Xi Jinping’s visit to Myanmar in January 2020, the first by a Chinese president in almost 20 years, symbolically endorsed the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC). This marked the culmination of an intense phase of activity by China in Myanmar, reconstituting Sino-Myanmar relations in the wake of Myanmar’s putative democratic transition.

The fruits of the plan were short-lived. Within a few months of Xi’s historic visit, the China-Myanmar border was closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic and less than 13 months later, on February 1, 2021, Myanmar’s military staged a coup d’état.

In the wake of the coup, China has once again recalibrated its approach, siding firmly with the military and adopting a peripheral strategy to investing in projects under CMEC.

CMEC’s Origin

Myanmar’s core strategic importance to China is its access to the Bay of Bengal and wider Indian Ocean. China transfers oil and gas via pipelines across Myanmar to Yunnan province, partially mitigating its concerns about its heavy reliance on the narrow Malacca Straits. If CMEC succeeds, China will be able to shift manufacturing from its coastal areas to its southwestern provinces as part of a bid to avoid the middle-income trap. Transporting goods through Myanmar provides shorter routes to markets in South Asia, East Africa, West Asia, and Europe and opens the Myanmar market to all Chinese goods and services while allowing China to efficiently import raw materials from Myanmar and beyond.

CMEC was not one of the original economic corridors of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, but was a smaller part of the much more ambitious Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor proposed in 2013 by Premier Li Keqiang. When it became clear this was unlikely, due to a lack of desire on India’s part to participate amid rising tension with China, China’s foreign minister proposed CMEC as a standalone economic corridor in 2017.

After taking office in 2016, the National League for Democracy government handled negotiations at a cautious and measured pace as Myanmar emerged from a long period of economic stagnation. During this period the government was particularly focused on avoiding unsustainable debt. Aung San Suu Kyi, who attended the Belt and Road Forums in Beijing in 2017 and 2019, ultimately agreed to nine “early harvest” projects, from a Chinese proposal of 30 projects, in April 2019.

The nine CMEC projects, if implemented, promised to transform Myanmar’s economy. These projects were to form an upside-down Y shape on the map of Myanmar. The top branch began at Muse, Myanmar’s primary border crossing with China. This headed south to Mandalay, at which point two branches were to split off, one heading south to the commercial capital Yangon, the other southwest to Kyaukphyu on the Bay of Bengal. Projects included upgrading and creating new Border Trade Zones, multiple new industrial zones, a deep-sea port and Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in Kyaukphyu, a new city for more than 1 million people to the west of Yangon on a floodplain, and the connection of these various projects with new railways and highways.

After the Coup

The February 2021 military coup upended years of diplomacy between Myanmar and China. The people of Myanmar overwhelmingly rejected the coup and demanded that the military respect the results of the November 2020 election and return the country to democracy. The military ignored the wishes of the people and set up the State Administration Council. Due to the military’s intransigence, Myanmar has descended into civil war as a wide range of civilian, pro-democracy activists, militias, ethnic armed groups, and the National Unity Government resist military rule.

Having invested so much in relations with Aung San Suu Kyi’s democratically elected government, China hedged its position in the early post-coup days. On February 15, two weeks after the military takeover, China’s ambassador to Myanmar stated that the current political situation was “absolutely not what China wants to see” and dismissed social media rumors of Chinese involvement in the military coup as “completely nonsense.” However, China blocked a U.N. Security Council Statement condemning the coup, and on February 23, a Chinese official asked the military for extra security for the oil and gas pipelines and for better media coverage.

Myanmar’s military wanted Chinese support for the coup, but its priority was taking control within Myanmar. With the bureaucratic machinery firmly under military control, the CMEC Joint Committee’s commitment to involve the people of Myanmar in CMEC was revoked in March.

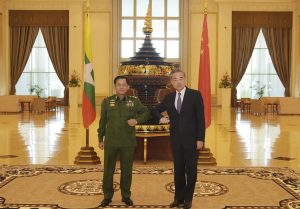

Relations between China and the military junta warmed in the months following the coup. In June 2021, China’s then-foreign minister, Wang Yi, met his junta counterpart. In August, China delivered a refurbished submarine to Myanmar’s navy. Wang’s visit to Myanmar in April 2022, during which he announced that “no matter how the situation changes, China will support Myanmar,” was the definitive sign of a return to business as usual.

