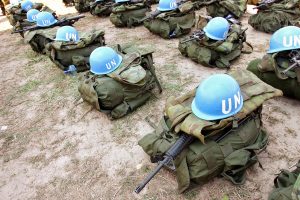

Images of Kazakh troops wearing United Nations-branded blue peacekeeping helmets, while handling stun grenades during protests in Almaty, crossed a blue line. Anti-government protests that began on January 2 have led to over 160 Kazakhs being killed, thousands injured, and thousands more detained. Despite the violence, the U.N. is not deployed in Kazakhstan. The U.N. has issued a statement asking Kazakh leaders to show “restraint,” and U.N. human right experts condemned the government for labeling the protestors as “terrorists.” Notwithstanding such “a war of words,” these “Little Blue Helmets” – fake U.N. peacekeeping troops – are using a false flag to repress Kazakh citizens. The international community must respond to the unsanctioned use of an internationally protected symbol.

Abuse of U.N. regalia did not start with Kazakh forces. Belarusian peacekeepers have been pictured wearing subdued UN. peacekeeping patches, too. The misuse of U.N. insignia violates international norms and laws, akin to misidentifying forces with Red Cross logos.

The costume worn for war – or not worn – has major geopolitical implications. For instance, Russia was able to maintain strategic ambiguity when they used “Little Green Men” – Russian troops without any insignia – to invade, occupy, and annex Crimea. The use of “Little Blue Helmets” in Kazakhstan contributes to this growing trend of more and more countries violating the rules, norms, and laws of warfare – and “peacekeeping.”

Just as Russian “peacekeeping forces” illegally occupy about one-fifth of Georgia to this day, Russia sent “peacekeeping troops” to Kazakhstan. These troops fell under the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). Approximately 3,000 Russian soldiers deployed, alongside some 500 troops from Belarus, 100 Armenians, 200 Tajiks, and 150 Kyrgyz, to protect critical infrastructure and to conduct a so-called “counter-terrorist operation” described on Twitter by Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev. These CSTO peacekeeping forces were not U.N. peacekeepers. With Tokayev appearing to have regained even tighter control of his country, CSTO forces are already returning home.

Sometimes no choice is itself a choice. There is real danger in letting such a transgression pass with nothing more than a verbal rebuke, as given by U.N. spokesperson Stéphane Dujarric against leadership in Almaty for the unsanctioned use of U.N. symbols. No strong international response to this violation of international law, not to mention the brutal crackdown in Almaty, carries major consequences for the international system.

First, the blue U.N. symbol provides propaganda value to the Kazakh regime through positive looking optics. Blue helmets give the illusion of authority and legitimacy to the Kazakh crackdown, but at the same time, it also contributes to the degradation of the U.N.’s image and the growing perception of it as a weak international institution. If Tokayev manages to stay in power, as he appears set to do, his success will incentivize other regimes to mirror such illegal practices. Other unauthorized uses of internationally-legitimated symbols for potentially-illegitimate military operations will follow.

History tells us small violations tend to gather and grow. Give a little, and you may lose a lot. Fake blue helmets will erode U.N. credibility, and contribute to the erosion of international norms of behavior, much like what happened to the League of Nations in the 1930s. The League of Nations – a precursor to the U.N. – failed to reprimand Japanese and Italian invasions of China and Ethiopia, respectively.

Then there is the issue of credibility. Then-U.S. President Barack Obama’s now-famous “red line” comment on Syrian chemical weapons in 2012, and subsequent inaction when said “line” was crossed in 2013, was viewed as a major debacle. Kazakhstan has crossed another brightly colored line with its use of fake U.N. peacekeeping forces. The international community – besides the U.N. – must meaningfully respond against Kazakhstan for using “Little Blue Helmets,” especially for admitted offensive counterterrorism purposes.

Unfortunately, there is not much the U.N. can do. In 2010, the U.N. wagged its finger at India, asking New Delhi not to use fake U.N. peacekeeping troops against separatists in Kashmir. That seemed to work. In the case of Kazakhstan, Russia is a permanent member of the U.N. Security Council and would likely neutralize any strong U.N. response. Russian veto power protects Kazakhstan, a country President Vladimir Putin wants nestled in his sphere of control, lest he end up in a similar situation of losing Ukraine and Georgia to the West.

Already, the Kazakh Permanent Representative to the U.N. has responded on Twitter to these “Little Blue Helmet” allegations, posting that “In fact, all necessary measures were taken to prevent the use of any equipment bearing the ‘UN’ inscription in the counter-terrorism operations in Almaty.” Such a statement flies in the face of multiple images of Kazakh forces wearing blue helmets with “U.N.” inscriptions, which could have easily been covered or marked out. Regardless, U.N. officials should suspend Kazakhstan from U.N. peacekeeping operations for the next five years. This would signal to others that unsanctioned use of the U.N.-symbol carries reputational damage, not to mention preventing your troops from participating in (and profiting from) U.N.-authorized peacekeeping missions.

Western capitals, particularly Brussels, must punish Kazakhstan (and Belarus) for misusing U.N. logos. Moscow’s protective warnings mean there is no single silver-bullet Western response, but Kazakh penalties should be delicate and well-crafted. Western intelligence agencies (even public organizations like Bellingcat), could easily identify the leaders that ordered units – presumably the KAZBAT 38th Air Assault Brigade of the Airmobile forces – to improperly don blue peacekeeping helmets and flag them for reprimand and sanction. While these KAZBAT troops likely possessed and used these helmets because Kazakhstan routinely contributes peacekeeping forces, that does not excuse their illegal use in Almaty. Kazakh commanders and leaders would have known better based on the fact that Almaty hosted a 2020 Staff Officer Course at its own peacekeeping school.

Second, countries might suspend existing security partnership programs with Kazakhstan. The U.S., for example, has had an annual training partnership with the Arizona National Guard for nearly three decades, with Kazakhstan having received $782 million in U.S. military aid since 2000. U.S. leaders should have known better. Based on past behavior, evidence suggests that U.S. military-donated Humvees were likely used by that same KAZBAT peacekeeping unit during 2011 December anti-government demonstrations in Zhanaozen, which led to the deaths of at least 17 protesters.

While the U.N. cannot defend itself, there is still leverage here. Western leaders have several tools at their disposal to stop Kazakhstan’s military from improperly wearing U.N. regalia – and to deter future violations. Strong diplomatic and economic sanctions against Kazakhstan would protect the image of the U.N. today, while protecting the sanctity of the U.N. and its rationale for promoting peace, human rights, and mediating conflict.

Without a robust response to offenders crossing a “blue line” as Kazakhstan did, the next “Little Blue Helmets” crisis might involve Russia or China using fake U.N. peacekeeping troops to salami slice another piece of territory in Ukraine or Taiwan. Not only would such a predicament be militarily difficult for the international community to respond to, it would be a bad look for the West and could even be a death knell for the U.N.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the United States Air Force Academy, Air Force, Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.