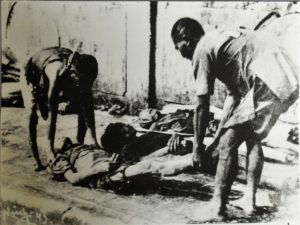

More and more starving folks were flocking to different places. In the market, many people were selling children. In my village, some kidnapped children to sell in markets on the other side of the Red River. There were even people who specialized in trafficking children, as if they were buying and selling chickens and pigs. But now there was nothing to eat, so who would still buy children? They were being caught and then brought back. It was miserable. At that time, Hanoi was not yet hit by famine, but many hungry people came here, making streets and alleys of Hanoi full of misery and hardship: The more chaotic it got, the more panicked people became when they saw hordes of hungry people pouring in… People sat, and the dead lay scattered on the sidewalks. Day and night, carts pulled dead bodies aimlessly going by.

It is almost unbelievable that the horrific scenes of the 1945 famine, as depicted in this translated excerpt from “Old Story of Hanoi” by renowned writer Tô Hoài (1920-2014), occurred just a few decades ago in Vietnam’s bustling capital city.

The Great Famine of 1945, also known as Nạn đói Ất Dậu in Vietnamese, took place in Tonkin and Annam under French and Japanese occupation. According to government statistics, the famine caused 2 million deaths in northern Vietnam, while international documents estimate the death toll at around 1 million, or approximately 8 percent of the population. The tragedy formed a key part of modern Vietnam’s history. Cultivating more land and addressing food shortages were key elements of Viet Minh propaganda, and preventing another famine was central to the communist regime’s legitimacy.

Vietnamese state leaders have long touted the country’s rice export successes as a sign of wise leadership, highlighting Vietnam’s status as the world’s second-largest rice exporter and one of the fastest-growing economies. However, the Great Famine is largely overlooked. Each year, Independence Day is celebrated on September 2, but with only fleeting reference to the famine that preceded the 1945 declaration of independence.

While the government has not actively suppressed discussion of the famine, calls for official commemoration of the 1944-1945 famine have yet to receive a response. Such calls from Vietnamese historians have been covered by non-state media outlets and featured in BBC reports, but Vietnamese domestic media have not given them attention.

Top-down Nonchalance

In September 1940, the Japanese military entered what is now known as northern and central Vietnam, following an agreement with French colonial administrators. They remained there until the end of World War II, resulting in the Vietnamese people being under dual colonization.

Although multiple factors contributed to the 1945 famine, the Japanese occupation played a significant role. The Japanese directed the destruction of rice fields in favor of cultivating jute, and stockpiled rice for domestic consumption and export. Historians widely agree that the Japanese military’s efforts, coupled with their economic policies for the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, particularly rice requisition, were key factors in the Vietnamese starvation.

This chain of events was reflected in Ho Chi Minh’s Declaration of Independence, issued just a few months after the famine:

In the autumn of 1940, when the Japanese fascists violated Indochina’s territory to establish new bases in their fight against the Allies, the French imperialists went down on their knees and handed over our country to them. Thus, from that date, our people were subjected to the double yoke of the French and the Japanese. Their sufferings and miseries increased. The result was that, from the end of last year to the beginning of this year, from Quang Tri Province to the North of Viet-Nam, more than two million of our fellow citizens died from starvation.

According to a Hanoi-based historian, there have been small-scale grassroots initiatives to commemorate victims of the famine in different parts of northern Vietnam, For example, the memorial Hợp Thiện was completed in 1951 via charity funds raised by residents of Hanoi. Nonetheless, the government does not seem to be interested in a national project, even though since the mid-1990s, there has been a significant increase in both the quantity and diversity of memory-related initiatives in Vietnam.

“Official memory projects need to be approved by the government,” said the historian.