In the decade before the coup, Myanmar’s leaders could balance Beijing’s demands by playing foreign actors’ interests against each other and inviting other investors to participate in projects. Post-coup, with the economy devastated and foreign direct investment in free-fall, China now holds most of the cards and can control which projects it implements and when. The Myanmar military and the bureaucracy it controls must largely fall in line.

With China able to implement projects largely of its own choosing, it is possible to discern a clear pattern and strategic drive behind the approved projects that are moving forward. All these projects have one thing in common; they are all located in the geographical periphery of Myanmar. These areas are the calmest and/or border China.

Although the projects are moving forward at very different rates they include the deep-sea port, SEZ, and power plant at Kyaukphyu; two border trade zones (one of which is approved, the other still in the planning phase); the Mee Ling Gyaing LNG terminal in Ayeyarwady Region on the Bay of Bengal; and possibly the New Yangon Development City, though this remains at the planning stage. Projects that have stalled or stopped include the railway from Muse to Mandalay, related road systems, and multiple industrial zones planned for construction along the transportation routes.

Emblematically, the Myitsone Dam project in Kachin State remains frozen, though it continues to harm communities still displaced more than a decade after the project was officially suspended. In the immediate post-coup period, there were concerns that the dam project could restart. As part of the military’s charm offensive toward China, the head of the armed forces and leader of the SAC, Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, made pointed comments that hydropower would be an important part of Myanmar’s energy mix in the future. So far, at least, China does not seem to have any plans to restart the project, though uncertainty remains.

Kyaukphyu has remained relatively stable since the coup due to the complex political arrangement between the local ethnic armed group, the Arakan Army, and the military. Necessary for both the deep-sea port and SEZ, a Chinese-backed modular 135 MW gas-fired power plant – installed entirely after the coup – began operating in October of last year. The completion of this project demonstrates that China is still committed to pushing CMEC projects to completion if and when local conditions allow.

The deep-sea port at Kyaukphyu is moving ahead, albeit at a slower place. China’s state-owned company CITIC, which is overseeing the whole deep-sea port project, contracted a Myanmar company, Myanmar Survey Research, to undertake an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) of the port. This work is in progress. While EIAs are required by Myanmar law it is interesting that CITIC decided to have one conducted before moving forward, because they are clearly not required to do so by the government, and none was done for the Kyaukphyu power plant.

Citizens and civil society groups have not remained passive in the face of these large-scale infrastructure projects, which threaten their land, environment, and livelihoods. Despite the risks of being seen to oppose anything sanctioned by the military, the public has remained highly skeptical of these projects. While all communities would welcome decent well-paying jobs, they know that it is far more likely these benefits will not be made available to them, and that they will be left with the negative impacts.

In Kachin State, villagers have pushed back on Chinese rare earth mining close to the border. Communities displaced by the Myitsone Dam continue to demand that the project be definitively canceled. In other areas people have tried to use the law to secure better outcomes for themselves and their communities. In Kyaukphyu, communities have been using environmental regulations to push Chinese companies to stop the environmental damage caused by the oil terminal on Maday Island. Fishermen and farmers have engaged with the EIA process and protested when they have been ignored.

The Future of CMEC

Myanmar’s political future is uncertain. Multiple forces enjoying popular legitimacy now oppose military rule. Whether they can prevail or hold the military in a protracted stalemate is very much an open question. The most likely outcome in the short and medium term is continued violence, oppression, economic collapse, and chaos in which no side enjoys any lasting victories.

China’s plan seems clear. It intends to remain the indispensable player, so that whatever combination of political forces eventually prevails will be indebted to Beijing. While the Chinese government continues to support the military, it is simultaneously cooperating and working with many ethnic armed organizations and other forces within the country.

China will continue to build key infrastructure around Myanmar’s periphery under CMEC. It will wait to connect it together by road and rail when the country is more stable, regardless of the cost of that stability to the people of Myanmar.