As a visiting fellow at Trinity College in the department of geology, Abdul Aziz Mohibbi – one of the co-authors of this piece – is now far from the office that he occupies as chancellor of Bamyan University in the Afghan province of the same name. Still, he remains connected to his students as best he can. He has tried a variety of online platforms for continuing to teach his course on “Social Forestry,” but ended up primarily relying on Instagram, since it could handle the files he wanted to share and because it was difficult for the Taliban to monitor.

At the same time, Noah Coburn – the other co-author – was developing an online course for American University of Afghanistan and other Afghan students through Bennington College. This course connected students in Afghanistan with those in six other countries to reflect on the history of Afghanistan and the ongoing crisis. Both courses allowed those students, still studying in now Taliban-controlled universities, the ability to think critically and debate openly, something that now seems impossible to many.

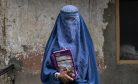

As both of these initiatives suggest, while much of the international community has been focused on the plight of girls who are banned from secondary school, those students a few years older, both male and female, who are trying to continue their university educations are also struggling. Many faculty have fled the country and those that remain are often no longer receiving their promised pay, while students have to contend with shifting Taliban restrictions on dress, freedom of speech, and, particularly for women, travel.

Already, a year into this new Taliban regime, the international community has struggled to find a coherent response to Taliban violations of human rights. While the outcry about the exclusion of girls from secondary schools led to the suspension of World Bank programs in the country, there have been far fewer conversations about the fate of higher education outside of a few donor circles.

In response to this, in July, the Hollings Center for International Dialogue brought together members of Afghan civil society, administrators, and faculty from public and private universities inside and outside Afghanistan, as well as Ministry of Higher Education officials and specialists from international organizations, to discuss the ways in which Taliban policies have been rapidly eroding the strides that were made in Afghan higher education over the past 20 years, and how best to respond.

As the chancellor of Bamyan University, Abdul Aziz Mohibbi had overseen large growth. The school had approximately 170 faculty members and 7,600 students in 34 different departments when the Taliban returned last August. While many faculty members in Afghan universities were criticized for being under-credentialed, Mohibbi had worked with a variety of international organizations to get 40 of his faculty members enrolled in mostly Ph.D. programs abroad, which they could work on remotely while continuing to teach at the university. The university had partnerships with many universities – some in Europe, but others in neighboring countries like India and Iran, where it was easier to send faculty and collaborate on regional issues of scholarly interest.

He also realized that the university was only as strong as its incoming students and had partnered with the director of education in Bamyan to write a proposal to the Ministry of Higher Education and Ministry of Education for upgrading the teachers’ local secondary schools to prepare students for university. By 2020, 1,100 teachers from the province, most of them women, were taking courses through the university.

All of this was part of a general growth in Afghanistan’s higher education sector between 2002 and 2021. With just seven institutions in 2001, all of which were public, by 2020, the higher education sector in Afghanistan had grown to 39 public and 128 private universities. In 2001, there were only 8,000 students enrolled in Afghan universities, and by 2020 there were almost 400,000. And while problems with equity and access persisted, particularly for women and minorities, 110,000 of those enrolled were women, up from essentially zero in 2001. True, there were concerns about the quality of some of the new institutions in this rapidly expanding sector, but the Ministry of Higher Education had worked to improve accrediting processes and ensure the quality of these schools.

When the Taliban arrived in Bamiyan, the capital of Bamyan province, last summer, shortly after the fall of Kabul, everything changed. The new government sent a “representative” from the Ministry of Higher Education to oversee the university. Mohibbi was asked to stay on, but this was for appearances’ sake; the new Taliban representative was now the only decision-maker. The representative brought with him a militia of bodyguards and he hired former Taliban fighters across the college. Women were excluded from classes initially, and students and faculty were soon censoring themselves in and out of classes, fearing Taliban punishment.

After three months of this, Mohibbi no longer felt sure he could keep his family safe, and, using some academic connections, he fled the country. Now, he estimates that about 20 percent of his faculty did likewise. Unfortunately, it was often those who were most well-established or were in international Ph.D. programs that had the connections to leave the country. So the 20 percent of the faculty who left were the best of his faculty. Few of his students had the means to leave the country, but the ensuing economic collapse has meant that more and more students are dropping out to attempt to earn money for their families.

There are several ways that Mohibbi and others are working to support the students that remain in Bamiyan, but they face many difficulties. The collapse of the economy means that many students have had to get jobs to provide for their families. Women remain fearful of the erratic Taliban police and their inconsistent and often violent enforcement of restrictions, particularly on how women dress and their ability to travel.

There are international programs that are attempting to help some of the scholars and students that remain in Afghanistan, which were highlighted at the recent Hollings Center meeting. Most international partnerships that were set up in the past 20 years have been frozen, but some do continue. The American University of Afghanistan is continuing to recruit students online and Mohibbi has been working with the Yunus Center at the Asian Institute of Technology in Thailand to set up a Master’s program for students from Afghanistan.

Still, there is much more that could be done. Taliban control is uneven across the country and areas that were historically the most resistant to the Taliban, particularly in the center and north of the country, often have more space to operate than in other areas. More programs could focus on these areas. Faculty members in Afghanistan want research support that they could get from universities in neighboring countries. Students are in dire need of financial support for their studies, which could be provided without directly working through the Taliban authorities.

There is not enough international focus from the donor or academic community on these programs, and many of them have immense logistical challenges even beyond Taliban restrictions, which many of the programs attempt to skirt by remaining primarily online. For one, internet access Afghanistan (not to mention electricity) remains unreliable in many parts of Afghanistan. Even before the Taliban return, during COVID-19, Bamyan University had experience with other online platforms, but the fact that many of these are hard to access without high speed internet and most are in English meant that few students could really take advantage of these resources.

The February reopening of gender-segregated university classes brought opportunities but also new challenges. There are well-justified concerns that the Taliban reopening of universities will simply create more opportunities for radicalization and the teaching of Taliban orthodoxy. Already the Taliban have increased the national requirement of classes focused on “Islamic Civilization” from one or two, depending upon degree, to 24. These courses are replacing other vital courses in all disciplines. And, of course, in a few years, if girls are still banned from secondary schools, there will be no women in Afghan universities.

The long-term future of education in Afghanistan is dark. The Taliban have ordered that every district have a government madrassa. Faculty and students in fear of the authorities are increasingly self-censoring. Those in the classroom fear being reported by informants. Still, there are thousands of Afghan faculty and hundreds of thousands of Afghan students who want more than this, and even small efforts, like forestry courses on Instagram, can go far in providing some hope of real scholarly engagement.