The controversial new security deal between the Solomon Islands and China has become a prism through which all other components of Pacific geopolitics, indeed the geopolitics of the greater Indo-Pacific, will now be refracted.

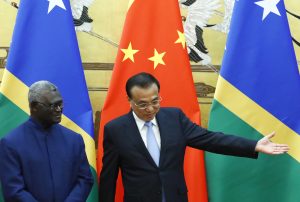

A draft of the deal, leaked on social media on March 24, set off an immediate firestorm. A chorus of pleas came from domestic and international quarters alike, requesting the Solomon Islands’ government, headed by Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare, step back from the deal. Instead, Sogavare fiercely rejected all criticism and expressions of “grave concerns” and on March 31, China and the Solomon Islands began formalizing the agreement. Now Sogavare’s troubled nation and the Indo-Pacific region must grapple with the extensive consequences of this game-changing development.

The new security agreement has far-reaching domestic and geopolitical implications. The two contexts are now dangerously interwoven, with the greater geopolitical contest between China on the one side and Taiwan, the United States, Australia, and other allies on the other mapped onto long-standing and increasingly precarious domestic tensions. These tensions have regularly erupted into conflict throughout the 44 years since the Solomon Islands gained its independence from Britain in 1978.

A decade of tensions between settlers from other islands (mainly from Malaita) on Guadalcanal erupted into armed conflict in 1998. In 2000, the Townsville Peace Agreement, which Malaitan leaders want revived as a salve to the current tensions, was signed between combatants. But it did not deliver peace because it was not fully enacted, according to those who see it as the path forward to resolving domestic tensions. With unrest continuing, Australia-led peacekeepers were in the Solomon Islands from 2003 until 2017, as part of the Regional Assistance Mission of the Solomon Islands (RAMSI).

The China-Solomon Islands security agreement comes only four months after peacekeepers from Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, and Papua New Guinea again came to the assistance of the Solomon Islands in late November 2021 following the urgent request of Sogavare. Days before, peaceful protests made up mostly of men from the island of Malaita were in the capital, Honiara, calling out what they saw as Sogavare’s punitive treatment of Malaita for maintaining a pro-Taiwan stance after Sogavare dramatically switched the national allegiance to China in September 2019. After the Malaitan protestors were roughly confronted by Solomon Islands police, the peaceful protests devolved into a deadly spree of looting and arson that centered on Honiara’s Chinatown. Warnings had been issued by Maliatan leaders that peacekeepers were propping up Sogavare’s unpopular and corrupt government and, in doing so, were carrying out China’s work.

Only four months later, these warnings have been proven correct. Not only does Sogavare firmly grip the reins of power, thanks to the recent peacekeeping interventions, but his government’s power is now guaranteed by China. As a result, a recalibration of Pacific geopolitics is now needed.

Exactly what the Solomon Islands and China have agreed to is not clear, as the final version of the pact has been kept secret, it appears, from all but a select few government ministers. Sogavare has stressed that the secrecy surrounding the security agreement was not nefarious but rather an assertion of his nation’s “sovereignty.” Yet, as former Solomon Islands Prime Minister and Member of Parliament Rick Houenipwela has pointed out, if it were not for the leaked document “the security treaty would be kept a secret from citizens of this country,” which is a dubious means of asserting a democracy’s sovereignty.

Sogavare’s recent comments on the security deal, and the speed with which it has been formalized, suggest that the final inked version is very close to the leaked draft. That six-article document was laden with vaguely defined terms and powers that would permit Beijing enormous inroads into the Solomon Islands. It would allow large-scale and varied Chinese military and intelligence operations. Most concerning, it permits China to become heavily involved in maintaining civic order through the deployment of “police, armed police, military personnel and other law enforcement and armed forces.”

Solomon Islands’ sovereignty would supposedly be protected by thinly detailed triggers and weak powers controlling Chinese intervention, such as the power of activation for the agreement and “consent” for Chinese naval visits being retained by the Solomon Islands’ government. Yet the inclusion of the phrase that supposedly gives both nations power to act “according to its own needs” has elevated concerns about the latitude this agreement offers China to expand its military power into the southwest Pacific.

Also deeply concerning is that the agreement provides “legal and judicial immunity” for all Chinese personnel. Solomon Islands academic Transform Aqorau cites this as one of the most troubling aspects of the deal, writing that “it is ironic that a prime minister who invariably extols the virtues of national sovereignty should agree to cede a fundamental sovereign function – the protection of lives and property – to a foreign force.”

