Driven by China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), from 2015 onwards rail-borne containerized cargo flows between the European Union (EU) and China increased steadily. Volumes hit a peak between 2020 and early 2022, the start of the war in Ukraine.

During 2021, well over 600,000 TEUs (twenty-feet equivalent units) were moved between Chinese and European railports, with westbound cargo accounting for some two-thirds of the total. The trade represented a total value of some $40 billion. By comparison, containerized ocean freight between Asia and Europe via the Suez Canal route amounted to some 26.5 million TEUs in the same year, of which over 19 million TEUs were westbound.

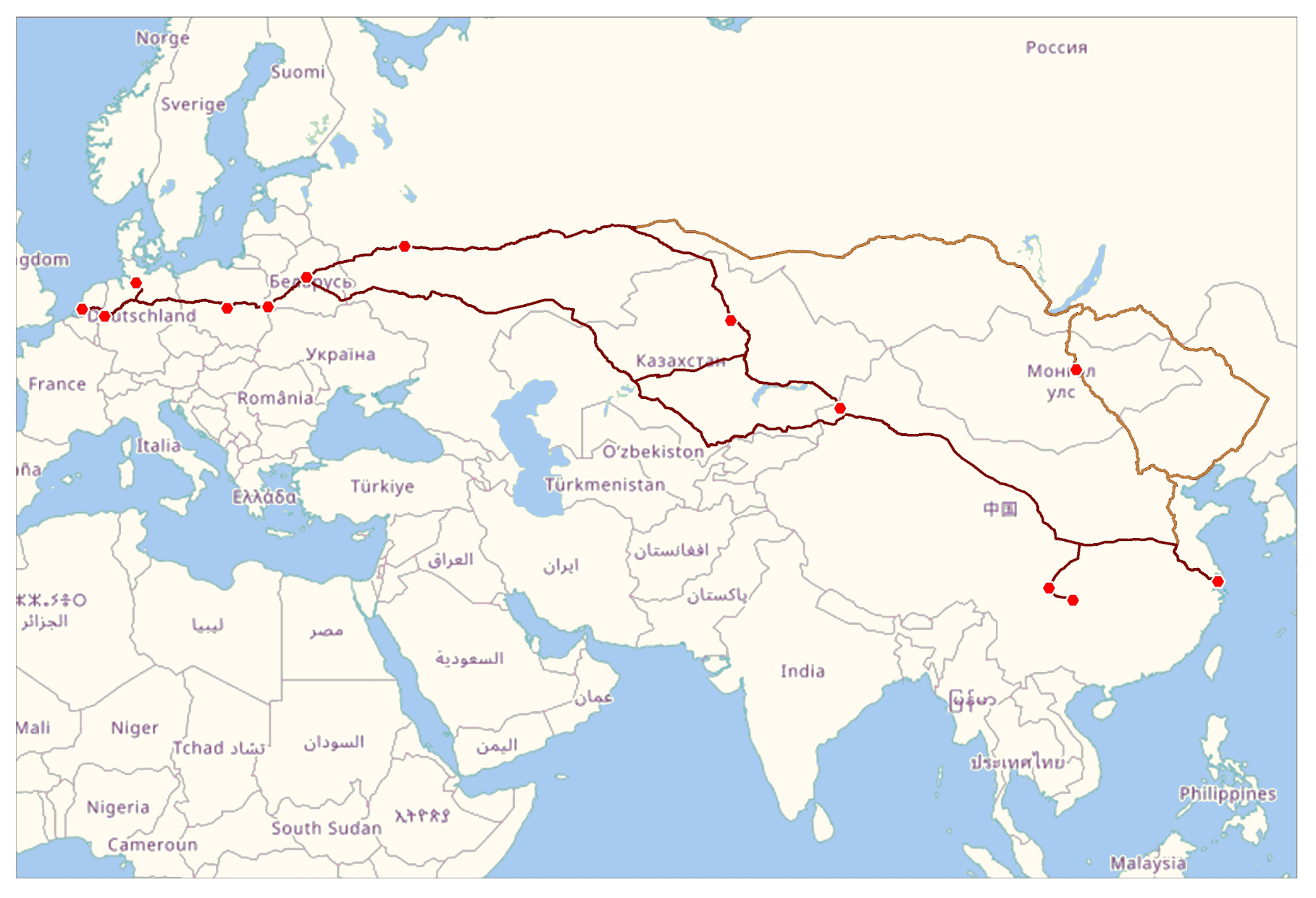

The most important intercontinental railway corridor, now and in the foreseeable future, connects the two continents through Poland, Belarus, Russia, and Kazakhstan. Departure points are a number of large cities in western China, including Xi’an, Chengdu, Chongqing, Yiwu, and Wuhan, whereas the most important destinations in Europe include Duisburg, Hamburg, Lodz, Tilburg, and also Moscow. Changes in railway gauge, and therefore transshipment handling, take place on the Polish-Belarusian border (typically Malaszewicze/Brest) and on the Kazakh-Chinese border (typically Dostyk/Alashankou or Khorgos).

From an economic perspective, railway transport is competitively positioned between ocean and air transportation. With lead times ideally some 20 days, rail is much faster than ocean, while cheaper than air freight. Therefore, the intercontinental corridor can be competitive for capital-intensive and time-sensitive products such as machine parts, electronics, perishable foodstuffs, etc. However, peak volumes reached over 2020 and 2021 could be partially explained by capacity shortages, obstructions, and subsequent higher tariffs in ocean freight, shifting to rail cargoes for which this more expensive option would normally not be justified.

Immediately after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, cargo volumes transported on the Eurasian corridor dropped sharply. For one, the insecure international circumstances, sanctions threat, and public awareness made many cargo owners reluctant to use the route. Another cause for the thinner flow is that Western sanctions forbade moving specific types of goods, including military and so-called “dual-use” products, into Russia and Belarus. Nevertheless, European operators so far have not been obstructed in buying services from Russian Railways (RZD).

