NUR-SULTAN, KAZAKHSTAN: When the assistant to a wealthy businessman asked journalist Makhambet Abzhan how much it would cost to delete his boss’s name from a published article on Telegram, Abzhan told him 50 million tenge, equivalent to $107,000.

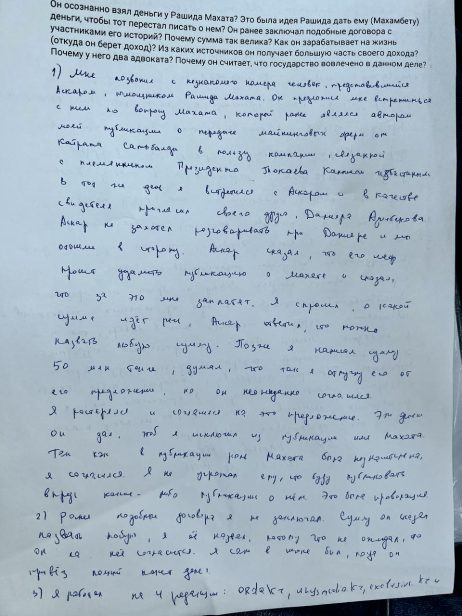

“He told me to name any number. I named it because I did not expect that he will agree to it,” Abzhan secretly wrote to this reporter from prison on Monday in answer to several questions put to him through his attorney, Tolegen Shaikov. “I thought that this [high number] will discourage him from his suggestion.”

Instead, the assistant “unexpectedly agreed,” Abzhan wrote. Abzhan wrote that he was confused but agreed to the payoff.

About 6 a.m. on July 3, the assistant called and insisted on meeting with Abzhan. When the assistant handed him a bag of money, Abzhan wrote he was “shocked.” Seconds later, police surrounded him and detained him on suspicion of extortion. The court ordered him held for two months while the Anti-Corruption Committee investigates the case.

In two handwritten pages filled with tightly curled letters, Abzhan answered questions in writing and detailed the events surrounding the payment of the 50 million tenge and his arrest. The handwriting on these pages matches other writing samples of Abzhan’s. (The writing comparison was done to refute any accusations that the answers are fake.) Until now, no one has seen this account of what led to Abzhan’s detention except Shaikov, this reporter, her editor, and her translator. This account is provided exclusively to The Diplomat for publication. Officers from Kazakhstan’s National Security Committee, or KNB, have questioned Abzhan several times about his connection to this reporter, his attorneys said.

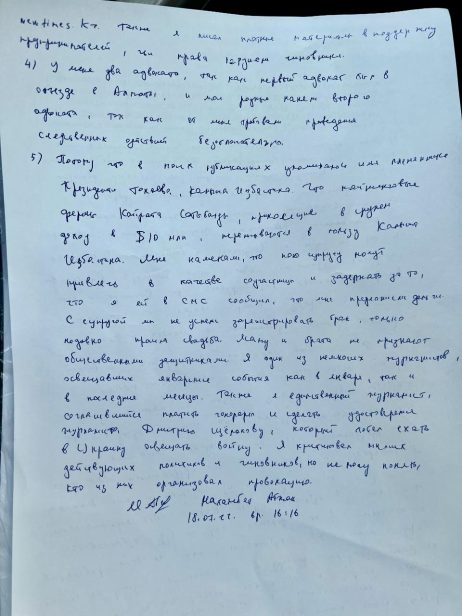

The second page of Abzhan’s handwritten answers to The Diplomat’s questions. Click to view document.

Abzhan wrote that the exchange was proposed by a man named Askar who identified himself as an assistant of Rashit Makhat. Makhat’s name was included in a published article Abzhan wrote on his Telegram channel, Abzhan News, about the transfer of crypto mining farms from Kairat Satybady, former President Nursultan Nazarbayev’s nephew, to companies connected to President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev’s nephew, Kanish Izbastin. Abzhan said he agreed to delete Makhat’s name from the article “because the role of Makhat in this publication was insignificant.” But Abzhan insisted in his written statement that “I did not threaten him that I will further publish any publications about him.”

Makhat complained to police that Abzhan had extorted the money from him. That appeal was the basis of Abzhan’s arrest, his attorneys say. Abzhan is represented by Tolegen Shaikov and Bauyrzhan Azanov. Shaikov was hired by Abzhan’s mother and Azanov was hired by Adil Soz, an Almaty-based media advocacy group, which says that Abzhan is the only Kazakhstani journalist in the country currently being detained.

Abzhan wrote that he believes the proposal from Makhat was a “provocation.” In other words, a set-up for entrapment.

Shaikov defines the situation more clearly: “This is a case of a journalist who was being unethical. But it is not a criminal case. Abzhan did not extort.”

Abzhan insists in his answers that he never previously agreed to accept money for removing someone from an article. But he admits that he has written articles for money when he believed people’s rights were being violated.

