Amid the tragedy of war in Ukraine, the roles of major powers are coming into question. With regards to China, there is a view that Russia President Vladimir Putin is not afraid of sanctions because China will provide an economic lifeline to Russia. On the other hand, China’s abstention from a draft United Nations Security Council (UNSC) resolution that would have deplored Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which Russia vetoed, was interpreted as a diplomatic win by both Russia and the West.

How do we understand the role that China has played in the Russia-Ukraine conflict so far, and how much can China help Russia?

Chinese Views of the Conflict

To understand China’s actions and potential role, we have to begin by looking at Chinese views on the conflict in Ukraine. While China’s official position on the conflict has been consistent with its foreign policy regarding international conflicts, major power competition, and the current world order, online opinions among the Chinese public are divided.

It is possible that China was taken by surprise over Russia’s move into Ukraine, judging by Chinese spokespersons’ comments before the invasion, Chinese experts’ predictions, and the lack of preparations of the Chinese embassy in Ukraine, but we can only speculate on that.

China’s official stance on the conflict at press conferences and in diplomatic talks with both Western and Russian leaders has been that sovereignty and territorial integrity should be respected. What’s special this time is that China emphasizes that the situation in Ukraine is not what China wishes to see, that the sovereignty of states includes that of Ukraine, and that China is determined to defend the legitimate rights of small and medium powers. It is an indirect but clear expression of opposition to Russia’s military action, which is extraordinary in Sino-Russian bilateral relations. Reports of the official Xinhua News Agency from Ukraine have also focused on the insecure situation and humanitarian crisis on the ground.

At the same time, China has strongly criticized the United States for escalating the conflict. It has largely blamed the U.S. for causing the war for the purpose of maintaining its declining hegemony. China regards the conflict as a proxy war in which the U.S. got others to go to war on its behalf and Ukraine became a frontline of major power rivalry. When official statements say that the Cold War mentality should be dropped to resolve the Ukraine conflict, China is referring to the U.S., as Beijing frequently mentions Washington’s military alliances in the Asia-Pacific as an example of American Cold War tactic. Therefore, China expresses understanding of Russia’s security concerns, and it urges Europe to create a new security mechanism – one without the U.S.

Online Chinese public opinion is polarized into two main groups. One group of opinion is sympathetic to the Ukrainian people and condemns Putin for waging war. This group discusses whether China should join the West in imposing sanctions on Russia. The other group of opinion sees the United States as the real culprit and empathizes with Putin’s stated need of defending the motherland. It sees the U.S. using the excuse of defending democracy to expand its hegemony as the root cause of the conflict, just as it did in the Kosovo war in 1999, during which three Chinese journalists were killed when a NATO bomb hit the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, which the U.S. denied was intentional. It also criticizes the West for having double standards in tolerating the U.S. bombing of Yugoslavia while condemning Russia’s invasion in Ukraine.

A nationalist sentiment, though, is widely shared that it is because of China’s economic and military power today that the Chinese people can enjoy peace. That could be one reason why the government has so far tolerated widely diversified opinions on this sensitive and emotional issue, but it also reflects the government’s complex views on the conflict.

China’s Actions During the Conflict

China’s actions follow its script for being a responsible great power in world affairs. Since the war in Darfur in 2003, and in particular since the beginning of the Libyan crisis in 2011, China has played an increased role of conflict mediation. China’s style of mediation is to urge conflicting parties to hold talks and halt military actions. Sometimes China offers to host the meetings either separately or jointly with the conflicting parties. Just as it did during the Iran-Saudi Arabia tensions in 2016, as well as the recent internal conflicts in Afghanistan, South Sudan, Syria, and Myanmar, China calls for all parties involved in the Ukraine conflict to use restraint and resolve conflicts through dialogue.

At the same time, China tries to avoid being involved in conflicts. It participates in U.N. peacekeeping forces but is against unilateral military intervention outside the aegis of the U.N. This time, China has said that it would not offer to provide Russia with weapons.

Before military conflict erupted in Ukraine, China advocated negotiations based on the Minsk Agreement II in 2015 and the Normandy format that involves France, Germany, Russia, and Ukraine. After the tensions escalated to military conflict, China called for direct dialogue between Russia and Ukraine. China cited Putin’s agreement to hold high-level talks with Ukraine in his phone call with Chinese President Xi Jinping on February 25 as an example of China’s constructive role. The level of activity of Xi and Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s calls with their Russian, Ukraine, and European counterparts is unprecedented and can perhaps only be matched with the handling of the COVID-19 crisis in recent history. This shows not only China’s wish to play a great power role in conflict mediation but also Beijing’s worry about conflict escalation.

China’s message has been clear: dialogue and civilian lives are a priority; China is a friend of both Ukraine and Russia and will not pick a side; and all parties must try to deescalate the conflict. China also advocates a balanced, effective, and sustainable European security mechanism. This can be interpreted as being a mechanism that is not joined or dominated by the U.S., can support European strategic independence, and can address the security concerns of multiple parties, including Russia, over the long term.

As mentioned, China abstained from a draft UNSC resolution on February 25 that would have deplored Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which Russia vetoed. China’s abstention was interpreted as a diplomatic win by both Russia and the West. China has expressed opposition to lenient usage of Chapter 7 of the U.N. Charter about sanctions and authorization of military force, and it is reported that a reference to Chapter 7 in a draft of the UNSC resolution was removed. China was reportedly persuaded by the West to abstain from instead of vetoing the draft resolution, but abstention for China means acquiescing, and China would not acquiesce to something that endorses military action. China was surprised after its abstention on a successful U.N. resolution to impose a no-fly zone on Libya in 2011 was followed by Western airstrikes over Libya, and therefore China is expected to veto U.N. resolutions that authorize military action (except peacekeeping).

