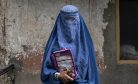

Despite promises made to the international community and the people of Afghanistan, the Taliban’s fanatical attitude toward human rights and women remains unchanged. In the two years since their military takeover of the country on August 15, 2021, the Taliban have effectively waged a war against women’s rights in Afghanistan and by extension against the globally recognized rights of women.

At the domestic level, the Taliban have almost entirely erased women from public life and have violently suppressed their protests. At the global level, the latest edicts banning beauty salons, barring women from working in the U.N. and with international NGOs, and a recent directive to stop any international NGOs from offering education to out-of-school children effectively set a record for repression. The U.N. Secretary General’s Special Representative for Afghanistan Rosa Otunbayeva acknowledged the fact that “in the history of the United Nations, no other regime has ever tried to ban women from working for the Organization just because they are women. This decision represents an assault against women, the fundamental principles of the U.N., and on international law.”

Afghanistan’s weary civil society and the overstretched global human rights system continue to improvise and resist. The struggle for the protection of fundamental rights and the Taliban’s violent pushback have molded Afghan women’s groups into a strong, resilient, and historically unique female solidarity movement. On the international level, despite competing demands, the efforts for the protection of human rights, prevention of further atrocities, and establishment of an accountability mechanism for Afghanistan continue.

These actions, however, fall way short of addressing the challenges and expectations.

Afghanistan’s Women’s Movement

Afghan women attained the right to education and suffrage in the early 20th century. While conservative and patriarchal forces, years of conflict, and civil war including the Taliban’s first stint in power 1996-2001 continued to impede the progress of women’s rights to education, employment, and political participation, the majority of incumbent governments remained committed to the protection of their basic rights. Women and girls in major cities had the opportunity to get an education and work in almost all sectors.

In the last two decades under fairly progressive states and with significant international investment, women achieved greater access to education, employment, and participation in social, political, and economic affairs of the state and society. Over 3 million girls were going to school and universities. Women were serving as ministers, judges, legislators, senior civil servants, and governors. Despite intense conflict over the last decade women remained resilient and committed to pushing for their rights and greater equality in society.

The return of the Taliban to power threatens to wipe out a century’s worth of hard-gained rights. But Afghan women have not simply given up. Instead, after two days — on August 17, 2021 — even as high-ranking officials were fleeing and NATO troops were busy with evacuations, brave Afghan women confronted the Taliban in the streets of Kabul and other cities, demanding their rights. They faced cruel repression, arbitrary detention, imprisonment, torture, and forced disappearances. With a brutal crackdown, the Taliban attempted to make them silent, but their voices were supported and echoed by their sisters in exile and diaspora communities.

During nearly two years of concerted and brave advocacy and action, Afghanistan’s women’s movement inside and in exile has demonstrated maturity, resilience, and fortitude. They understand the nuances of the sociopolitical crisis in country and the shift in international politics away from Afghanistan. They not only have skills and expertise but also maturity and resilience. The core of the current women’s movement that is resisting both in and outside of Afghanistan is not made of privileged women but active ones. Even during the last two decades of democratic rule, sociopolitically active women paid a very heavy price. They endured family pressures, social harassment, predatory teachers, misogynistic bosses, and a megalomanic president who perhaps used their premature appointment to cynically fulfill donor requirements.

Afghanistan’s women activists and human rights rights defenders were often accused by the Taliban of having connections with the West and promoting Western values; however, their struggle remains a manifestation of the desire to protect their basic rights and dignity as equal human beings.

The Feeling of Betrayal

The disastrous U.S.-Taliban Doha Agreement of February 2020 and consequently the return of the Taliban’s “Islamic Emirate,” besides other ills, have turned Afghanistan — in the words of Shahrzad Akbar, former chairperson of Afghanistan’s Independent Human Rights Commission — into “a mass graveyard of Afghan women and girls’ ambitions, dreams and potential.” Today, Afghanistan is ground zero for human rights and a call of conscience for the international community, particularly the global feminist movement.

The favorite slogan of Zalmay Khalilzad, the Trump administration’s peace envoy, was that “nothing is agreed until everything is agreed.” When the U.S.-Taliban agreement was announced, then, the assumption among civil society and democratic forces in Afghanistan was that the deal would address, if not everything, at least the most important things. The deal was signed in a grand ceremony and in the presence of several female foreign ministers, some of whom were presiding over their country’s feminist foreign policies. However, as it turned out, respect for human rights and protection of women and the democratic forces of Afghanistan weren’t part of the definition of “everything.”

