The dramatic but short-lived armed rebellion of the Russian private military company Wagner Group and its leader, Yevgeny Prigozhin, may have ended with a whimper, not with a bang, but for a brief moment it shook Russia’s system of governance to the core. As one of Russia’s closest strategic partners, China monitored the abortive revolt very closely. Given the opacity of China’s political system, there is no way of knowing exactly what lessons its leaders have gleaned from these events, but we can nonetheless make some educated guesses about what conclusions they might have drawn.

China’s Immediate Reaction

As the dramatic events were unfolding in Russia on June 23-24, China’s state-controlled media were reluctant to report on them. State media covered the news from Russia very sparingly, indexing the relevant reports very low. To the extent that they did cover the revolt, they essentially offered only the official version of events as propagated by the Russian authorities.

During this time, there was no high-profile reaction from the Chinese government. Finally, on June 25, following an unscheduled meeting with Russia’s Deputy Foreign Minister Andrey Rudenko, China’s Foreign Minister Qin Gang publicly expressed Beijing’s firm support for and confidence in President Vladimir Putin, declaring that the events were part of Russia’s “internal affairs” and that “China supports Russia in maintaining national stability.”

As the Kremlin was picking up the pieces from the abortive rebellion, Russia’s state media began to develop a narrative of “business-as-usual,” framing the foregoing events as a minor disturbance that was quickly contained by a resolute president, while the Russian public had rallied behind him. China’s government-controlled media eagerly copied and amplified this narrative and projected an image of stability and minimal impact on Russia, reporting that the Wagner “incident” had been swiftly controlled due to Putin’s wisdom and his overwhelming support from Russian society. Chinese outlets even suggested that it would ultimately strengthen, rather than weaken, Putin’s rule in Russia.

Even so, it was undoubtedly not lost on China’s leaders that the actual sequence of events on June 23-24 had been dramatically different. Prigozhin’s militia had been able to take de facto control of a city of more than a million people (while being cheered by many local residents), occupying several key military installations and shooting down multiple Russian aircraft. Amid images of panicked authorities using excavators to destroy a highway leading to Moscow (only to hurriedly repair it again hours later) and reports of senior officials fleeing the capital, Putin himself had exclaimed that the “the fate of our people is being decided” by the events. Ultimately, Russia’s security services were unable – or unwilling – to effectively confront the Wagner troops until they reached the borders of the Moscow region and Prigozhin himself chose to abort his march on the capital.

China’s Interpretation of the Events

Why did it take China’s government so long to respond to the revolt in Russia? In all likelihood, China’s leaders were as surprised and confused by the unexpected turn of events as all other outside observers (save for the U.S. government and some of its closest allies, who had reportedly been forewarned by U.S. intelligence). Indeed, there is much to suggest that for Beijing, these events were particularly difficult to compute.

The Chinese leadership has long counted domestic threats to regime stability among its topmost policy priorities, and it has been preparing extensively for such an eventuality, whether at home or on the territory of its fellow authoritarian partner states. In this event, however, the challenge to the Kremlin’s authority came from a place that was probably quite unexpected for Beijing: not from the pro-Western liberal opposition (in the form of anti-authoritarian mass protests and an attempted “color revolution”), but from within parts of Putin’s own military apparatus and the ultranationalist forces he himself had cultivated. It is doubtful that Beijing was adequately prepared for such a scenario.

China’s leaders (much like Russia’s) are generally inclined to see the hidden hand of the United States and its Western allies as the driving force behind all threatening and destabilizing political events. Indeed, this is the narrative that Chinese state media tend to propagate on a daily basis. Not long after the Wagner revolt had fizzled out, Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov began to insinuate that Western intelligence agencies might have played a role in triggering Prigozhin’s mutiny, and the commander of Russia’s National Guard (Rosgvardiya), Viktor Zolotov, claimed that “everything was inspired by the West. Everything was organized there. I don’t rule out the possibility that agents of the Western intelligence services were involved.” Unsurprisingly, leading Chinese media eagerly quoted and reproduced such speculations of Western involvement as well.

However, public propaganda aside, it must have been evident for China’s leadership that any Western involvement in the revolt was highly unlikely. On the contrary, Prigozhin and his militia were quite obviously a product of Putin’s own system and an integral component of his long-standing strategy to wage an unattributable “hybrid war” against the West. Prigozhin himself owed his rise to the president’s personal patronage. On June 27, Putin publicly stated that the Wagner Group had been entirely financed by the Russian state – notwithstanding countless assertions he had made in the past (for instance as recently as February 2022) that Russia’s government has “no involvement at all” in Wagner, as well as the fact that the private military company was technically illegal under Russian law.

