The Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) is a large-scale economic cooperation initiative between several former Soviet states. It aims to create a shared market similar to the European Union and intends to accomplish this by coordinating economic agendas, removing non-tariff trade barriers, and aligning the laws and regulations of its five members — Russia, Kazakhstan, Belarus, Armenia, and Kyrgyzstan. Uzbekistan is an observer state, while neither Tajikistan nor Turkmenistan is a member.

The EAEU is also in the process of negotiating free trade agreements with a number of countries, including India, Egypt, and Thailand, and has signed such agreements with Iran and Vietnam. The EAEU’s trade turnover surpassed $73 billion last year, with the Russian ruble serving as the primary currency, accounting for 72 percent of all payments.

However, the economic impact of the union on the Russian economy is minor, and Russia’s trade volume with the EAEU is significantly lower than its trade volume with the rest of the world.

On the other end of the spectrum, it is abundantly clear that the EAEU does not provide sufficient economic benefits to Kazakhstan, the union’s second-largest economy. Although the trade volume between Kazakhstan and other EAEU members has not increased significantly since 2014, the country has become more reliant on Russian exports and imports. In Kazakhstan, increasing tariff rates for non-EAEU members while allowing duty-free imports from Russia has resulted in trade diversion and negative economic consequences for the country.

Furthermore, Kyrgyzstan has one of the highest remittance-to-GDP ratios in the world, and the number of Kyrgyz immigrant workers going to Russia increased significantly in 2014. As a result, the government became more susceptible to Russian demands to join the EAEU and did so within a year. So far, Uzbekistan appears to be content to remain outside the union, but Tashkent did attain observer status in 2021.

The Russian mindset behind the union’s formation was ultimately driven by geopolitical concerns rather than economic ones. With the EAEU, Russian President Vladimir Putin arguably sought to reestablish Russia’s dominance in Moscow’s traditional sphere of influence, which had been lost with the disintegration of the Soviet Union. Based on the motivations of other members, a union with Russia provided political support, cheaper energy, and security guarantees. This is demonstrated by Russia’s intervention in the Second Karabakh War in favor of Armenia, unconditional support for Alexander Lukashenko in Belarus, and the recent Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) intervention in Kazakhstan.

However, recent international sanctions actually rendered the EAEU far more economically beneficial to Russia than ever before. Kazakhstan, for example, has been conducive to avoiding sanctions and importing banned products. As it is, Russia needs the EAEU more than ever and will do its best to keep these countries on its side.

This is exactly why, following an EAEU meeting in Yerevan, Armenia, in October, Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin emphasized the need for a unified oil, gas, and electricity market among the member countries due to hikes in energy prices. Mishustin highlighted that creating such a common energy market will benefit all members and shield their citizens from rising energy prices.

Will such incentives keep Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan consolidated within the union and attract Uzbekistan to consider pursuing full membership? While Russian political and military influence is dwindling, will a Russian-designed economic union survive in changing geopolitics? The answer comes partially down to the Central Asian governments’ unique stances and it’s helpful to look at other Russian-dominated regional organizations, too.

For example, during the most recent Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) meeting, the worsening border dispute between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan was very unsettling for Putin, as both countries are members of the CSTO. Many in Bishkek accused Moscow of backing Tajik President Emomali Rahmon despite Moscow’s inability to take action and calm the conflict. As a result, Kyrgyzstan refused to participate in the latest CSTO military drills in Tajikistan. The refusal to participate is a clear demonstration of Moscow’s dwindling influence in Central Asia.

As a result of Russian leaders’ irredentist rhetoric and their implied territorial claims over northern Kazakhstan, many Kazakhs view Russia with suspicion. Even after the CSTO intervened in Kazakhstan in January 2022, seen as clear Russian backing of President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, the Kazakh government has pursued a more vigorous opposition than expected to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

However, even if the Kyrgyz and Kazakh governments seem less willing to pursue more integration with Russia and Uzbekistan never joins the EAEU, Russia is too powerful for any Central Asian leader to overlook. At the end of the day, the capacity of Central Asian states to fend off geopolitical risks from Russia is limited, and an impending attempt to decouple from Russia will almost certainly have profound implications.

In such a situation, public opinion matters, alongside government willingness to heed it. So, what does the public think?

