Argentine President Alberto Fernandez is entering the final stretch of his term in office. Among the many failures his government accumulated over the last three years is a record of failed diplomacy with China. There are ample arguments to buttress the claim that Fernandez lacked a coherent and consistent foreign policy, particularly when it comes to Beijing.

The Argentine government does not seem to realize the geopolitical paradigm shift implied by COVID-19 and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, especially with regard to energy, food security, and defense, and what this implies for relations with China and other global powers.

The Kirchnerist government’s diplomacy has been characterized by improvisation, marked ideological bias, and permanent oscillations in relations with third countries (including the United States and Russia, to mention just two examples alongside China). In this context, the strategic relationship with China also foundered, and is now in a state of virtual stagnation, which is very negative for both sides.

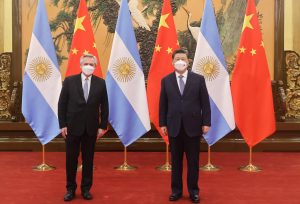

From the very beginning of his term in office in December 2019, Fernandez made big promises to China that have yet to become reality. The president even traveled to Beijing in February 2022 and endorsed the controversial Belt and Road Initiative, signing a score of memoranda full of grandiose projects worth more than $23 billion. Many of these projects are not new, however, as they have been dragging on in Sino-Argentine relations for a decade.

Argentina has a long record of failing to follow through on previously agreed-upon projects – a source of frustration from the Chinese point of view. The most paradigmatic case is that of the Atucha III nuclear power plant, which first appeared on the short list of projects that China would finance in Argentina in 2014, during an official visit by Chinese President Xi Jinping to Buenos Aires.

Then President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner herself publicized the nuclear plant deal as an achievement on her personal website. The now imprisoned Julio De Vido, who was minister of federal planning at the time, had been put in charge of negotiations with the China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC), whose main interest was to operate its Hualong One technology outside China.

The nuclear power plant project between CNNC and its Argentine counterpart, state-owned Nucleoelectrica SA, made no concrete progress during Kirchner’s second term, nor during the presidency of Mauricio Macri, who twice renegotiated the agreement. Memoranda, cooperation agreements, and even a few commercial contracts were signed, but these have been canceled due to lack of financing, as in almost all the projects that never got off the ground.

In terms of infrastructure, there are dozens of other projects that have been frustrated. Several also date back to Kirchner’s first visits to China and saw unsuccessful resurrection efforts by Fernandez’s government. These include the Chaco-Corrientes bridge, the Vaca Muerta gas pipeline, the Manuel Belgrano II thermoelectric plant, AySA’s South Underground River, the logistics center in Tierra del Fuego, dredging projects, high-voltage electricity connections, and improvements to railway branches.

To this must be added the standstill in central works that already have Chinese financing, such as the Santa Cruz dams, China’s most important infrastructure project in Argentina. A recent Chinese disbursement of $212 million attempted to give a new lease of life to this project, which has been plagued by systematic defaults on Argentine payments, structural problems, lawsuits, and trade union crises, among other ills from 2013 to date. It took a decade for the first turbine of the project, which should have been completed by 2019, to arrive in Argentina. Should it ever be completed, it will merely mark the beginning of a new chapter in this drawn-out story: More than 3,000 kilometers of extra-high voltage lines needed to connect the dams to the main electricity consumption nodes.

Another area loaded with frustrations and projects that never materialized is the oil sector. At a time when Vaca Muerta is presented, even by the government itself, as the goose that lays the golden eggs, China has been left out of the business. First came the exit of Sinopec from Argentina in 2020, after suffering severe trade union conflicts in the province of Santa Cruz (where the Kirchner family consolidated its power).

And then there were infrastructure works such as gas pipelines and liquefaction plants that came to nothing. The space that China hoped to occupy, both in production and construction, with companies such as PowerChina at the forefront, does not seem to exist now.

But it was not only in infrastructure and energy that there were drawbacks in the relationship. Many central issues on the bilateral agenda did not materialize or were not resolved. To mention a few more of the most famous cases: the pork agreement, the purchase of JF-17 fighter jets, the problem of illegal fishing in the Argentine Sea by Chinese vessels, and the activation of the bilateral treaty to eliminate double taxation, signed by both parties in 2018. These are just some of the main pending issues.

The balance sheet for Argentina of this failed foreign policy is very negative. Important Chinese investments have come to a standstill or, at the very least, are not advancing at the expected pace, both in energy and in transport and telecommunications. Perhaps the only sector that has managed to take off significantly is mining, driven by the growing interest of Chinese companies in lithium. Also of note is the expansion of the Cauchari solar park in Jujuy. But there is not much else to celebrate.

Since 2019, there have been no new major financing deals from Chinese banks in Argentina, which is in line with China’s role in the region. Xi Jinping’s administration has shifted its strategy toward Latin America. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, it has only made progress in a few key areas in countries with closer relations to Beijing, as shown by the mergers and acquisitions in energy companies in Chile (with has signed an FTA with China) and Brazil (a fellow member of the BRICS grouping).

While Chinese investment – or, more accurately, financing, because there are few cases of direct investment by Chinese companies in Argentina – is stagnating, the trade deficit continues to grow. The Macri government managed to reduce this chronic deficit in the relationship with China to $2.441 billion by the end of 2019, while the government of Alberto Fernandez returned it to record levels – above $9 billion in 2022. What is worse, the trade volume is not increasing. It has been stabilized for almost two decades, with little diversification and huge opportunities squandered. In 2020, the Fernandez government even went so far as to ban meat exports to try to curb inflation.

Foreign Minister Santiago Cafiero, in his most recent communication with his new Chinese counterpart, Qin Gang, “emphasized the importance of promoting a more balanced and diversified bilateral trade, and also stressed the need to speed up the process of opening up the market for Argentine products,” according to the official communiqué. Of course, Cafiero avoided referring to the productive reprimarization that the sale of soya beans to China (still Argentina’s main export product) entails, compared to the sale of oils and pellets to India and the ASEAN countries, for example.

On the other hand, Argentine products, despite the opening of markets, have problems competing in global trade, mainly due to internal economic and financial restrictions, and also because of the scarcity of commercial agreements that Argentina has signed. In this regard, Fernandez has already made clear her opposition to a possible Mercosur-China agreement.

Finally, there is the currency swap. In reality, the word “swap” is a misnomer from the perspective of a country that has no currency, such as Argentina. The swap is nothing more than a sovereign loan from China in yuan, convertible into dollars at a high financial cost. In fact, the swap was renewed and has just been extended by some $5 billion, with the aggravating factor that China granted Minister of Economy Sergio Massa the guarantee to freely use this extension to operate in the foreign exchange market. In total, the swap is already around $23 billion.

Are these shortcomings all China’s fault? Clearly not. Argentina has become one of the most closed economies in the world, with an absolutely hostile context for production, foreign investment, and foreign trade in general, regardless of the country concerned.

For its part, China seems to maintain unlimited reserves of patience in dealing with Argentina. There continue to be friendly gestures from China, both political and economic – surely with the aim of trying to keep afloat one of Beijing’s most important but also most complicated relations in Latin America. Most likely, China’s government has its sights set beyond December of this year.

The article was first published in Spanish by Diario Perfil. Read the original piece here.