The great scramble for COVID-19 vaccines, with unequal access for the less wealthy nations, has propelled a great many Asians to turn toward their indigenous health systems for protection and relief from the virus.

The dismally slow rate of vaccine roll-outs across the region and the developing world galvanized alternative health care practitioners and scientists to test the efficacy of local herbs with anti-viral potential. It was a move warmly welcomed by large sections of the general public, especially the many millions who still have more trust in traditional, rather than Western, medicine.

By the end of 2020 pharmacies in Thailand were overwhelmed by customers stocking up on well-known anti-viral Fa Talai Jone (Andrographis paniculata), also known as Green Chireta, commonly used for colds and influenza.

U.K.’s Boots chain of pharmacies happily displayed in its Thai branches bottles of another herb, Krachai Chao (Boesenbergia rotunda or finger-root, a member of the ginger family). Commonly used in Thai cuisine, it was suddenly elevated from an ingredient in Thai and Burmese curries to the status of a “Wonder Herb” that could treat COVID-19.

From a Western viewpoint this public clamor for herbal medicine might appear to be fanciful if not delusionary, but the rush for herbal medicine should not be passed off as a temporary fad, given the deep roots of traditional health systems in Southeast Asia.

Dr. Kwanchai Wisitthanon, who graduated from medical faculty of Chulalungkorn University in Bangkok, works for the Ministry of Health as deputy director of a special Department of Thai Traditional Medicine (DTTM). He explained that many herbs have been tested in medical laboratories. In an interview with The Diplomat, Kwanchai reported that “Fa Talai Jone had demonstrated it can kill the COVID-19 virus in lab spike protein tests. It can also prevent the COVID virus from entering cells, prevent reproduction of infected cells and reduce degree of infection.” It is now clear, Kwanchai adds, that Fa Talai Jone “can stop mild symptoms of COVID-19 and reduce severe symptoms.”

The strong current of public belief in Thailand in the potential efficacy of herbal treatments for COVID-19 was vindicated when the Fa Talai Jone herb was officially approved by the Thai Cabinet for the treatment of asymptomatic and mild case of COVID-19 in December 2020.

A Boots pharmacy branch in Thailand offers “Goodbye 19,” finger-root tablets supposed to help treat COVID-19. Photo by Tom Fawthrop.

In Asia, both allopathic medicine (the Western system) and the holistic tradition have been more or less integrated and to a considerable degree harmonized. Both approaches now co-exist inside health ministries. In China, India, Indonesia, South Korea, Thailand, and Vietnam, traditional medicine is highly respected and integrated within their public health services.

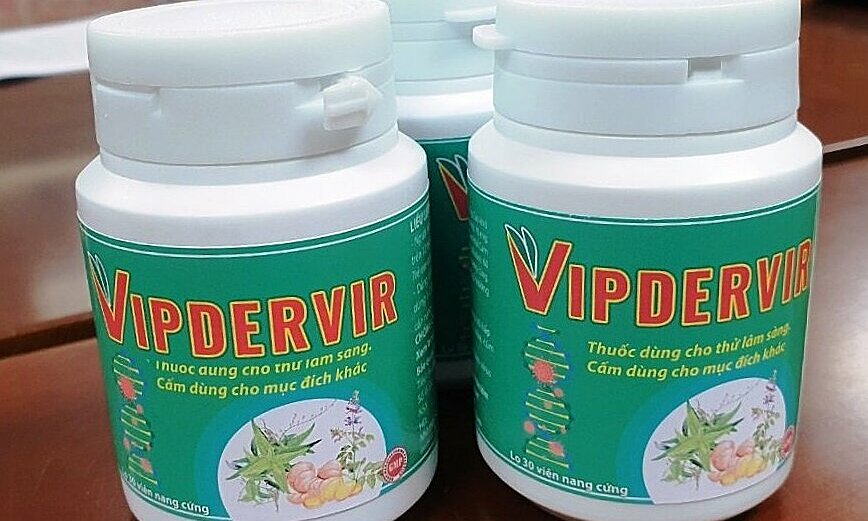

In Vietnam associate professor Dr. Le Quang Huan’s research team at the Institute of Biotechnology used bioinformatics technology to screen various herbs in the creation of a nature-based anti-COVID-19 candidate called Vipdervir. A cocktail of different herbs, it has been approved for validation in a clinical trial.