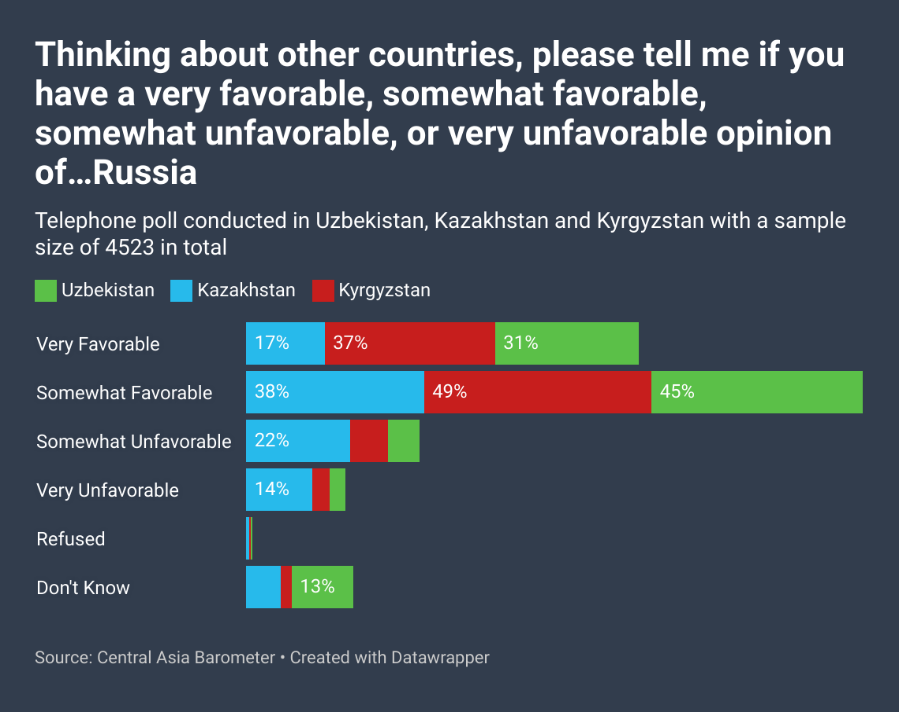

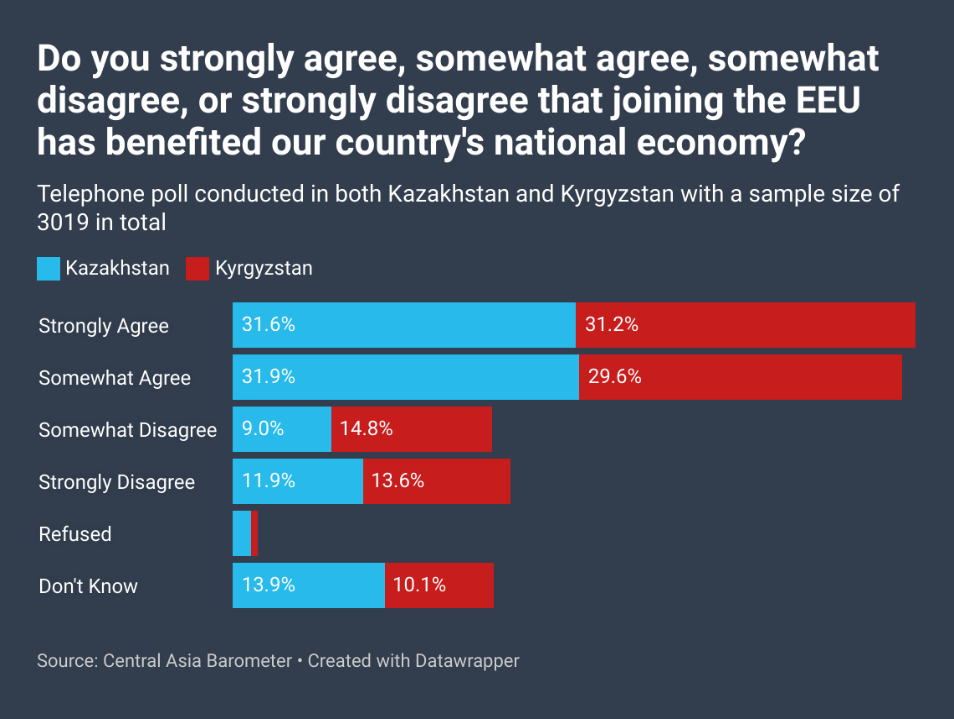

A Central Asia Barometer (CAB) poll conducted last May and June suggests that 63.5 percent of Kazakhs and 60.8 percent of Kyrgyz believe that joining the EAEU benefited their national economy. Also, it shows that public intimacy with Russia is still high in the region: 85.7 percent of Kyrgyz, 76.4 percent of Uzbeks, and 55.2 percent of Kazakhs have a favorable opinion of Russia.

