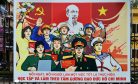

Democracy is waning in Southeast Asia, yet the United States is ever friendlier with its autocratic leaders. The sight earlier this month of U.S. President Joe Biden standing alongside Nguyen Phu Trong, the Vietnamese Communist Party chief, warmed the veins of all those keen to lambast Washington for rank hypocrisy and double standards.

Herein lies the problem for the United States in Southeast Asia. The region is very undemocratic; it was undemocratic during the era of “Chimerica” in the 2000s and it was undemocratic during the opening years of the Second Cold War in the 2010s. However, China is the “revisionist” power in the region, an adjective that 41 percent of Southeast Asians themselves used to describe Beijing in a 2022 survey. As a result, America must combat this by being the “status quo” power in the region. But to be the status quo power, Washington must defend the status quo in Southeast Asia, which is undemocratic.

Hun Sen, the Cambodian prime minister since 1985, resigned last month and handed power down to his eldest son, Hun Manet, who Western governments reckon could be something of a reformer – and, short of options, the United States is now taking a wait-and-see approach. One can only imagine that U.S.-Indonesian relations won’t change if Prabowo Subianto is elected president next year, despite him having been sanctioned by the U.S. in the past. Communist Laos will be fawned over next year when it’s chair of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). The crimes committed under Rodrigo Duterte’s presidency in the Philippines now result in an imbecilic glaze from Washington.

Because Biden has convened two Summits for Democracy and claimed there is actually an ideological edge to the Second Cold War, unlike his predecessor who was a lot more honest that the U.S.-China rivalry was primarily an economic one, all this has led to accusations of hypocrisy – indeed, accusations that America is reverting back to its First Cold War days when it permitted all manner of wickedness in the name of defending democracy: backing Indonesia’s occupation of Timor-Leste, propping up corrupt regimes in Saigon, illegally bombing Cambodia, supporting anti-communist tyrants in Thailand, South Korea, Taiwan, the Philippines, etc, etc.

However, there is an opinion, not an entirely unreasonable one, that says statecraft is a grubby business and the United States cannot avoid double standards. Washington, it says, doesn’t have the luxury of only being friendly with doppelganger states. There are increasingly few liberal democracies, after all. If it is serious about confronting a revisionist China and defending peace in Southeast Asia, it will have to do business with countries that it would ordinarily prefer not to have dealings. Moreover, hypocrisy and double standards are also unavoidable, the narrative goes, because a superpower has to take a genuine interest in perhaps four-fifths or more of all of the countries in the world and because it possesses a sprawling foreign policy bureaucracy covering different departments, each with their own selfish desires and each rather aloof from one another. In other words, it has to be discriminatory.

Of course, all this looks like rank hypocrisy of the intentional sort when one is sitting in the foreign ministries of Phnom Penh or Manila, for instance, where at best you have to take an interest in perhaps a dozen or two dozen countries, most of which are neighbors, and almost never is there the expectation that you must solve a problem in one of those states. Indeed, one imagines that most Cambodian foreign ministry officials can go an entire career without a passing thought of events in Africa, Latin America, South Asia, and the Middle East.

That’s all rather understandable but where does it get you? On the one hand, it leads to the quite eloquent and concise National Security Strategy, which states that Washington is willing to work with autocratic regimes that “do not embrace democratic institutions but nevertheless depend upon and support a rules-based international system.” In other words, authoritarian states that are on the side of the United States.

On the other hand, it also invites appeals to go further. Why not become even more hypocritical? Brahma Chellaney, an analyst quick onto anything that might be marketable as realpolitik, made an astute observation and before reaching a woeful conclusion in a recent piece for Nikkei Asia. As he noted, referring to Vietnam, Biden’s stopover “in one of Asia’s more authoritarian countries is the latest reminder of how Biden is not hewing to his own simplistic narrative of a ‘global battle between democracy and autocracy,’ implicitly recognizing that the approach would crimp the wider pursuit of U.S. diplomatic interests.”

One can only agree. But then Chellaney twists your arm with his follow up. If the U.S. can make friends with communist Vietnam, why not the military junta in Myanmar? America, he argues, could “potentially become a favored partner of Myanmar by gradually developing ties with its nationalist military – the only functioning national institution in the culturally and ethnically diverse country.”

How wrong this is about Myanmar’s internal situation is complemented by how wrong it is on international affairs. One might, for instance, point out that the junta is far from “functioning” (“lingering,” perhaps, is a better adjective) and one ought to change “nationalist” with “fascist” if you consider the Rohingya and its corporatist economics, while it’s equally true that the U.S. could be the favored partner of Myanmar if it offers genuine assistance to anti-junta forces and helps them to take power.

Yet the main problem is that it conjures a geopolitical reason for America to be more hypocritical where none exists. U.S. support for Myanmar’s junta would in no way be comparable to its support for Vietnam, not least because it’s far from conceivable that Myanmar needs defending from a militarily assertive Beijing or that the junta would welcome U.S. support. For this comparison to work, Biden would have arrived in Hanoi earlier this month and sided with the Communists against an actual anti-communist rebellion that’s banging on the doors to Hanoi. The reader must appreciate the difference between Biden not condemning human rights abuses in Vietnam and him (in Chellaney’s imagination) siding with a military junta against an actual, flesh-and-blood revolutionary movement that might just win power.

In any case, the problem with a small amount of hypocrisy is that it allows invitations to act even more hypocritically. And, indeed, not just from pundits. As mentioned earlier, the lesson of the First Cold War was that one act of hypocrisy and self-violation leads to ever-worsening acts. Washington has to be hypocritical and discriminatory with how it interacts with other countries, but that doesn’t mean it has to pretend that it’s not being hypocritical or, indeed, fully embrace the hypocrisy past the point of limited self-interest. It’s not far-fetched to assume that the United States can seek to maintain friendlier relations with Vietnam at the same time as sincerely condemning its human rights abuses and one-party system. One can be a friend of an alcoholic without having to buy him a bottle of whiskey every time you meet. Indeed, Biden need not have so completely shunned these topics the way he did, nor have groveled so much at the feet of the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV).

Kurt Campbell, Washington’s Indo-Pacific chief, has called Vietnam the “critical swing state” in the Indo-Pacific. That would be true if Hanoi wasn’t such a calcified pendulum. But worth remembering is that, if freed from Chinese aggression, Hanoi would keep the United States at arms distance, a market for exports and nothing else. Indeed, one rarely hears cries about the CPV’s hypocrisy. Its theoretical rags are still inked with claims that Washington seeks regime change, that bourgeois democracy remains a tyranny, and that (disguised amongst the jargon) Vietnam’s closest partner should really be communist China if only those pesky South China Sea disputes could be overcome.

In international relations, everyone’s a hypocrite. We all know that. But statecraft, especially when values are on the line, is about how to be as least hypocritical as possible and, more importantly, self-aware of one’s own two-facedness. The United States is friends with some authoritarians, but that doesn’t mean it has to be friends with all authoritarians or start to imagine that those authoritarians are actually democrats. In real terms, conduct your geopolitical intrigue with the CPV but don’t support Myanmar’s military junta.