Although the future seems less than certain, there are two main reasons for the relative insulation of railway services from Western sanctions. First, although their gusto for active participation in the BRI has mostly faded, EU member states, especially Germany, continue to attach great value to their trade relations with China. Second, as Russia serves as transit territory, inhibiting the route would likely not achieve significant damage to the Russian economy. As the costs of sanctioning the corridor outweigh the perceived benefits, European transporters are quietly allowed to continue their operations.

After the initial months of the war, volumes recovered to about half of their previous levels: over the whole of 2022 more than 400,000 TEUs were moved along these rail corridors. However, over the first half of 2023, the flow further decreased to some 114,000 containers, albeit with stable monthly volumes.

This might still seem more dramatic than it actually is: during 2022 ocean freight tariffs gradually recovered, relieving some of the earlier pressure on the railway corridor. Also, industry orders have reportedly fallen, leading to a decrease in demand. Therefore, current rail freight volumes might be closer to their natural state than it would seem at first glance.

China-Europe rail freight volume by year.

Evidently, cargo owners and railway operators in Europe and China would like to diversify their intercontinental services with alternative corridors, bypassing Russia. The so-called Middle Corridor transits Kazakhstan, the Caspian Sea, and Southern Caucasus; from there, southeast Europe can be reached through either Turkey or the Black Sea. Indeed, since 2022 a limited shift has taken place from one route to the other.

However, despite upgrades, capacity on the Middle Corridor will remain limited, and its complexity and longer lead times mostly prohibit a convincing business case. Although the Caspian route’s significance must certainly not be dismissed, its economic potential lies in facilitating the landlocked region’s own economic development and regionalization rather than accommodating large East-West flows.

The future of intercontinental rail freight seems undecided. Barring any targeted sanctioning of the Russian corridor by the EU, as long as the Ukraine conflict persists, setting up new services will remain a risky venture. On the other hand, the market has never experienced serious operational difficulties in Russia, while an increase in economic activity or a return to higher tariffs for ocean freight could lead to higher demand.

Indeed, European operators have reported a mutual understanding with their Chinese counterparts on continuing their focus on the northern route. Perhaps curiously, such an outlook also appears to be reflected by recent upgrades of the Malaszewicze border crossing, planned for a total of 800 million euros, under the auspices of the Polish government.

On balance, all hope may not be lost for this symbol of Eurasian connectivity.