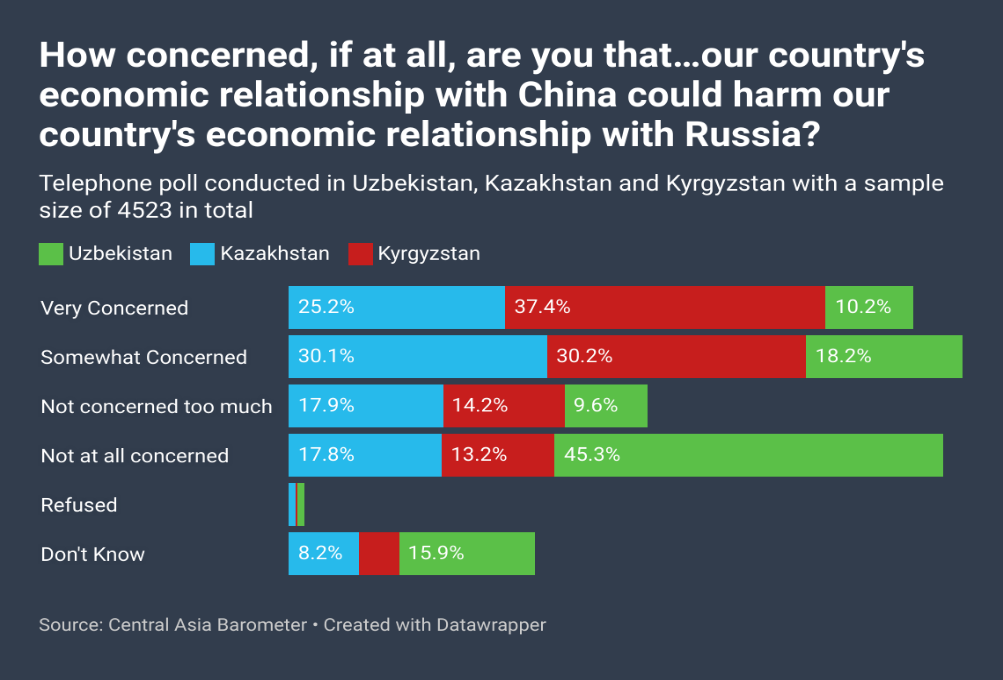

However, a more striking point is that most people in these three Central Asian countries think that Russia will hit them hard due to their improving economic ties with China. 67.6 percent of Kyrgyz and 55.3 percent of Kazakhs believe that better economic relations with China could harm their economic relationships with Russia. In Uzbekistan, a non-EAEU member, this ratio is remarkably lower, at 28.4 percent.

Affinity toward Russia at the public level is still very high, but Russian culture and language are losing their dominant position and must compete with different worldviews to win the hearts and minds of younger Central Asians. These highly-diverse and broad-minded generations are shaped by inspirations from Europe, Turkey, China, or the United States.

Affinity toward Russia at the public level is still very high, but Russian culture and language are losing their dominant position and must compete with different worldviews to win the hearts and minds of younger Central Asians. These highly-diverse and broad-minded generations are shaped by inspirations from Europe, Turkey, China, or the United States.

Russia has little to offer economically; the unanticipated consequences and rising costs of reliance on Russia will force these governments to diversify their diplomatic ties more than ever. However, this shift does not necessitate that these governments will seek stronger ties with the West or adhere to the conventional paradigm of multivector diplomacy. Instead, Central Asian leaders may be inclined to establish closer ties with China and Turkey. Both countries can provide better economic opportunities to Central Asians. China is the most important economic actor in the region; it is the largest trade partner to Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan by imports and Turkmenistan by energy exports.

While Russia is distracted in Ukraine, Turkey is seeking stronger economic cooperation with Central Asia, too. In this regard, the Turkic Investment Fund was created following the last summit of the Organization of Turkic States (OTS) in November 2022. The fund aims to increase economic cooperation within member countries by supporting small and medium enterprises in various industries.

Russia’s weakness in providing economic prosperity through the EAEU and increasing Chinese and Turkish economic presence in the region may also feed the weakness in Russia’s ability to be a security provider through the CSTO. If Russia’s primary security provider role in the region begins to be questioned, entrenched Russian dominance will weaken. If this occurs, it would be unrealistic to expect the EAEU to expand and have a voice in the future of Central Asia.