Nine Southeast Asian nations have voted to support the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA)’s latest resolution condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and calling for the country to withdraw its forces.

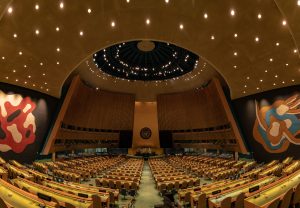

The vote, which took place on the eve of the anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, saw 141 member states support a resolution calling for “just and lasting” peace. Thirty-two countries abstained from the vote – among them, China and India – while just seven nations – Russia, Belarus, North Korea, Syria, Mali, Eritrea, and Nicaragua – voted against it.

The resolution “reaffirms its commitment to the sovereignty, independence, unity and territorial integrity of Ukraine within its internationally recognized borders, extending to its territorial waters.” It also “reiterates its demand that the Russian Federation immediately, completely and unconditionally withdraw all of its military forces from the territory of Ukraine within its internationally recognized borders, and calls for a cessation of hostilities.”

Nine of Southeast Asia’s 11 nations voted in favor of the resolution, with just Vietnam and Laos choosing to abstain. This was little surprise, given that they are one-party communist states who have had longstanding relations with Russia and before it, the Soviet Union.

Myanmar, meanwhile, has supported every resolution that the U.N. has passed about the Russian invasion, though it is worth noting that the country’s U.N. mission remains under the control of the opposition National Unity Government. (If it had the chance, one would expect the military junta to join the seven nations who voted against.)

Yesterday’s vote was mostly consistent with how the region has voted on the major UNGA resolutions condemning the Russian war of aggression, though the April 7, 2021 vote on whether to expel Russia from the U.N. Human Rights Council enjoyed much less support in the region. Just three nations – the Philippines, Timor-Leste, and Myanmar – voted to support that resolution, while six nations abstained, and Vietnam and Laos voted against.

Other than that, the only significant outlier was Thailand’s puzzling decision to abstain from last October’s resolution condemning Russian President Vladimir Putin’s annexation of territories in Ukraine. At the time, some (including this author) suggested that this vote might have been influenced by Bangkok’s desire to ensure Putin’s attendance at the APEC Summit in November.

The general regional opposition to the Russian actions in Ukraine should not be taken as a sign that they are preparing concrete measures to punish Moscow. Of the 11 Southeast Asian states, just one – Singapore – has joined the international campaign of sanctions against Russia. As Zachary Abuza of the National War College in Washington, D.C. noted on Twitter, “the voting record” of most Southeast Asian states “is far better than the actual record.”

A year into what looks increasingly likely to be a protracted war in eastern Europe, Southeast Asian nations continue to stand aloof. This is likely less due to fear of ostracizing Russia, a nation whose influence and prestige (at least outside Vietnam and Laos) remains limited. It stems rather from a regional concern about the global impacts of a protracted struggle, and a general desire to stand above the geopolitical competition. This in turn suggests that for all the region’s principled opposition to the Russian war, the predominant Western depictions of the war as a grand ideological clash and an epoch- and world order-defining event continues to be viewed with some skepticism.