Alarm bells are ringing in Washington, D.C. over an issue considered to be so vital to U.S. moral and strategic imperatives that congressional foes have joined forces in an effort to resolve it. In a political climate where it seems every issue is charged with rancor and division in Washington, the lack of resolution in mapping out future ties between the U.S. and three Pacific island nations has brought unlikely congressional partners together.

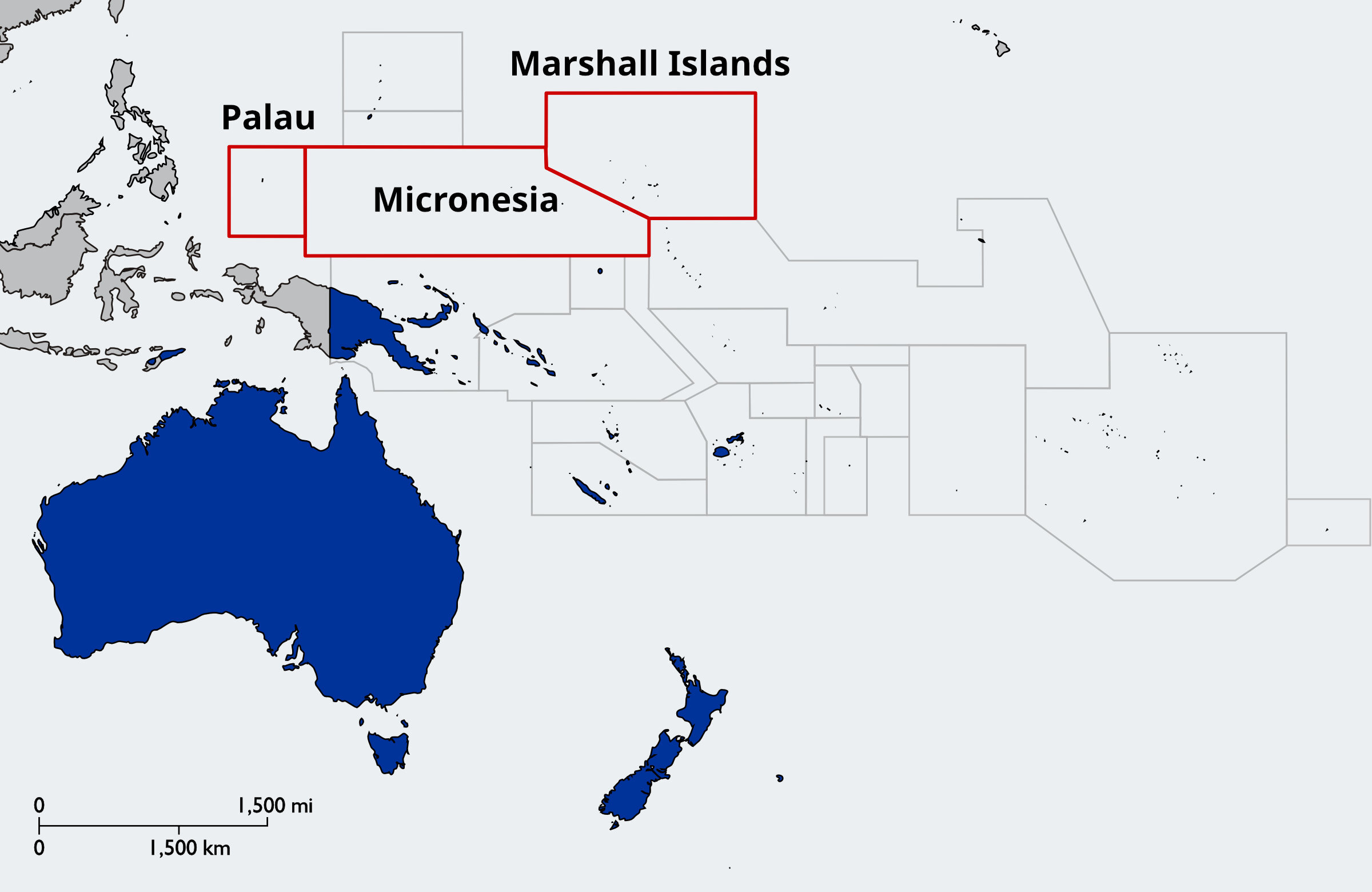

Why? The drawing up of the future relationships between the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI), the Federated States of Micronesia (Micronesia) and the Republic of Palau (Palau) and the U.S. touches on every priority area for the Biden administration, and Democrats more broadly, as well as deep concerns for Republicans. There are glaring social justice and racial equality issues. Climate change is an uniquely urgent, existential crisis for these low-lying island countries. Marshallese residents in the U.S. have tragically experienced deaths and hospitalizations from COVID-19 at disproportionately high levels, prompting a special CDC inquiry. The pandemic has highlighted mass economic inequities, lack of access to healthcare, and problems with the unique immigration status that citizens from these three countries have in the U.S. And finally, but by no means least, there are the strategic dimensions of the U.S. relationships. These three nations’ borders cover an immense area of the Pacific Ocean that in the age of acute competition with China is of the highest strategic importance. In addition, Palau and the RMI both host vital military bases. In recent days the Pentagon has announced these nations as possible sites for additional military installations, an eventuality that hinges entirely on the future roadmap of their U.S. relationships.

The reason why there is such alarm in some halls of American power right now is that the Compacts of Free Association (COFA) between the U.S. and these three nations should now be in the advanced stages of renegotiation before they expire in 2023 and 2024 in the case of Palau. Yet there is an unsettling lack of action on this front. In the case of the most complex negotiation, that with the RMI, there have been no formal meetings since December 2020.

Ahead of a bipartisan congressional hearing in October 2021 that focused the issue of the U.S. nuclear legacy in the RMI, a letter was written to the Biden administration requesting urgent action in restarting negotiations on the three compact agreements. At the time of writing, there still has been no developments on this front despite repeated overtures from the three COFA nations. This inaction has created a sharp schism within the U.S. government. On one side is the unlikely coalition of congressional leaders who passionately support a prompt and just resolution to the negotiations. On the other side is the executive branch