The fact that such an unexpected challenge to Putin’s regime could have arisen from within his own inner circle probably means that Beijing will study the lessons from the revolt very carefully. That being said, the events are unlikely to have immediate repercussions for China’s strategic approach or the disposition of its own security organs.

Beijing has long dabbled with some limited forms of “hybrid warfare” of its own, particularly in its campaign for maritime expansion in the South China Sea. But unlike Putin, whose KGB pedigree goes some way to explaining his affinity for subversive, irregular, and unofficial “hybrid” outfits and tactics, Beijing has been averse to any form of private or semi-private military activity. There is no analogue to the Wagner Group in China. On the contrary, throughout recent years, China’s leaders have aimed to bring all military and security institutions in the country under the direct and permanent control of President Xi Jinping and the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Most probably, for China’s leaders the broader concerns about the Wagner mutiny and its potential repercussions for the Kremlin do not only stem from their fears that their close ally Putin might lose power. The prospect of domestic unrest unseating a powerful authoritarian regime has also long been one of the greatest perceived risks for China’s political elites themselves. Notwithstanding China’s outward strength and stability, concerns about domestic regime security and legitimacy have arguably been greater in Beijing than many outside observers perceive them to be. There can be little doubt that the revolt in Russia was a nightmare scenario for the CCP leadership, even though it was ultimately resolved relatively quickly.

Regime Security Cooperation With Russia

On issues of authoritarian regime security, there is no country that Beijing has cooperated more closely with than Russia. For years, Russia’s security services have been training intensely to suppress domestic insurrections, and Beijing has long tapped into Moscow’s expertise on how to counter domestic threats to regime security. The prevention and suppression of pro-democratic “color revolutions” has been one of the most frequent topics of discussion at Sino-Russian high-level meetings, and the security forces of both countries have engaged in long-running training and cooperation programs focused on quelling domestic rebellions.

Besides conducting large-scale bilateral military exercises since 2005, China and Russia have also held specialized joint exercises of their (paramilitary) domestic security forces throughout the last decade. In June 2013, special forces units of China’s People’s Armed Police (PAP) and the Internal Troops of Russia’s ministry of internal affairs conducted their first separate military drills, labeled “Cooperation 2013.” Since July 2016, on the Russian side, these separate military exercises with China’s PAP have been conducted by the newly formed Russian National Guard (Rosgvardiya), an independent domestic military force that was created out of the Interior Ministry’s Internal Troops and is under the personal command of the Russian president (it is therefore informally referred to as “Putin’s private army”). According to Roger McDermott, “the National Guard’s roots lie in Moscow’s wider efforts against color revolution as one of the most formidable challenges facing the Russian state.”

While China’s PAP (which, since 2018, has been under the exclusive control of the CCP) and Rosgvardiya have a variety of responsibilities, they are both focused on fighting internal threats, and a core aspect of their work has been suppressing political dissidents and quelling potential uprisings. Further PAP-Rosgvardiya joint exercises followed in 2017 and 2019 (prior to being interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic). Rosgvardiya Director Viktor Zolotov (a long-time Putin confidant) claimed in 2019 that “over the past three-and-a-half years since the formation of Rosgvardiya, we have already held 15 joint events” with China’s PAP. During the Wagner revolt, Rosgvardiya provided the troops that were deployed to defend the approaches to Moscow against Prigozhin’s renegade forces.

Besides the regular joint exercises of their internal troops, Beijing and Moscow have more broadly stepped up collaboration and exchanges between their internal security and domestic intelligence services in recent years. This included the creation of a bilateral Mechanism for Cooperation in the Field of Law Enforcement and Security in June 2014, which has been meeting annually and is headed by the secretary of the CCP’s Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission and the secretary of the Russian Security Council, two of the highest-ranking security officials in both countries. It is predominantly devoted to addressing domestic security challenges, including “the protection of state security [and] resistance to foreign interference in internal affairs.”

Beijing and Moscow have also extensively borrowed from each other’s strategies and technologies for public surveillance and have engaged in wide-ranging technological cooperation aimed at suppressing domestic anti-government activism and agitation (for instance with regard to surveillance technology and cybersecurity).