Vietnamese researchers report that traditional medicine can be used in complement with modern medicine for synergistic effects on SARS-related diseases. The Science Direct journal reported Vietnam’s Ministry of Health facilitated the use of herbal medicine for the prevention and complementary treatment of COVID-19.

Vipdervir, a Vietnamese herb-based treatment for COVID-19.

Much of the public frenzy over finger-root, another anti-viral herb, was triggered by the assessment of Dr. Suradej Hongeng, assistant dean of Research Affairs at Mahidol University‘s Faculty of Medicine in Bangkok, announcing that finger-root can completely kill the virus without causing any harmful side effects. He told the Bangkok Post, “We believe finger-root is the answer, and we are now in the process of making it in a drug form to fight COVID-19 in the very near future.”

Several Thai media reports soon triggered a business boom resulting in a plethora of new brands of finger-root supplements grabbing prominent space in pharmacies. It also provided a huge boost for Thai farmers. In Nakhon Sawan, farm households were earning 5,000-7,000 baht a day selling finger-root.

It is no surprise that some pushback emerged on the rush to commercialize the “wonder herb.” Professor Banchong Mahaisavariysa, the rector of Mahidol University issued a statement that: “This university has nothing to do with claims by product advertisers that extracts from finger-root, or Chinese ginger (boesenbergia rotunda), can kill the virus, or stop the spread of COVID-19 in humans.”

Mahidol University had first announced the discovery that finger-root was a potential weapon against COVID-19, but was anxious to debunk any suggestion that private companies were in any way linked to their research. In addition, scientists want to make clear that results from test-tube experiments cannot prove the herb can block COVID-19 virus in humans. That claim will remain unproven until the results are known from clinical trials.

Raw finger-root on sale in Thai markets. Photo by Tom Fawthrop.

The regulatory status of Fa Talai Jone is more advanced than finger-root as it has been included in Thailand’s list of essential medicines since 1999, and now re-purposed as for treatment of mild symptoms of COVID-19.

The health ministry’s DTTM unit is also researching the potential benefits of cannabis oil for long-term sufferers of COVID-19, estimated to number about 200,000 people in Thailand.

With media attention so deeply immersed in the latest vaccine developments of Big Pharma, “anti-vax” protests, and lockdown fatigue, the growing importance of traditional medicine in Asia has been largely ignored by Western media.

The crisis of vaccine shortages in the first six months of this year has now been sorted out, with substantial supplies of Sinovac, AstraZeneca, and Pfizer enabling Thailand to administer 98 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines. On this basis of each person receiving two vaccinations, that means 70.4 percent of the country’s population are now fully vaccinated.

With pharmacists reporting a drop in sales compared to the boom period, in part a response to the big improvement in vaccine supply, some observers might assume that traditional medicine had lost its relevance for dealing with the pandemic.

But that is not the case. Doctors like Kwanchai advocate for vaccinations, but also believe that traditional medicine still has an important complementary role to play alongside Western medicine. That’s especially important with the rise in the Omicron variant, which causes more breakthrough cases in vaccinated patients.

In treating COVID-19 patients with mild symptoms, doctors claim Fa Talai Jone has decided advantages over repurposed drugs used by Thai hospitals – including remdesivir and others – given that the herbs can be easily self-administered at home and have far fewer side effects.

Takeshi Kasai, WHO regional director for the Western Pacific has also expressed support with the statement that “Traditional and complementary medicine services that are evidence-based, safe and of assured quality are valuable in contributing to a holistic, patient-centered approach to achieve health and well-being.”

If the clinical trial results for finger-root and Fa Talai Jone are successful, in 2022 we can expect to see even greater therapeutic use of these herbs not only in Thailand but also in many neighboring countries. Given that the Omicron variant could lead to many more cases in Asia with mild symptoms, the region may well need to count even more on nature-based solutions.