Gulzira Dusembayeva, who was married in a private ceremony to Abzhan a month ago, says that Abzhan routinely wrote articles for hire. “Sometimes when people need help, they bring money with them and he tells them a price,” she said. “He doesn’t take money from ordinary people, mostly businessmen.”

Dusembayeva said Abzhan researched the cases before he made such agreements. The cases involved “injustice or people who were in prison or when police weren’t accepting appeals.”

Dusembayeva and Abzhan are not officially married because there were problems with their registration; Abzhan was arrested before they could register the marriage properly, she said.

Dusembayeva is afraid the government will use her or try to “manipulate her” in its attempt to convict Abzhan.

“The major weak point of the case is not Makhambet or his family, but me,” she said Monday afternoon in a Nur-Sultan coffee shop. “Makhambet loves me very much, and he is worried about me. He is afraid that I am going to go prison as well. I am also afraid how I will survive in prison.”

In his handwritten answers, Abzhan wrote about Dusembayeva. He said officials had hinted that she could also be charged in the case as his “partner in crime” because he told her through a text message that he’d been approached about a payoff.

Abzhan wrote that he believes he is being targeted because he is unpopular with the current regime. Besides writing about Tokayev’s nephew, Abzhan covered the January protests.

“I was criticizing many of the policymakers and officials, but I cannot understand who was behind this provocation,” he wrote at the end of his handwritten remarks.

Azanov says the prosecutor is pressuring Abzhan to name the sources he used in his articles.

“They are saying they will exchange freedom or give him leniency if he gives them his sources,” he said. “Makhambet has high moral principles.”

Since his arrest on July 3, Abzhan’s lawyers have requested that he be let out of jail on house arrest while the case is being investigated. Those appeals were denied and Abzhan remains in detention until his trial.

Initially Abzhan cooperated with investigators, Shaikov said, and answered their questions. They allowed Abzhan to meet with Dusembayeva. Officials have since frozen Abzhan’s bank accounts and his attorneys also fear retribution. The attorneys complain that the court has not provided them access to the case files.

“The judge said it was not necessary for the attorneys to see the files in the case in order to make a defense,” Shaikov said.

Azanov says that Dusembayeva is listed as a witness in the case and shouldn’t be meeting with Abzhan. “Makhambet is spiritually vulnerable.”

When Azanov first met with his client after Abzhan was first detained, they were not given a proper meeting room or privacy. So they stood in the bathroom and continued to flush the toilet for four hours to avoid their conversation being heard by officials, whom he said were listening.

“The case is purely political,” Azanov said. “They have chosen to pursue an economic case because it appears that it is not connected with his journalism.”

Both attorneys say according to the law, police and the Interior Ministry should be investigating the charges and not the Anti-Corruption Committee, which answers directly to Tokayev.

“The Anti-Corruption Committee investigates government corruption and the wasting of government money,” explained Shaikov. “They don’t investigate average citizens.”

Shaikov said the police have searched Makhambet’s apartment, his mother’s, and that of Daniya Dilbekov, a person who was supposed to act as a witness in the money exchange. Shaikov fears his apartment is next.

Both attorneys say they fear Abzhan, who has been convicted twice before on alleged financial crimes, will be convicted in this case because of investigators’ early intervention in the case and the speed with which he was arrested. Because of the severity of the charges, Abzhan faces up to eight years in prison if convicted.

Shaikov defended his client’s “unethical” behavior of accepting money to influence a story, saying that in Kazakhstan it is hard to survive as an independent journalist. “Brave journalists are in bad financial circumstances, and it is difficult for them to make a living.”

Abzhan wrote that he also has worked for news outlets such as orda.kz, ulysmedia.kz, exclusive.kz, and newtimes.kz.

Long-time Kazakhstan journalist Saniya Toiken, a reporter for Radio Free Europe’s Radio Azattyk, says that bloggers know it is unethical to take money to write articles. “But when they are shown the money, they forget all about ethics.”

Earlier this year, Abzhan prevailed twice in cases against him. In a civil defamation case, the plaintiff withdrew the lawsuit. Following the January protests, investigators accused Abzhan of instigating an unlawful rally and insulting the police. That case was also dismissed.

In 2006, Abzhan was found guilty of financial fraud while he was running as a candidate for city council in Nur-Sultan. He was sentenced to three years in prison. In 2017, he was convicted on fraud charges and sentenced to three-and-a-half years in prison. He served two years.

“In Kazakhstan, you cannot win cases,” explained Shaikov. “The majority of cases are lost. If you ask defense attorneys how many cases they have won, they will say zero. The legal system in Kazakhstan is that that government provides all the conditions to convict a person.”

Dusembayeva says Abzhan is more upbeat about his circumstances: “He says, ‘There is a God and he sees that I am not guilty.’”