Solomon Islands’ history virtually guarantees the kind of civic disorder that could trigger Chinese boots on Solomon Islands ground. This scenario is made even more likely given the nation’s financial distress, made worse by the 2021 riots (though Sogavare has denied this) and the devastating arrival of COVID-19 in the form of multiple variants at once to the Solomon Islands from January 2022. On top of those issues, more internal dissent has erupted due to the China deal. Sogavare’s government has issued a number of notably strident warnings to opponents in the past days. On April 4, his government denied reports that the security deal threatens to split the Royal Solomon Islands Police Force (RSIPF). These are very worrying developments given the fragile state of Solomon Islands’ democratic institutions (especially as an election is due in 2023) that will no doubt inflame the smoldering coals of conflict.

Given all these pressures, it is not difficult to foresee a potential scenario where a conflict between the proxies of China and the U.S. and its allies, could occur – with devastating effect – in the Solomon Islands. There is no question that security in the Solomon Islands is greatly undermined by this agreement, despite Sogavare’s assertions to the contrary.

But what about the implications for security in the region and the wider Indo-Pacific? The upcoming 80th anniversary of the September 1942 Battle of Guadalcanal, which devastated U.S. and Japanese military forces and cost many Solomon Islanders’ lives, is a deeply sobering reminder of the enduring strategic importance of the Solomon Islands. This is especially the case for Australia, which lies just over 3,200 kilometers away. Solomon Islands stretches over critical Australian sea-lane and communication routes.

Solomon Islands is also of the highest strategic importance to its near neighbors of Papua New Guinea and the new nation emerging from its Bougainville Autonomous Region, which lies just north of the Solomon Islands border, as well as Fiji and New Zealand. New Zealand signed a “partnership agreement” with Fiji on March 29, following revelations of the existence of the Solomon Islands-China security deal, and this follows a major upgrade of defense cooperation between Fiji and Australia in mid-March 2022.

Opinion has been sharply divided about whether China will use the security deal to build a military base in the Solomon Islands. Sogavare, and those unperturbed by the deal, insist China will not build a military base to project its power into the southwest Pacific. Solomon Islands scholar Tarcisius Kabutaulaka argues that “China is unlikely to build a naval base in Solomon Islands” because “foreign military outposts are not how Beijing operates.” Kabutaulaka further argues that unlike the United States, which operates 750 bases in 80 countries, China operates “only one overseas base in Djibouti in the Horn of Africa.”

That may be the case, for now, but China’s past overtures to Vanuatu in 2018, and Papua New Guinea in 2020, and activities at the Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka, Gwadar Port in Pakistan, and the Ream Naval Base in Cambodia, and now the Solomon Islands, when connected together tell another story. It is unlikely that such a provocative move as building a Chinese military base would happen in the short-term, but China continues to play a long and complex strategic game. Sogavare has continued to try to quell concerns by saying “Australia remains our partner of choice, and we will not do anything to undermine Australia’s national security,” though such words are cold comfort given his recent actions.

While a military base might be a longer-term scenario, the revelation of the Solomon Islands-China deal has had already had an impact on U.S. and allied approaches to the Pacific (like the recent agreements between Australia and New Zealand with Fiji). A case in point was the U.S. Senate Hearings on the Compact of Free Association Negotiations held March 29. That hearing gathered evidence from the Departments of State, Defense, and Interior about the mired state of U.S. government negotiations with the Republic of the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia and the Republic of Palau.

There had been great frustration that these negotiations have not progressed significantly since December 2020 (even though the current compacts expire starting in 2023), until March 22 when Ambassador Joseph Jun was appointed Special Presidential Envoy for Compact Negotiations. Despite this key development, which should now allow these critical negotiations to progress, the Solomon Islands-China deal loomed over proceedings. Senators sought answers about why there had been such seeming dysfunction and lack of action on the COFA renewals when China was surging ahead and making critical inroads into the region, as the Solomon Islands deal makes clear.

One would now hope that the pace and extent of U.S. Pacific Islands engagement will grow exponentially as a result. There should also be sweeping reforms in how the United States and its allies approach to Pacific Islands in order to prevent a repeat of this agreement being made elsewhere in the region. The Solomon Islands story is one deeply shaped by the mechanics of Chinese elite capture and lost diplomatic opportunities. For instance, the United States only announced in February 2022 that it planned to reopen its Solomon Islands Embassy, which has been shuttered since 1993. Slow, inconsistent and business-as-usual approaches have failed.

This attention to the Pacific is long overdue, but it will come at a big price. In the words of Solomon Islands opposition leader Matthew Wale, Sogavare perceives “China as a genie that will act on his beck and call.” Sogavare has released this genie from the bottle by signing onto the China security agreement; now the costs for his country, and the region, may be far higher than he bargained for.