It was perhaps a little naïve to have expected Khalilzad, then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, or then-President Donald Trump to worry about the fate of women and democratic forces in Afghanistan. The most disappointing point for the women of Afghanistan is not why and how the Doha deal happened, but when and under whose watch the abandonment of Afghan allies, women, and girls, and the Taliban’s march to Kabul unfolded.

Sadly, the disaster unfolded under a Democratic administration in Washington, under the United States’ historic first female vice president, during the most progressive Congress with a powerful female speaker, and last but not least the first female administrator of USAID, herself a loud champion of women’s rights. Adding the European and other female foreign ministers whose countries engaged with the Taliban to the list, the expectation of a better inclusion and protection of Afghan women in high-level decision-making doesn’t seem a farfetched request.

Beyond Routine and Rhetoric

The situation of human rights and women’s rights in Afghanistan features in various U.N. and multilateral platforms; however, given the depth and breadth of the practical and normative challenge the Taliban rule imposes, the majority of these discussions are narrow and often cosmetic.

The prevailing assumption at the international level is that, like many other authoritarian regimes, the Taliban abuse certain groups to consolidate power or protect their national cultural peculiarities. Hence to some member states, it is part of the usual range of challenges. Another group thinks that since the Taliban base their restriction on women’s rights on their interpretation of Islam, it’s the duty of Muslim majority states and the Organization of Islamic Countries to find a solution.

The tough reality is that the issue is far more serious. As the world celebrates the 75th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) a landmark achievement in human history, a violent extremist group that seized a mid-size strategically located U.N. member state entirely discards the fundamental principles of the U.N. Charter, the UDHR, and almost all other major international treaties and conventions.

A series of incredibly shocking reports have been published in recent months, such as the UNAMA report on corporal punishment and the death penalty in Afghanistan and Amnesty International’s reports on illegal killings and mass punishment in Panjshir province and the Taliban’s war on women. These reports, given a lack of access to information and clampdown on free media, are just the tip of the iceberg. The Taliban are pushing a country on the brink further into a deep abyss.

On June 19, 2023, the United Nations Human Rights Council held its second Enhanced Interactive Dialogue on the Human Rights Situation of Women and Girls in Afghanistan since the Taliban’s military takeover. The U.N. Special Rapporteur on Afghanistan and the Chair of the Working Group on Discrimination against Women in Law and Practice presented a new joint report. The two visited Afghanistan from April 27 to May 4, 2023. The report illustrated instances of systemic discrimination, oppression, and an institutionalized framework of gender apartheid, unparalleled anywhere in the world.

The Taliban are openly challenging the very fundamentals of the international normative system and standards built over the past 75 years through the dedicated work of U.N. member states, including the state of Afghanistan, and civil society organizations around the word.

The Way Forward

The challenges are indeed unprecedented, but discussions and solutions need to move beyond routine and rhetorical.

Afghanistan’s women’s movement, being pushed into a narrow corner, has the opportunity to consolidate intellectually and practically, and rise to the occasion as a consistent and cohesive actor. Disagreements over methods of resistance, and imperatives of generational differences naturally lead to the creation of more than one organization. However, losing sight of the larger purpose — ending gender prosecution and the reclamation of the inalienable rights of millions of Afghan women and girls — due to ethnic and linguistic affiliation, or further division between those inside Afghanistan and those in exile, will seriously undermine the nascent movement. The international community and civil society organizations can play a significant role in bringing this diverse coalition together.

The mandate of the special rapporteur on Afghanistan is up for renewal during the upcoming September session of the Human Rights Council. This mandate should be further strengthened to include a gender responsive investigative mechanism, to monitor and regularly report on, and collect evidence of, human rights violations and abuses committed across the country.

Efforts to rally the support of Muslim-majority countries to address the dire situation of women’s rights in Afghanistan is critical, but it cannot and should not be used as a substitute for concerted international action.

Commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the UDHR under the slogan of “Dignity, Freedom, and Justice for All,” later this year offers a great opportunity to have a summit-level discussion on the unprecedented situation of human rights in Afghanistan, the challenges it poses, and actions to be taken.

To address the immediate challenge of education, for both girls and boys, without reliving the Taliban’s de facto authority of its responsibility, a global initiative for massive online education in Afghanistan is needed. An education committee in exile comprised of Afghan education experts could be established to co-lead the initiative, monitor the implementation of the standard curriculum, and serve as an accreditation authority for online schools.

These efforts cannot wait.