Professor Văn Tạo, former head of Vietnamese History Institute, and Professor Furuta Motoo from the University of Tokyo started working on a project in the 1990s to break the silence on the underwritten tragedy. Their joint work, which collected oral histories from hundreds of famine survivors, met with disapproval from the government, according to Professor Ho Tai Hue Tam from Harvard University.

“Those who experienced it [the famine] are mostly dead,” the professor remarked via email. “Currently, both governments and people are more interested in the post-war, post-Doi Moi prosperity, which, in the post-COVID period, seems to be slipping away.”

The growing Japan-Vietnam relationship, which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year, contributes to the famine’s obscurity. Japan is now the country’s largest source of official development assistance and the third largest foreign investor. The Vietnam-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement was signed in December 2008 and enacted in October 2009, and in 2011, Japan became the first G-7 country to formally recognize Vietnam’s market economy status. In 2014, Japan became the first G-7 country to strike a strategic comprehensive partnership with Vietnam. In 2023, a book by former Japanese Ambassador to Vietnam Umeda Kunio was published in Vietnamese, entitled “Japan and Vietnam are natural allies.”

According to Professor Ken MacLean from Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, who studies human rights violations and how such experiences are recorded, the Vietnamese government is not inclined to bring up a potentially contentious diplomatic issue.

“By the 2000s, the government was far more interested in Japanese investment,” MacLean wrote in an email. “The issue of Japanese obligations never became a pressing public demand in Vietnam with regard to the criminal tragedy that occurred.”

Unlike the West, Japan generally sidesteps criticism of human rights issues in Vietnam. The Japanese government is reluctant to respond to the appeals of advocacy groups, which urge Japan to exert pressure on Vietnam regarding its human rights situation. This reluctance stems from Japan’s apprehension that any criticism of Vietnam’s human rights record may result in Vietnam aligning more closely with China.

The Famine That Helped Viet Minh

Historian Ngô Vĩnh Long, in his book “Before Revolution: The Vietnamese Peasants under the French,” asserted that prior to the French arrival, the land system in Vietnam was fairly responsive to the people’s needs. During the colonial era, however, land was mostly accorded to French citizens, Vietnamese elites, and Chinese merchants. Lower death rates were recorded among those who had access to some private land; those without farmland were more likely to die.

Hunger was common under French colonial rule, albeit not to the extent of the 1945 famine. Even though the capital city did not experience starvation, food shortages were not uncommon. In that sense, the famine seen across 32 provinces from 1944-1945 did not start but merely intensified under the Japanese occupation.

As explained by historian Nguyễn Thế Anh, the Viet Minh front, which was established in 1941, used the famine to mobilize illiterate and impoverished peasants. The question of survival made the masses follow the independence coalition. In addition, the famine contributed to the political chaos that made possible for the August 1945 revolution to happen and for the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) to lay claim to it.

In numerous domestic outlets, the government has discredited arguments made by historians that the communist government’s ascent to power in 1945 was a fluke. In that sense, allowing public debates on or widespread commemoration of the famine could potentially lead to revisiting other historical events.

There were two independent governments that both contributed to putting an end to French colonization: the American-backed Viet Minh and the Japanese-backed Empire of Vietnam, established in Hue in April 1945 and led by Trần Trọng Kim, a well-respected scholar. Any attempt to commend Tran is seen as distortion of historical facts, a punishable crime in Vietnam.

The CPV does not acknowledge non-communist nationalist movements as legitimate groups capable of assuming power, asserting that they were the only valid group to do so.

The four-month-long government under Trần, made up of technicians rather than politicians, poses a significant threat to the legitimacy of power of the CPV today – and its legacy is intricately tied to the 1945 famine. As historian Nguyễn Thế Anh commented, the Trần administration and the Vietnamese in general took a more active role in managing the crisis than the French and the Japanese. By June 1945, the famine was nearly over.

Trần’s famine-relief programs not only helped to reduce the people’s misery but also provided the masses, especially the youth, with an opportunity to engage in social activities. His short-lived government also contributed to national independence, the elevation of Vietnamese language status, and Vietnamization of the French colonial administration, changing the national name to Viet-Nam, and securing territorial unification prior to Japan’s surrender.

