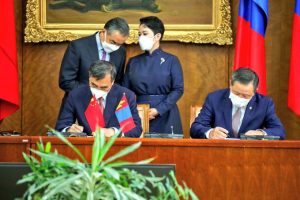

In early August, China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi paid a two-day state visit to Mongolia. There, he signed major energy agreements, including a pledge to advance the Erdeneburen hydroelectric power plant. This particular energy agreement is raising a wide range of speculation about the deepening of China-Mongolia bilateral relations but also environmental concerns – the project has the potential to damage Ramsar wetlands in northwestern Mongolia.

This was Wang’s fourth official visit to Mongolia since he became foreign minister of China in 2013. This particular visit was highly anticipated after a tremendous effort demonstrated by the Mongolian side in coping with Beijing’s draconian COIVD-19 policy. During Wang’s state visit, Mongolia and China signed the Cooperation Agreement and Plans for 2023-2024.

To jump-start bilateral economic activities, the Mongolian government prioritized major infrastructure agreements, partly to attract foreign direct investments and partly to accelerate long-stalled mega-projects, including the Erdeneburen hydroelectric power plant.

The 90-megawatt Erdeneburen hydroelectric power plant, which is planned to be Mongolia’s biggest dam, is part of Ulaanbaatar’s effort to diversify its energy sources. Mongolia’s energy dependency on Russia and China – and the constant shortages and problematic management – have caused a headache for different administrations for decades. At the same time, managing such a large hydroelectric power plant could prove difficult as well, as Mongolia has no previous experience in that regard.

In September 2021, Mongolia signed a deal awarding construction of the hydropower plant to the Power Construction Corporation of China, with the deal to be financed through a $1 billion loan from the Chinese government.

In January 2022, Mongolia’s Minister of Energy Tavinbekh Nansal stated that construction would begin in March and take just over five years. “The one remaining issue is to remove the local communities that have agricultural and herding establishments” in the affected area, Tavinbekh said. “The government is working to relocate these communities and find a likely financial repayment for their relocation.”

The government is forging ahead, but the Erdeneburen hydroelectric power plant remains controversial. It may pose significant environmental damage to one of Mongolia’s most extensive wetlands, which sustain not only the local community but also migrating animals and protected animals such as snow leopards. Wetlands act as a big sponge that collects and removes environmental toxins. The removal of wetlands can cause a cascade of environmental failure.

Moreover, even on the topic of management, the sustainability of such a large hydropower plant is also questionable, given Mongolia’s previous failure to pursue hydroelectric power plants as alternative energy.

One prominent case is the Egiin Gol Power Plant, which initially began in 1991 and acquired Chinese funding but faced environmental opposition from Russia. After 16 years of back-and-forth and wasted efforts and time, it was finally discontinued in 2007.

The Erdeneburen hydroelectric power plant, although promising and a potential game-changer, does not have the public’s confidence. The underlying issue is precisely the same as Egiin Gol: environmental concerns. It doesn’t matter if the Russians brought up the environmental issue or Mongolian environmentalists brought it to light. These issues need to be publicly addressed and discussed.

In an opinion piece published in June, Mongolian environmental activist Sukhgerel Dugersuren wrote a thorough report on the potential damage the Erdeneburen hydroelectric power plant could pose to the native species in that region. She concluded that PowerChina – the engineering corporation that would be executing the dam work – is known for “rapid dam-building” and for high-quality construction.

As Mongolia transitions to hydroelectric energy – something Mongolia is unaccustomed to, considering its extreme distance from a large body of water – the last thing the country need is to build a dam quickly and then spend decades fixing it. Hence, it is essential for the government and its agencies to consider and discuss all aspects before committing to destroying a vast area of untouched landscape.

According to Sukhgerel, “[A]s of 2 June, construction has not started: the relevant authorities in China are hesitating since local communities communicated their concerns via the embassy in Mongolia.”

Popular opposition to such a large power plant is not surprising. Destroying a vast area of natural habitat will face popular animosity in Mongolia. This public opposition is not new, nor is it unique to the Erdeneburen project.

For one, throughout different administrations, Mongolia’s government has often rushed to attract foreign direct investment without meticulous research and plans for allocating financial and capital resources.

Second, when a mega-project proposal or agreement is underway, the government repeatedly overlooks or neglects the local communities’ concerns, causing widespread opposition. Most of the concerns center on the destruction of certain sacred lands and natural habitats. One major case involved previous efforts to save Noyon Uul from exploitation in a mining project.

While the need to accelerate Mongolia’s economy and diversify its energy sector is crucial, the government should not turn a blind eye to environmental issues that can damage the country’s largest wetlands.

Yet the current government of Mongolia has been proactive in pushing major infrastructure deals with Beijing, including not only the Erdeneburen project but also major railways.

Prime Minister Oyun-Erdene Luvsannamsrai’s government is seeking to align Mongolia’s infrastructure development plans with Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative. The logic behind such a strategy is that Beijing has always been open to cooperate with Mongolia’s development sector and acted as a major financier. Oyun-Erdene has previously mentioned the economic opportunities offered by China number of times as part of his government’s “New Revival Policy,” a post-COVID economic recovery plan.

However, skeptics of the current government have voiced worries about the government’s over-commitment to mega projects. The deepening of Mongolia’s dependency on China is also a concern.

In the grand scheme of themes, since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Mongolia’s foreign policy has been in murky water. While Ulaanbaatar prioritizes its traditional bilateral relations with Russia and China – for obvious geopolitical reasons – the significance of having continued a strong connection with rest of the world became ever clearer.

This was a busy summer for Mongolia. Ulaanbaatar hosted multiple international conferences and multiple high-level visits of foreign officials. Following Wang Yi’s state visit, U.N. Secretary General Antonio Guterres came to Mongolia and participated in a tree planting ceremony with Mongolian President Khurelsukh Ukhnaa.

Despite these high-level visits and international commitments to climate change and environmental investment, the government must address the issues raised by Erdeneburen hydroelectric power plant.

Given Mongolia’s ecosystem, the tiniest wetlands play a significant role in sustaining the country’s vast untouched landscape. In short, at a time when the president has pledged to plant 1 billion trees, the other side of the government cannot be negligent and duplicitous about other environmental concerns.