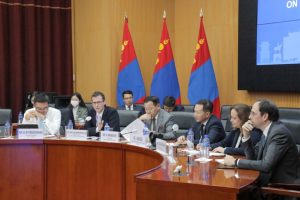

The Mongolian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Institute for Strategic Studies organized the seventh Ulaanbaatar Dialogue on Northeast Asian Security international conference from June 23 to 24. Mongolia’s hosting of such a timely event manifests the country’s successful foreign policy mechanisms.

Since its establishment in 2014, the Ulaanbaatar Dialogue has served as a non-traditional mediation platform where representatives from Northeast Asian countries can discuss security issues impacting the region. Despite the two-year COVID-related hiatus, Mongolia was able to gather more international participants for the resumed dialogue than in previous years.

Since the late 1960s, Mongolia’s foreign policy began to pursue a more active role in global affairs. Mongolia’s relentless efforts to gain membership in the United Nations were a prelude to many of its later foreign policy mechanisms.

The Ulaanbaatar Dialogue on Northeast Asian Security platform was initially inspired by the Helsinki Accords of 1975 – the culmination of two years of negotiations under the Conference for Security and Cooperation in Europe (eventually institutionalized into the today’s Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, or OSCE). The objective of the conference, hosted by Finland, was to reduce tensions between the Soviet Union and the Western bloc. Borrowing from the idea that a country can be a mediation platform became part of Mongolia’s foreign policy strategy to engage its Northeast Asian partners and establish a trust through the practice of diplomacy and mutual respect.

In 2011, the parliament of Mongolia renewed and modernized the country’s Foreign Policy Concept, which enabled Ulaanbaatar to expand its participation in Northeast Asia and East Asian affairs at large. In 2013, the then-president of Mongolia, Elbegdorj Tsakhia, became the first head of state to visit Pyongyang after Kim Jong Un assumed power. Elbegdorj announced the establishment of the Ulaanbaatar Dialogue at the seventh Ministerial Conference of the Community of Democracies in Ulaanbaatar.

During the first Ulaanbaatar Dialogue in 2014, Grayvoronskiy V. Viktorovich from the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences noted Mongolia’s initiation to be more active in regional diplomacy. He also noted, “There are many other regional and permanent international institutions, conferences, meetings, and dialogues… the Ulaanbaatar Dialogue needs to find its niche among the other international institutions and meetings.”

Given Mongolia’s unique geopolitical position and its normal diplomatic relations with all the countries in Northeast Asia, Mongolia itself provides the “niche.” For example, when it comes to the perennial issue of the denuclearization of North Korea, Mongolia’s status as a non-nuclear weapons state gives it a unique discursive role. Other countries in the region either are nuclear powers (China and Russia) or have little to no diplomatic contact with North Korea (South Korea and Japan).

Moreover, Mongolia has previously made some efforts to mediate between Japan and North Korea on Pyongyang’s previous abductions of Japanese nationals. Former Japanese Foreign Minister Kono Taro sought to utilize Mongolia’s diplomatic relations with North Korea as a channel to negotiate with Pyongyang. To the countries in the region and the international community, Mongolia’s diplomatic relationship with North Korea presents an opportunity for promoting peace and dialogue.

At the same time, North Korea is not the only security issue in Northeast Asia. Some of the regional relationships, such as Japan-China, Japan-South Korea, and China-South Korea, have deep-rooted historical grievances and hostilities, which limits what Ulaanbaatar can do.

According to the Foreign Ministry of Mongolia, the seventh Ulaanbaatar Dialogue on Northeast Asian Security convened representatives from 20 countries and 30 international organizations, and 150 people participated (some attended virtually due to COVID-19). This year’s conference included five panels: “Regional Security Challenges and Opportunities,” “Multilateral Cooperation in Northeast Asia,” “Post-Covid Regional Economic Cooperation,” “The Future of Peaceful Northeast Asia,” and “Energy in Transition.”

The foreign minister of Mongolia, Battsetseg Batmunkh stated, “In comparison to the previous six years, this year’s conference gathered more diverse participants. In other words, Mongolia is becoming more influential in promoting security dialogue and communication in our region. Moreover, it is important that not only Northeast Asia countries, but European and Western countries have begun to actively participate in the dialogue.”

This year, Australia, Canada, France, Italy, Slovenia, Turkey, and the United Kingdom all joined the Ulaanbaatar Dialogue.

Since its establishment in 2014, the Ulaanbaatar Dialogue on Northeast Asian Security has created a platform where country representatives, academics, and field experts find a working mechanism for solving traditional and non-traditional issues. These dialogues and mechanisms will then be considered to help navigate policymakers to make better decisions.

From a security standpoint, in Northeast Asia – a region without a collective defense system – the individual policies of China, Russia, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, and South Korea, are often divided into blocs, especially amid growing China-U.S. tensions. Nevertheless, Mongolia, despite its small-state status, remains a trustworthy partner with all the Northeast Asian countries. The idea of Mongolia as an active, independent player in the realm of international relations requires perpetual nourishment, whether at the bilateral or multilateral level. The Ulaanbaatar Dialogue on Northeast Asian Security is one of these foreign policy mechanisms Mongolia must continue.