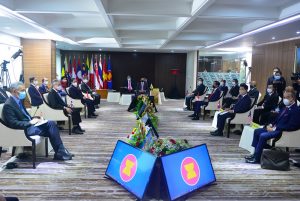

As ASEAN’s foreign ministers meet in Cambodia this week, the recent executions of four political prisoners in Myanmar by the illegal military junta should serve as yet another wake-up call for the group to change course in its approach to the deepening crisis in the country. The executions are acts of judicial barbarism committed by a military that has shown no qualms about committing any and every crime against the Myanmar population in order to cement its hold on power.

To be clear, the death sentences were handed down without fairness, by military tribunals conducting secretive trials without respect for due process. These are the conditions in which 76 other prisoners currently in Myanmar jails were sentenced to death, including two children, according to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma). The executions that took place last week, the first known in over three decades, are an ominous sign that this cruel punishment may continue to be carried out.

This is another page in the extensive catalog of atrocities that Min Aung Hlaing and his men have been committing for the past 18 months. Since the coup in February last year, at least 2,114 people have been killed by the self-styled State Administration Council (SAC), which continues shelling villages and killing protesters in a pattern of “systematic and widespread human rights violations and abuses” that may amount to “war crimes and crimes against humanity,” according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

In this context, there is no room for inaction or neutrality between the generals and the widespread popular movement opposing their rule, and all ASEAN member states should act accordingly.

Yet ASEAN’s special envoy to Myanmar, Cambodian Foreign Minister Prak Sokhonn – who visited the country only two weeks before the executions – issued a statement condemning these barely disguised political assassinations, without once mentioning the culprits – the junta leader Min Aung Hlaing and his henchmen.

Moreover, Prak Sokhonn asserts that an “extreme bellicose mood can be felt from all corners of Myanmar,” setting out a false equivalence between the criminal junta waging an all-out war against the people and a countrywide opposition movement organized to restore democracy in the country. We should not forget that the opposition to military rule only resorted to armed struggle to resist the brutal campaign launched by the military to quash an initially non-violent civil disobedience movement.

The ASEAN envoy also showed this false even-handedness when he asserted a couple of weeks ago its willingness to secretly meet the National Unity Government (NUG) of Myanmar, which opposes the junta and represents the democratic aspirations of the Myanmar people. Such secrecy stands in stark contrast with the very public meetings that Prak Sokhonn has held with the SAC, which have lent the junta a degree of legitimacy that he, representing ASEAN, is denying to the NUG.

As ASEAN chair this year, Cambodia has clearly not been up to the task of dealing with the crisis in Myanmar. Neither is ASEAN itself nor the global community above criticism. They have acted with a timidity and absence of leadership that have contributed to the Myanmar generals’ sense of impunity.

In April 2021, ASEAN member states and Min Aung Hlaing’s junta agreed on a Five-Point Consensus that called for, among other things, an “immediate cessation of violence,” and a dialogue between all stakeholders in Myanmar. It was an agreement without precedent, and it was immediately supported by other international actors such as the United States, China, and the U.N.

Yet the Myanmar military has flagrantly ignored its obligations under the agreement. It has not ceased its campaign of violence and has not taken any step towards any kind of political dialogue. Given that the Consensus lacks any enforcement mechanisms or deadlines for compliance, the junta has not faced any consequences for its failure to implement it.

With no progress on the ground, ASEAN has apparently been paralyzed, and it is deeply divided between those countries, such as Cambodia, that show an undue indulgence towards the junta, and those willing to adopt a tougher approach, such as Malaysia and Indonesia. Meanwhile, actors beyond the region are seemingly hiding behind their support for the Consensus and ASEAN to justify their lack of decisive action on Myanmar.

In order to work, the Five-Point Consensus should, at the very least, be reinforced with clear “milestones and time limits” to be met by the junta, as the Malaysian Foreign Affairs Minister Saifuddin Abdullah argued recently at an oral hearing of the International Parliamentary Inquiry on the global response to the crisis in Myanmar organized by ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights (APHR).

ASEAN can, and should, do more. For starters, the group should begin exerting pressure on the SAC by suspending Myanmar’s membership, imposing targeted sanctions and travel bans in the region on the junta and its cronies, in order to show Min Aung Hlaing and his men that they cannot commit their crimes without consequences. The chair and its special envoy must desist from making a show of its apparent even-handedness in dealing with the junta, adhere to the collective ASEAN plan, and engage openly with the NUG, as has Saifuddin.

This is a turning point for ASEAN to decide on which side of history it will place our region. Confronted by the worsening Myanmar crisis, the group cannot assert the principle of non-interference as an excuse for inaction or neutrality. Such a principle was designed to protect the sovereignty of ASEAN’s member states, but the biggest threat to the sovereignty of the Myanmar people now is its own military, which is acting as a brutal force of occupation, throwing the country into chaos with potentially destabilizing effects beyond its borders. Nor should non-interference be used as an excuse to turn a blind eye to crimes against humanity itself.

ASEAN must deliver on its responsibility to Myanmar, its people, and the region. The so-called tiger cub economies should come into their own, serve the junta with consequences that bite, and support the Myanmar people in their hour of direst need.