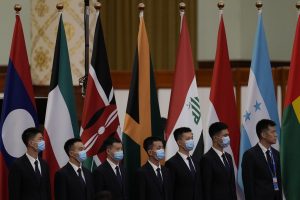

The third Belt and Road Forum (BRF), which doubled as a celebration of the tenth anniversary of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), was hosted in Beijing, China from October 17-18 2023. As with the previous BRF, Africa was well represented, with five heads of state or government attending from Kenya, Ethiopia, Republic of Congo, Mozambique, and Egypt, along with the vice president of Nigeria. Five top leaders from African countries attended the second BRF in 2019.

There has been much talk of a perceived slowdown in Chinese lending globally, and to Africa specifically, over the past few years, and of the BRI’s supposed pivot away from large scale infrastructure projects. Yet African leaders have not been content to swallow this narrative and instead continue to take opportunities to directly reinforce African development priorities with China, one of their key development partners. The BRF was another such opportunity, offering seemingly promising outcomes but with more work ahead for African countries.

With the dust now settled on the forum, were the priorities of African leaders taken into account?

To answer this question, it is important to first review the key BRF outcomes. Three stand out.

First, the money will keep flowing but will become more targeted, and green.

In his opening speech, President Xi Jinping indicated that China would continue to finance “signature projects,” but the BRI would also expand its focus to include “smaller yet smarter” projects, with greater emphasis on lower risk and more socially and environmentally impactful projects. The renewed commitment to signature projects in particular was accompanied by an announcement of over $100 billion in new funding for BRI cooperation projects from Chinese Development Finance Institutions (DFIs). Both the China Export and Import Bank and the China Development Bank will receive a new financing window of approximately $50 billion while the Silk Road Fund, also a part of the BRI financing mechanism, will receive a capital infusion of $10 billion.

The fact that the BRI’s pivot to “smaller but smarter” projects will not come at the expense of signature infrastructure projects, coupled with a new capital infusion for BRI projects, is a hopeful sign for African countries. With an estimated annual infrastructure financing gap of over $100 billion, funding for infrastructure development remains crucial for the continent’s growth prospects.

Second, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are getting a boost. At the forum, China Development Bank signed a Term Facility Agreement with the African Export-Import (Afrexim) Bank for a loan of $600 million to support SMEs in Africa. This funding seeks to promote economic cooperation between Afrexim Bank member states and China, as well as boost Africa’s export manufacturing capacity. This is important because there are an estimated 44 million SMEs across Africa, which drive economic growth and provide an estimated 80 percent of jobs across the continent.

Third, although hardly publicized, at the BRF China agreed to fund several infrastructure projects in a range of African countries. For instance, China will finance two major railway projects in Nigeria – the Abuja-Kano and Port-Harcourt-Maiduguri railways – at a cost of approximately $3 billion. A facility agreement was also signed for China to finance construction of a 25MW photovoltaic solar power plant in Burkina Faso. China also committed to fund the expansion of the Sagana-Marua highway in Kenya, the Niayes road, and improvement of the Dakar road network in Senegal (through China Development Bank), and, through the Silk Road Fund, China will invest in the Africa Investment Fund IV under the Old Mutual Fund based in South Africa.

However, although these appear to be promising outcomes for Africa, there is fine print to be aware of, and it will be important to continue to track post-BRF progress.

First, the pivot toward “smaller yet smarter” projects implies that Chinese lenders will aim for more green development and digital connectivity projects, as well as place greater emphasis on noneconomic aspects of projects, such as environmental and social impacts. Thus, to progress further African countries may well need to propose more of these types of projects to credible Chinese stakeholders and localize them. Panda Bonds, issued in Chinese capital markets and focusing focus on climate financing and sustainable development projects, can also be an option to explore. Egypt recently became the first African country to issue a Panda Bond.

Second, Xi also stated that the new funding for the BRI projects will be based on “business and market principles.” This language – China’s version of the “leveraging the private sector” rhetoric that is popular in development finance circles – sounds attractive, but it also means going forward, Chinese lenders are likely to emphasize commercial principles such as a low-risk appetite and preference for public-private partnerships (PPPs) relative to sovereign lending. But private sector financing – especially of basic utilities – can create significant problems for populations. Given fiscal space challenges, it may be better for African countries to work harder and more smartly to negotiate for longer term, and more concessional financing from China to meet their development needs.

Last but not least, this greater emphasis on commercial principles also means that Chinese lenders are likely to be more risk averse and require extensive due diligence for proposed projects than has been the case in the past. This is not to say that past projects financed by Chinese banks on the continent have been white elephants (we have not seen strong evidence for this), but it might mean harder work for African governments to prove project viability.

In this regard, and as we have previously argued, strong emphasis should be put on projects that promote regional integration, such as those under the African Union’s Program for Infrastructure Development for Africa (PIDA). Overall, regional, cross-country infrastructure projects are likely to have greater commercial viability as they take advantage of economies of scale provided by regional economic blocs as well as the broader African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). The Mombasa-Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway, recognized as an existing “flagship project” of the BRI, for instance, would have greater commercial viability if it is extended to Uganda, Rwanda, Tanzania, and South Sudan as originally conceived under the East-African Standard Gauge railway plan. Furthermore, given the current fiscal space challenges faced by many African countries, regional projects provide an opportunity for individual African countries to pool collateral for critical regional infrastructure.

Overall, the third BRF carried some optimism for African countries and their development aspirations with China’s new funding commitments for BRI cooperation projects as well as China’s renewed commitment to “signature projects.” However, and perhaps partly due to China’s own economic considerations as well as (unnecessary) calls from the G-7 and others for China to lend “more responsibly,” it seems African countries may well have to work harder to ensure the opportunities presented by the BRF enhance the continent’s economic growth and development.