China earlier supported U.N. sanctions on the nuclear programs of Iran and North Korea and on the former Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, but in general China is against sanctions. China may also be carefully watching the impacts of Western financial and technological sanctions on Russia so that it can better evaluate the risks and be prepared for such a scenario for itself.

How Much Can China Help Russia?

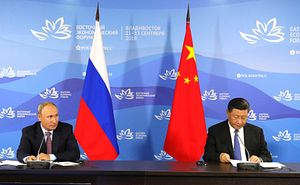

During Putin’s visit to Beijing for the Winter Olympics, the two countries signed a series of cooperation agreements on February 4 covering trade and investment, anti-monopoly, low-carbon development, sports, satellites, and digitalization, including China’s import of wheat, gas, and oil from Russia. The two countries proclaimed a “no limits” friendship with “no forbidden areas of cooperation” and released a lengthy joint statement. This signals that China and Russia have come closer together from an earlier friendship of convenience that lacked deep strategic trust and have solidified their relations because of their shared perception of the U.S.-led Western containment targeting both countries.

The West’s handling of the Ukraine crisis pushes Moscow and Beijing further into a long-term strategic partnership that is committed to reforming the world order against U.S. domination.

However, in the short term, the tangible support that China can provide to Russia is limited and will have little impact on Russia’s resources for continuing war. It is notable that the West has largely exempted oil, gas, and grain from sanctions, which are Russia’s major exports. So the talk of China providing a lifeline to Russia in the short term is not that relevant. China has not taken measures to expand economic cooperation with Russia since Moscow sent troops to the Ukrainian border but has started implementing the agreements signed on February 4. Increasing grain and energy imports from Russia helps with China’s food and energy supply, and the West’s sanctions on Russia increase China’s negotiating power vis-à-vis Russia. However, China’s imports will not be able to fill in the economic void caused by sanctions.

In an agreement signed on February 4, China lifted restrictions on wheat imports from Russian regions that were earlier banned for reasons of disease control. While Russia has become the world’s biggest wheat exporter, with over 38 million tonnes of exports in 2020-2021, China has kept a quota of total annual wheat import at 9.3 million tonnes in order to maintain national food security.

On February 4, China and Russia also signed two agreements on gas and oil supply worth $117.5 billion. The China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) and Russia’s Gazprom agreed to provide 10 billion cubic meters (bcm) of Russia’s gas supply to China per year through the Far Eastern route. (Under an earlier long-term gas agreement, Russia began supply gas to China in December 2019 through the Eastern route or Power of Siberia 1 pipeline, which would reach 38 bcm per year by 2025.) By comparison, Nordstream 2 was expected to send 55 bcm of natural gas per year to Europe. The agreement between Rosneft and CNPC on the supply of 100 million tonnes of oil to China through Kazakhstan over 10 years is effectively an extension of an existing arrangement.

In the longer term, Russia can diversify more of its energy exports to China from the West, and as China sees natural gas as a cleaner alternative to coal and oil, its demand for gas is predicted to grow rapidly, doubling by 2035, according to one estimate. But it takes time to construct pipelines or expand the capacity of existing lines. Gazprom announced in January that together with China it would jointly construct a Power of Siberia 2 gas pipeline, which will start sending gas in two to three years, up to 50 bcm per year. In comparison, Russia exports between 150 bcm and 190 bcm of gas to Europe each year. If Europe managed to find other gas suppliers than Russia, Russia would need to find potential buyers other than China.

More severe short-term impacts on Russia may come from the financial sanctions. In January, China and Russia agreed to establish their own financial information transmission systems to avoid sanctions that block them from the U.S. dollar-denominated SWIFT system. The two countries have their own systems, CIPS and SPFS, denominated in the Chinese renminbi and Russian ruble, respectively, and the RMB and ruble are convertible, so technically it should be easy to establish a joint system that serves China-Russia transactions. The question is how attractive their alternative to SWIFT will be for their trading partners.

Looking at the bigger picture, an escalation or prolonged Ukraine conflict would bring chaos to international capital markets, supply chains, and global economy as a whole. That is not what China wishes to see at a time when a post-COVID-19 recovery is badly needed and when China is at a crucial juncture of economic restructuring.

There are numerous geopolitical risks as well. The EU is China’s biggest trading partner, and China will try to maintain normal relations with the EU as well as its member states. China still has hopes for Europe to become one solid pole in the formation of a multipolar world with more strategic independence from the United States. China also needs to ensure domestic stability ahead of the important Party Congress in autumn this year, which is expected to extend Xi’s term in office. The conflict with Russia may distract Western powers’ attention and resources from the South China Sea and Taiwan, but heightened tensions in global politics are not conducive to China’s development plans or its ambition of national rejuvenation.

At a deeper level, the events and the roles of various parties in the Russia-Ukraine conflict could entrench China’s strategic judgment of the current world order as one characterized by major power competition and the Western determination, led by the U.S., to uphold its dominance. The trade war with the United States made China frame the current time as a period of strategic opportunity that forces China to strengthen itself in an adverse international environment. The Russia-Ukraine conflict could strengthen the framework for extraordinary and nationalistic Chinese policies.