Yet Trần’s elite background only allowed him to initiate a top-down revolution that had little contact with the peasant class, who made up the majority of the population. In fact, in party-enabled historiography, Tran can only be referred to as a scholar or educator, or at most a leader of a pro-Japanese puppet government. As a result, the memory of his underrated government has fallen into oblivion.

Japan’s Reparations Tangled in Vietnam’s Civil War

In the years since, Japan has made war reparations to Vietnam, but not to the CPV. According to the book “Japanese Relations with Vietnam, 1951-1987” by Masaya Shiraishi, Japan omitted communist nations from the list of beneficiaries of war reparations, even though it did not sever all contact with the North Vietnamese government.

The Japanese government only established official relations with the southern government, while ignoring the suffering of northerners under Japanese occupation. The CPV has always denied that the short-lived Republic of Vietnam (RVN) was an internationally recognized government. Back then, only a few countries recognized the communist government in Northern Vietnam, a fact that the government does not want its youth to know, though it carefully lists all the countries that protested against the Vietnam War.

The RVN aimed to gain recognition as the sole rightful recipient of war reparations from Japan. In 1955 Ngô Đình Diệm brought up compensation with Japan as its diplomatic partner. Disagreement over the amount was a stumbling block to trade relations between Japan and the RVN. In 1959, the RVN became the sole recipient of Japan war reparations in Vietnam.

Japan paid compensation in the form of development aid – it was the third biggest contributor to the South Vietnamese economy under Diệm – though the amount remained questionable. The 1959 reparations agreement pledged a total of $55 million, most of which was utilized to finance the Da Nhim hydroelectric project. However, relations between the two nations became strained as left-wing support for the communist regime in Hanoi increased in Japan.

Only Grim Suffering, No Glorious Sacrifice

Historian Benoit de Tréglodé, in his book “Heroes and Revolution in Vietnam,” found that the CPV only prioritized the commemoration of those fighting against colonizers and imperialists after 1925, creating “a patriotic elite.” The CPV has the final say of who can be considered liệt sĩ, martyrs who died a glorious death in defense of the country.

The millions who died in the Great Famine did not fit the CPV’s grand narrative of national salvation. In the hierarchy of heroic deaths analyzed by Treglode – including dying in combat, dying while engaged in a war-time activity, or being declared missing in action – those who perished from famine were not included or recognized, despite the loss of their lives and dignity.

Even getting a sense of the devastation is difficult. The number of female victims was less documented or emphasized, as male demographics were deemed more significant by colonizers. This was due to colonial policies that mandated only men to pay the “head tax” or “body tax,” which led to their numbers being tracked more carefully. In addition, no one counted the number of people who did not die but were permanently weakened as a result of malnutrition.

It is an open secret that the CPV-led government meddles with historical statistics, including those related to the famine. The CPV has historically relied on statistics as a crucial element in its attempts to monopolize all forms of representation under its authority. The CPV, Ministry of Defense, and Ministry of Foreign Affairs maintain their own private archival systems, limiting access to closely monitored officials. Regrettably, Vietnamese academics, scholars, and students are denied entry to these closed archives.

Merely tallying the death toll fails to acknowledge the numerous victims who were impacted, either directly or indirectly, by the diminished and downplayed Great Famine. Even today, descendants of those affected may continue to silently bear the consequences.

Cannibalism and the sale of children were among the numerous crimes that resulted from the Great Famine. These stories should be told. History encompasses not only the overarching narrative, but also the individual stories of everyday people, especially vulnerable populations that are still remembered. Microhistories deserve a better position.

As the Vietnamese have a tradition of honoring their ancestors, commemorating the victims of the Great Famine serves not only to honor the deceased but also to respect the living. These victims did not die in peace. Nor can their descendants live in peace.