When China’s National People’s Congress convened in March, President Xi Jinping stressed the importance of stability and security. But half a year later, the removal of Foreign Minister Qin Gang and Defense Minister Li Shangfu, as well as a purge of senior military officials, have made Xi’s new government appear neither stable nor secure.

Qin, last seen at a diplomatic gathering in late June, was removed without explanation in late July after weeks of official silence. Citing sources privy to internal party briefings, the Wall Street Journal reported in September that Qin was brought down by “lifestyle issues” – namely an affair during his time as China’s ambassador to the United States from July 2021 until January this year.

The Financial Times named his extramarital lover as Phoenix Television presenter Fu Xiaotian, who is believed to have had a child by surrogacy in the U.S. last year. (Fu is also rumored to have been a Chinese intelligence asset.) Her suspected affair with Qin and their presumed American-born son may have become known to the United States, thus compromising Qin in his new role as foreign minister.

Meanwhile, Li Shangfu was last seen at a China-Africa security conference in late August. Though not yet officially removed, he is believed to have been taken away for questioning, possibly as part of corruption investigations, according to another Wall Street Journal scoop.

In addition to Li, at least four generals from the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF) have been inexplicably ousted since June. The head of the PLA Military Court was also stood down in early September after just eight months in the post. While few details have yet emerged, the dismissals likely relate to an anti-corruption investigation at the PLARF, which has seen significant expansion in recent years.

In Li’s case, corruption charges could relate to his previous role at the Central Military Commission’s Equipment Development Department between 2017 and 2022. But, as with Qin Gang, there are also rumors that Li may have been compromised: specifically, that his son leaked classified information while studying in the United States.

While these various claims are unconfirmed, the purges are nonetheless remarkable. Coming within a year of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s 20th National Congress, an event marked by Xi’s total dominance of major government and military appointments, the removal of two key ministers raises many questions.

Were Li and Qin’s disciplinary issues not discovered during the vetting process for their ministerial roles? Were their misdeeds flagged and known to Xi, but he decided to appoint them anyway? Or is it possible that Qin and Li were purged not for indiscipline but for disloyalty, and how exactly might they have betrayed Xi’s trust?

These are complex questions to which we are unlikely to get clear answers any time soon. There are, however, some immediate conclusions that we can draw from the purge of the two ministers. Though there is no serious threat to Xi’s position, the purges are indicative of several challenges that he faces in managing senior political and military personnel – a deficiency of suitable talent, dissatisfactory performances, and internal divisions.

Despite winning a clean sweep of the top appointments at last year’s Party Congress, Xi appears to have lacked good options to fill key political and military roles. Qin Gang, for example, was less experienced than is typical for a ministerial appointment. But by appointing Qin, an outgoing U.S. ambassador, as foreign minister, Beijing was signaling an intention to focus on its most important bilateral relationship.

Recall that a previous contender for foreign minister, Le Yucheng, was shunned last year, likely because he is a Russia specialist who lacks U.S. experience (and was also seen to have mishandled relations with Moscow). That Wang Yi, a Japan expert who was foreign minister from 2013 to 2022, has now stepped back into the role, suggests a deficiency of more suitably specialized personnel in China’s foreign affairs system.

Wang, 69, is one of two veterans that Xi retained on the CCP’s Politburo past the conventional retirement age for senior officials, the other being Central Military Commission vice chairman and Xi ally Zhang Youxia, 73. These overage appointments indicate a dearth of younger candidates whom Xi deemed qualified to take charge of foreign and military affairs.

Qin and Li’s apparent dismissals likely also reflect Xi’s dissatisfaction with their performance in the short time since they were appointed. While Beijing may say that the two ministers were removed over corruption or other indiscipline, we should be skeptical of accepting such reasons as the sole cause of either Qin or Li’s downfall.

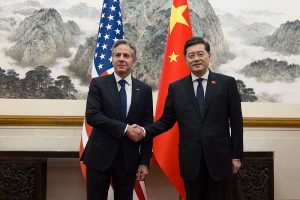

Rather, such misbehavior could in fact have come to light as a convenient pretext to dismiss two officials who had not performed as expected. In Qin’s case, he may have provoked Xi’s discontent by failing to effectively manage the U.S. relationship, perhaps because he was seen as being too soft on Washington. Indeed, Qin disappeared just one week after hosting a breakthrough visit from U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken; one of the earliest rumors regarding his dismissal was that Qin has somehow flubbed the crucial diplomatic exchange.

For Li, his handling of the Balloongate incident earlier this year appears to have been dissatisfactory. The New York Times, citing U.S. officials, reported that Xi became “enraged” after senior generals had kept him in the dark about the errant balloon, which wound up flying over the continental United States before being shot down by the U.S. military. The episode points to an absence of trust and transparency between Xi and sections of the military leadership.

Furthermore, the Qin Gang affair has revealed internal divisions within China’s political establishment. Qin’s rise is believed to have upset many in the Foreign Ministry, especially the “Wolf Warrior” diplomats like Zhao Lijian, whom Qin demoted two weeks after becoming minister. When it became clear that Qin was in trouble, Zhao’s wife seemed to express her delight in a thinly veiled Weibo post.

These events have been an unwanted distraction for China’s new government during its first half year, especially for the two ministries focused on managing Beijing’s external security apparatus. To be sure, Li and Qin’s removals have not noticeably affected Xi’s grip on political or military power. But the purges do reflect significant challenges for China’s leader in managing senior personnel.