Despite being soundly defeated at Sunday’s election, Thailand’s military has a gift-that-will-keep-on-giving that allows them to render a pro-democracy coalition unworkable. That gift is the unelected Senate, quietly formed under the military-drafted 2017 Constitution, which can veto appointments, prime ministerial appointments, and legislation.

The May 14 election was preceded by unprecedented debate about the role of the military and the monarchy and resulted in a strong victory for pro-democracy parties, most notably, the Move Forward Party which won an estimated 151 representatives in the 500 parliament. The anti-military Pheu Thai Party, which is closely associated with fugitive former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, won a projected 141 seats, allowing for an anti-conservative coalition with a comfortable majority.

The election is a resounding defeat for the military which ruled under a junta from 2014-2019, and through a tainted elected government since. Thais rejected Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha’s splashy, well-funded campaign as head of the United Thai Nation Party, which won just 36 seats. The pro-conservative Democrat Party is on track for just 25 seats – a humiliation for Thailand’s oldest political party.

But however the chips fall with the elected House of Representatives, the conservatives will dominate. The junta that ruled between 2014 and 2019 replaced the split appointed/elected senate under its captive Constitution of 2017. All 250 senators are appointed by the military and can in effect give the “thumbs up” or “thumbs down” to any act of the new government. They sit for five-year terms and unlike the exciting, young faces of the elected parliament, are obscure mid-tier elites — academics, former government commissioners, and conservative media figures — that few have heard of.

As the new government takes form (likely a coalition of the Move Forward Party and Pheu Thai), the Senate’s importance as Thailand’s holdout of conservative, pro-military power may come to the fore if the elites choose to obstruct and tie down the new government.

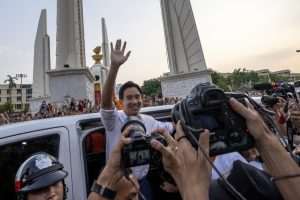

In the immediate term, the elected coalition’s choice for prime minister will be subject to Senatorial approval, requiring negotiations and concessions to the Senators. The most likely candidate from the Move Forward side is its 42-year-old leader Pita Limjaroenrat, although the Senate and allied parliamentarians may use a thin legal case to obstruct his appointment or force him to step down after he secures the nomination. The case relates to Pita allegedly owning shares in the defunct television station ITV, for which he is being investigated by the National Anti-Corruption Commission, whose members are well known for conservative leanings and for alignment with the conservative PDRC movement that helped unseat the Pheu Thai government of Yingluck Shinawatra in 2014.

Whether the Senate decides to block the coalition’s prime ministerial candidate outright or allow the government to form only to obstruct it at every turn, remains to be seen. The role of Thaksin in the backroom negotiations that will occur over the following weeks, and his influence over the Move Forward Party is also unclear.

If the elites decide to take the obstructionist path, the Senate can serve as the military’s “men on the ground” at every turn, holding reform and democracy down in lieu of a military coup. Policies deemed “populist” can be delayed or vetoed or bogged down with endless amendments and scrutiny at the committee level. Cabinet appointments can be scrutinized ad nauseam or blocked outright. The Senate would aim to wear down the government and discredit the institution of elected representation in Thailand.

If law-making is obstructed and delayed by the Senate and the government grinds to a near standstill, the conservatives may declare the elected government dysfunctional and call for a return to the more efficient days of military rule. Another possibility is that the elite force through a conservative coalition through a “judicial coup” similar to 2011, when the Democrat Party was elevated to control of the government through a complex undermining of the elected government of pro-Thaksin allies. For the elites, none of these options is appealing for the simple reason they have all been tried and have all failed. Coups, judicial meddling, and free and fair elections have all led to the same result: victories for ant-conservative forces.

If the conservatives pick the obstructionist path, it will likely increase Thais’ anger and frustration with the traditional pillars of the military, the monarchy, and the business elite. Thailand’s pro-democracy forces may be left with little option except for a return to the streets under 2010-style protests.

Rather than being a turning point in favor of democracy, the 2023 election may spell the beginning of a long struggle between the conservative elite and pro-democracy forces.