and several departments – mainly State, Energy and Interior – that manage critical aspects of the U.S. relationship with the COFA nations relevant to their own area, creating a piecemeal approach. Despite assurances that resolving these compact agreements is “a high priority,” as representatives from the Department of Energy and Office of Insular Affairs with the Department of Interior assured the October 2021 congressional hearing, this is clearly far from the case. The Department of State even declined to send a representative to this hearing.

With fears currently running sky high about a Russian invasion of Ukraine and China’s ambition to retake Taiwan, it is still nonetheless vital to not forget the critical relationships the U.S. enjoys with its three loyal COFA allies. Of all the complex international issues currently facing the U.S. this one could be characterized as low-hanging fruit, yet it is not receiving its due attention.

Understanding the unique relationship these nations have with the U.S. requires knowing the underlying history. The islands that now comprise the RMI, Micronesia, and Palau came under U.S. jurisdiction in 1946 as United Nations Trust Territories. Prior to World War II, they had been under Japanese military control from 1914 and then mandated to Japan by the League of Nations from 1921. In World War II, the U.S. occupied numerous islands as they advanced toward Japan in the Pacific theater’s final phases.

Less than one year after defeating Japan in September 1945, the U.S. selected Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands to begin its atomic testing program. The first test of Operations Crossroads in July 1946 marked the start of a nuclear history that has bound the U.S. to the Marshall Islands ever since and has profound importance in the compact currently in need of renegotiation. From July 1946 until 1958 the U.S. detonated 67 thermonuclear tests, equivalent to “the detonation of 1.7 Hiroshima bombs every day for 12 years.”

The radioactive legacy of this testing program is extraordinary and still profoundly impacts the RMI’s population, which numbered around 53,000 in 2011 but declined to 39,300 by 2021 due to out migration. The first nuclear refugees from islands contaminated by the testing program (Bikini, Rongelap, Utrik, and Enewetak) began migrating to the United States in the 1970s, though many more people from all three nations began arriving in the mid-1980s to found the array of communities spread across the U.S. today. It is the presence of significant COFA communities in their congressional districts that have brought together representatives like Katie Porter (a Democrat representing California’s 45th District), Steve Womack (a Republican from Arkansas’ 3rd District), Ed Case (a Democrat from Hawaii’s 1st District) and Amata Radewagen (a Republican representing American Samoa), who on virtually any other issue would span the political spectrum.

