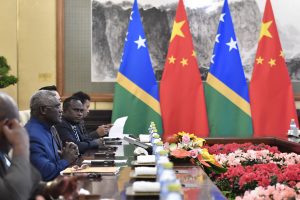

All the attention on China’s recent security pact with the Solomon Islands has shone a light on the concept of Australia’s regional sphere of influence. Why does Australia feel alarmed that an independent neighboring nation has brokered an agreement with China?

Australia’s prime minister, fighting what he thought would be an advantageous “khaki” election campaign (although it is not unfolding as he hoped), talked this week about a “red line in the Pacific” being drawn that Australia, and the U.S., will enforce in as yet unspecified ways. Australia’s defense minister escalated the rhetoric by telling Australia’s voters that they should “prepare for war.” The rhetoric from the Australian government is hot – red hot – and a dangerous election tactic that has been met with fiery responses from China and the Solomon Islands’ prime minister, Manasseh Sogavare. It paints a menacing scenario for Australia’s voters that taps into deep wells of anxiety about the country’s vulnerabilities that stretch back into the 19th century, when Australia was a collection of British colonies with national unity (realized in 1901) then a distant ambition.

Taking the lead from the United States’ 1823 declaration by President James Monroe that deemed any European nation asserting imperial power in the Americas as an act of hostility toward the United States, Australian politicians began deploying the term Australia’s “Monroe Doctrine” in the 1870s. For Australian politicians, the expression articulated the fundamental security imperative of keeping Australia and the islands adjacent to it out of the “grasp of competing powers.” “Competing powers” in the late 19th century referred specifically to France and Germany. The Dutch had long held present-day Indonesia and were not considered a comparable threat to Australia’s security. France began a bold foray into the western Pacific in 1853 when it annexed New Caledonia and then commenced creating a settler society there much like the British had done in Australia from 1788. From the 1870s, anxieties intensified when a newly unified Germany rapidly began entering into the imperial game.

The Pacific Islands – at first in New Guinea and Samoa – were bringing Germany too close to Australia for the comfort of many politicians. Fears of great power footholds in Australia’s near region were repeatedly used to drive British imperial claims to assuage anxious colonials. These fears propelled Britain to annex the Solomon Islands in 1893, but left France and Germany to take other islands in the archipelagoes arcing the continent’s northeast, with present-day Vanuatu jointly run by both Britain and France. These developments led one Australian newspaper article in 1897 to presciently predict that in the future “we will have to spend millions … because of the nearness of bases of possible hostile operations.”

Here we are in 2022 – 125 years later – and the sentiments of Australia’s Monroe Doctrine would not sound that out of place in the current election campaign (though “millions” would need to be upped to “billions”). The old anxieties about Australia’s vulnerabilities remain relatively unchanged, but the geopolitical order onto which these anxieties are now mapped is fundamentally different.

The islands arcing Australia are now sovereign nations with the exception of New Caledonia, which recently rejected independence from France. Adding more regional complexity, the Autonomous Region of Bougainville is on course to become independent from Papua New Guinea in the near future. Furthermore, China is now the rising great power in question. Its size, regional location, approach to the islands, and historical ties to the region put China on a very different footing in the current strategic game playing out in the Pacific islands.

Australia’s demographic landscape is also a critical factor. Paradoxically, with all the talk about “Australia’s Pacific family,” very few people from Australia’s nearest neighbors are represented in Australia’s migrant community (0.88 percent in 2016). This is the result of consistent policies of racial and, after 1975 when the “White Australia” immigration policy was abandoned, economic barriers that have kept Pacific populations at bay. (The Pacific communities resident in Australia have come via the “New Zealand pathway,” mainly from Samoa and Tonga). In all the “us and them” rhetoric about Australia and China it needs to be remembered that 5 percent of Australia’s population is of Chinese descent, and the number of China-born Australians rose almost 59 percent between the 2011 and 2016 census. How these demographics will impact the upcoming election will be interesting in seats with large Chinese populations.

Australia’s Monroe Doctrine is an anachronism that the China-Solomon Islands security deal is bringing back to life but in a very different geopolitical and domestic landscape. It is the elephant in the room everyone is carefully trying to step around with mixed results. Prime Minister Scott Morrison defended his government’s response to the deal, claiming they did not want to repeat the “long history” of telling Pacific nations what to do. Morrison added: “I’m not going to act like former administrations that treated the Pacific like some extension of Australia.” That might be the case, but it has resulted in some confounding choices made by the government.

Despite Morrison’s statement, the colonial past lingers because there has not been sufficient framing of Australia’s policies toward the Pacific around what the Pacific wants and needs. Climate change action is the foremost deficit in Australia’s current Pacific approach. Confusion on the election campaign-trail about the government’s and the Australian Labor Party’s (ALP) emissions and coal policies (because the ALP wants to win seats in coal country) will have a marked impact on Australia’s Pacific relations going forward. This week, the Australian Labor Party announced their Pacific policy, which they claimed was a sharp departure from the status quo and designed to repair relations and stem China’s influence. Climate action is part of it, though how this works with subsequent statements about coal is unclear.

The other planks of the ALP’s Pacific policy – which Morrison described as “farcical” – revolve around bolstering defense training and cooperation, reinstating the Australian Broadcasting Corporation in the region, and overhauling the Pacific Labor Scheme, which currently is framed around Australian labor shortages rather than the capacity building needs of Pacific nations. The program has also been roundly criticized for exploiting Pacific Islanders in revelations that could not have come at a worse time for the government.

The ALP’s latest announcement of its plan to issue 3,000 “green cards” giving permanent residency to Pacific families is a positive step forward in building much needed people-to-people relationships and opening Australia up to its Pacific neighbors to live and work on beneficial terms. This will start building new bridges with its region as well as bolstering Pacific economies that desperately need infusions of cash and opportunity. What this program must then be matched with are educational opportunities and pathways to citizenship. These are the kinds of policies that are going to negate the colonial legacies of Australia’s Monroe Doctrine mindset and secure Australia and the surrounding island nations through mutual benefit, shared democratic values, and the domestic integration of Australia with its region.