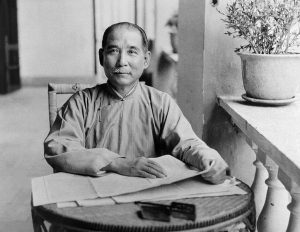

On March 30, 1940, 83 years ago this week, the wartime Japanese occupiers of China established a new “Reorganized National Government of the Republic of China,” otherwise known as the RNG, in Nanjing, the former capital of the Republic of China. At the head of this puppet government the Japanese were delighted to be able to install no less of a personage than the former head of the Chinese Nationalist Party, Wang Jingwei. Wang had been a protégé of Sun Yat-sen (the father of the Chinese revolution that overthrew the Qing Dynasty), and had shared power with Chiang Kai-shek, the military leader of the Nationalist Party who rose to power after Sun’s death in 1925.

Wang had until that time had a remarkable career. His interest in the influence of Western thought in Japan led him to join Sun’s Tongmenhui Party, whose goal it was to overthrow the Qing Dynasty. Before that goal was achieved in 1911, Wang himself plotted to assassinate the Prince Regent of China, Zaifeng, Prince of Chun. (Chun is better known in history as the father of Pu Yi, the last emperor of China.) Wang Jingwei’s death sentence for that attempt was commuted to life imprisonment by Prince Chun himself.

Fortuitously for Wang, the entire Qing imperial house was ousted shortly thereafter, giving Wang his freedom and giving the Chinese people a republic. Wang was then offered the governorship of Guangdong province, but chose to turn it down, going instead to France to study.

Wang returned to China and in 1917 became Sun Yat-sen’s personal assistant, a position he held until Sun’s death in 1925. Becoming the chairman of the national government, Wang found himself competing for power with none other than Chiang Kai-shek, who ultimately based a government in Nanjing. Wang, in the meantime, created an alliance with the communists in Wuhan. When that relationship inevitably broke down, it threw additional support to Chiang Kai-shek. Finally, however, Chiang and Wang reconciled in 1932. Chiang remained in charge of the military; Wang Jingwei took up the presidency of the Nationalist Party.

Thus, when Wang Jingwei took up his leadership position in 1940 as head of the Japanese-led government, it hardly needs to be said that he was immediately branded a traitor to China. In fact, his treachery was one of the few points the Nationalists and Communists could agree on.

China’s Nationalist government had been engaged in a civil war with Chinese Communist revolutionaries for years before the Japanese invaded China in 1937. At that point, the two adopted a united military front to face and fight the occupying Japanese forces, an alliance that brought the two Chinese sides no closer to either political or ideological agreement. Nonetheless, on the case of Wang Jingwei, the two sides agreed that he had betrayed China. Wang therefore had the dubious distinction of being named a traitor by both sides of the political spectrum in China, a frustrating and untenable position for a man who saw his cooperation and collaboration with the Japanese enemy as a “safeguard” for all of China — and as a mandate of the principles of Pan-Asianism as defined by Dr. Sun Yat-sen.

As George Lowe wrote in the Duke East Asia Nexus in 2013, Wang Jingwei “believed that a ‘War of Resistance’ would be disastrous to the nation.” Lowe also noted that Wang “pointed to Pan-Asianism in order to justify his collaboration.”

“In order to show that he was staying true to the nationalist principles which had won him such prestige (not to mention high office) in the 1930s, Wang often pointed to the concept of ‘Dr. Sun Yat-sen’s Pan Asianism’… In a radio address of June 1941, Wang criticized the nationalists for not staying true to Sun’s legacy and having ‘failed to make united efforts for the attainment of that ideal [Pan-Asianism].’”

Wang Jingwei used his interpretation of the vision and imperatives of Dr. Sun Yat-sen to justify his decisions. Allowing himself to be co-opted by the Japanese occupiers to head up the newly established collaborationist government in Nanjing, was, he argued, a way to protect the Chinese people, and to advance China’s interests in the long run. Those interests had been spelled out by Sun in his speech on Pan-Asianism, delivered in Kobe, Japan on November 28, 1924.

In that speech, Sun laid bare his views on the state of Asia, openly addressing issues of race, imperialism, oppression, and colonialism. Sun began his speech by saying that “Asia, in my opinion, is the cradle of the world’s oldest civilization. Several thousand years ago, its peoples had already attained an advanced civilization… It is only during the last few centuries that the countries and races of Asia have gradually degenerated and become weak, while the European countries have gradually developed their resources and become powerful.”

Once European nations grew strong, Sun said, they “penetrated into East Asia, where they either destroyed or pressed hard upon each and every one of the Asiatic nations, so that thirty years ago there existed, so to speak, no independent country in the whole of Asia. With this, we may say, the low water mark had been reached.”

Sun outlined his vision of Pan-Asianism as stemming from “a problem of comparison and conflict between the Oriental and Occidental culture and civilization.” In Sun’s mind, “Oriental civilization is the rule of Right; Occidental civilization is the rule of Might. The rule of Right respects benevolence and virtue, while the rule of Might only respects force and utilitarianism. The rule of Right always influences people with justice and reason, while the rule of Might always oppresses people with brute force and military measures.”

These sentiments influenced Wang Jingwei to choose collaboration with Japan in the name of Pan-Asianism. The precepts and principles of Sun Yat-sen loomed large then in the mind of the man who, perhaps perversely, felt that collaboration was a better way to protect the Chinese people than outright defense against a vastly superior force.

And some of these same assumptions are reflected in speeches from the pinnacle of leadership today in China. Xi was clearly drawing from the same well as Sun when, in 2014, he told an audience in Berlin that “The pursuit of peace, amity and harmony is an integral part of the Chinese character which runs deep in the blood of the Chinese people.” While Xi didn’t explicitly criticize the “occidental civilization” of his hosts, he did make an implicit dig at Europe and the United States: “China was long one of the most powerful countries in the world. Yet it never engaged in colonialism or aggression.”

It’s unsurprising that, later in the same speech, Xi quotes Sun directly: “Dr. Sun Yat-sen, the pioneer of China’s democratic revolution, had this to say, ‘The trend of the world is surging forward. Those who follow the trend will prosper, and those who go against it will perish.’ … What is the trend of today’s world? The answer is unequivocal. It is the trend of peace, development, cooperation and win-win progress.” Here, Sun has been repackaged to advance Xi’s favorite foreign policy mantras, which collectively imply advancing China’s global leadership.

Sun Yat-sen was prominent in the mind of Wang Jingwei then, as he has been in the minds of every Chinese Communist Party leader since 1949, including Xi Jinping today. Wang would probably have agreed with Xi’s declaration in 2021 that Sun “was a great national hero, a great patriot, and a great pioneer of China’s democratic revolution.”

While the words and spirit of Sun inspired Wang to collaborate with China’s enemy in 1940, today it is Sun’s nationalist fire that has taken centerstage. But both impulses do share a common thread: Sun’s conception of the ongoing clash between “Orient” and “Occident,” between “Asian values” and the West’s “rules-based international order.”