodom Sihanouk over several decades.