In light of this long-standing and intense cooperation with the Kremlin in the sphere of countering and suppressing domestic revolts and unrest, it was probably particularly unsettling for Beijing (and for Xi personally) that Russia’s internal defense mechanisms all evidently failed during the Wagner revolt. Prigozhin ended up marching on Moscow essentially unopposed while Rosgvardiya units scrambled to defend the capital against the approaching heavily-armed and battle-hardened Wagner forces. Again, China’s leadership will undoubtedly try to learn lessons from that.

China’s Future Relations With Russia

Even if Beijing’s doubts regarding the stability of Putin’s regime may have grown in the wake of the Wagner revolt, it is unlikely that these events will lead to immediate changes in China’s approach toward Russia. Since the onset of Putin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, China’s policy toward Russia has been characterized by consistent diplomatic and rhetorical support, intensified bilateral trade, frequent joint military exercises, and tacit consent for Moscow’s strategic aims in Ukraine (including an amplification of Russia’s narratives about the war in China’s state media).

For Xi, the dramatic events in Russia have likely served to highlight how wartime chaos can weaken powerful leaders, underscoring that the war in Ukraine is exerting a severe cost on his “best and bosom friend” Putin. In the best of cases, this might prompt Beijing to engage in more serious attempts to broker peace in Ukraine, compared with the half-hearted and half-baked attempts it has undertaken thus far. But the chances for this happening remain very modest. More likely, Beijing will sustain its current course of providing subtle support for Russia, while publicly proclaiming neutrality in the Ukraine conflict.

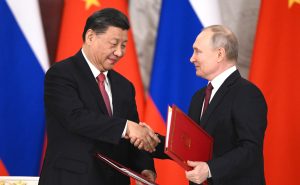

Overall, China’s leadership appears to be very invested in keeping Putin in power and trying to ensure that his position in Russia does not become too tenuous, because more than any other foreign leader he shares Xi’s main policy priorities: opposing Washington’s geopolitical and strategic goals, while also actively cooperating in bolstering regime security at home and opposing any form of foreign interference that might subvert it. If there was to be a more serious destabilization of governmental power in Russia in the future, Beijing would probably do everything it can – economically, politically, diplomatically – to prop up Putin, short of a direct intervention in Russia.

According to assessments by U.S. officials who directly liaised with their Chinese counterparts in the aftermath of the invasion of Ukraine, China’s commitment to assist Putin in dealing with the fallout from the war has been driven from the top, by Xi, over the objections of less senior officials in the Chinese government apparatus who seemed to be skeptical regarding the merits of a continued close partnership with Russia. In light of Xi’s frequent displays of camaraderie with Putin and the conspicuous convergence of their leadership styles in recent years (especially after Xi emerged victorious from a lengthy intra-CCP power struggle), it is likely that Xi fears that any weakening of Putin’s power and prestige within Russia could reflect negatively on his own leadership as well.

But Beijing’s commitments to Putin notwithstanding, the coming months might well see more active discussions in the Chinese leadership about what future relations with Russia after Putin might look like. It is very likely that the Chinese leadership’s confidence in the Russian president was further diminished by the events surrounding the Wagner revolt.

By all appearances, this confidence has already been eroding since Putin launched his ill-advised invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. China’s leaders seemed to be dismayed by Putin’s strategic choices, and senior U.S. intelligence officials stated in March 2022 that Beijing was unsettled and surprised by Russia’s military failures in Ukraine. This pre-existing skepticism has probably been reinforced by the Wagner revolt, amid a sense that Putin may no longer be fully in control of events in Russia, despite the fact that Russia’s elites ultimately stuck with him.

This is not helped by the fact that the prospects for a Russian military success in Ukraine look even bleaker now, following the fragmentation of the Wagner militia (which was previously one of the most effective fighting units among Russia’s armed forces) and an apparent purge of popular senior officers in the Russian military, including former supreme commander of the Russian forces in Ukraine Sergey Surovikin. Recent events will likely contribute to further diminishing morale among the Russian troops and pro-war Russian nationalists.

As regards Putin himself, the Wagner revolt, which was led by his own long-time protégé, will probably cause Russia’s president to place less faith in his domestic network of (once-)loyal associates and to seek even more assurances from those external partners that he considers particularly reliable (especially Xi Jinping). Stable ties with China and rhetorical support from Beijing will be important for Putin in projecting an image of domestic stability and “business as usual” in the coming months, as well as a sense that he remains firmly in control of the political situation.

As a consequence of the Ukraine war, a relatively isolated Moscow has already become unprecedentedly dependent on China, especially in economic and technological terms, a process that is increasingly turning Russia into something resembling a Chinese client state. In the aftermath of the abortive Wagner revolt, Russia will likely become even more structurally dependent on China than it already was.