Migration from the mid-1980s from home islands into the U.S. was the direct result of the three nations’ shift in status from their essentially colonial attachment to the U.S. to independent nations “freely associated” with the United States. Under the compact agreements, COFA citizens were permitted access to the U.S. to live and work and they were granted access to federal welfare programs. However, a bureaucratic error in 1996 stripped COFA citizens of their rights to basic programs like Medicaid and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Restoring access to these programs has been a 25-year campaign that only recently started to be resolved.

COFA citizens have come to the U.S. for educational, health, and work opportunities with a very high proportion having served in the U.S. military. The level of military service is a fact proudly emphasized by all three nations as it exemplifies their commitment to their alliances with the U.S. and their fulfillment of compact obligations. In exchange, the U.S. provides economic assistance and has “unlimited and exclusive access to the land and waterways” of the three nations. The U.S. also operates vital bases with its compact partners, like the Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defense Test Site on Kwajalein Atoll in the RMI.

The acute effects of climate change are driving increased migration out of the home islands and into the United States. In addition to land inundation by seawater, islands in the RMI and Micronesia are also in the grip of a crippling drought. These conditions combined with the economic impacts of COVID-19 on home islands will likely lead to more out migration once borders, closed since March 2020, reopen. Border closures have protected home islands from COVID-19. The RMI (with the exception of four cases in October 2020) and Micronesia are two of the few countries remaining without any COVID-19 cases. This was the case with Palau as well until January 2022, when the Omicron variant evaded strict quarantine measures, as it has elsewhere in the Pacific Islands in recent weeks.

In the context of escalating tensions between the U.S. and China, the COFA states have a unique position beyond their paramount strategic importance. Palau and the RMI are two of the last nations that diplomatically recognize the Republic of China government on Taiwan. Micronesia, by contrast, has had diplomatic relations with China since 1989 and has been expanding that relationship in conspicuous ways in recent years, to the point where Micronesia has been recently described as “the next U.S.-China battleground”. Yet Micronesia is widely relegated to the status of COFA partner of least importance in Washington, largely because it does not host military installations or have the nuclear legacy that shapes the U.S. relationship with the RMI. This is a situation that also clearly needs to change.

U.S nuclear legacies in the RMI are at the forefront of the problems endemic with COFA negotiations more broadly. The convergence of rapidly rising sea levels due to climate change has brought the issue of the nuclear waste dump on Runit Island in the Enewetak Atoll to the recent attention of Congress. In the final years of governing the Marshall Islands as a Trust Territory, the U.S. constructed a nuclear waste dump where contaminated materials from atomic weapons testing in the RMI, but also from Nevada, were relocated and sealed under a concrete dome completed in 1977.

The Runit Dome, initially intended as a temporary structure, is deteriorating and seawater is “communicating” with the radioactive contents inside, as the Department of Energy representative testified during the dedicated congressional hearing in October 2021. During this hearing it became apparent the Department of Energy continues to withhold vital scientific findings about Runit Dome from the RMI government. Also, Department of Energy officials contradicted each other on whether required monitoring of the dome has been conducted and are unclear about the department’s legal obligations relative to the dome. The process of declassifying relevant historic documents relating to the atomic testing program and its ongoing aftermath is underway as of December 2021 (the RMI is also seeking the translation of vital documents into Marshallese for the first time). Meanwhile, the Department of Energy has undertaken to conduct tests, which were delayed due to the pandemic, to ascertain the extent of leakage from the Runit Dome in 2022. This is a timeline running parallel with the compact negotiation, raising well-founded concerns that critical data will not be available to inform those negotiations. As it currently stands, Runit Dome issues are not on the compact negotiation agenda that has been set by the U.S., to the ongoing frustration of the RMI government.

From every angle, the COFA negotiations are urgently in need of the highest level of attention and remediation. The clock is at one minute to midnight on all the justice, climate, and strategic aspects of U.S. relations with the COFA nations. It is high time to heed the alarms. It is high time to heed the alarms, and Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s recently issued invitation to Pacific leaders to participate in meetings on February 12, when he is in Fiji, may be a sign that the U.S. is starting to do so.