Cambodia’s government has embarked on a diplomatic charm offensive aimed at luring back the Western goodwill and investors who were pushed out by an unprecedented influx of Chinese money and a crackdown on political opposition and the independent press that began in 2016.

The United States, Australia, Japan, France, and Germany are among the list of countries targeted with an unending stream of press releases and positive news stories in the local media highlighting strategic partnerships, and requests for aid packages, investors, and tourists.

Others include Thailand, Vietnam, and Georgia.

Cambodia’s economy is struggling despite official growth numbers of over five percent a year. Eighty percent of this country’s economy is embedded in the informal sector and a recent report from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) added some perspective, pointing out “significant” downside risks.

These included the economic slowdown in China, high private debt, climate change, and geopolitical tensions. The garment sector and tourism are the main drivers of the economy and, as the report noted, have not recovered, nor have Chinese investors returned.

It also said governance and anti-corruption reforms are “important” to attract new foreign investment adding it was “critical to strengthen frameworks on asset declarations, whistleblower protection, and access to information.”

“The compositional shift in tourist arrivals means the country is receiving less income per tourist compared to the pre-pandemic era,” it said. “Though the rebound has continued, downside risks are significant,” the executive IMF board warned.

Sources say government expectations that tourism numbers will return to the dizzying pre-COVID-19 levels by 2025 are being gently pushed back to 2028.

The IMF released its prognosis as Transparency International reported Cambodia had fallen eight spots to 158 out of 180 counties on its 2023 Corruption Perceptions Index and can now count itself in the bottom four of the Asia-Pacific, ahead of only Myanmar, Afghanistan, and North Korea.

Transparency International Executive Director Pech Pisey said Cambodia’s rank clearly points to “the persistence of grand and political corruption,” adding that the country’s fight against corruption had stagnated.

It’s an unfortunate ranking but hardly unexpected given last year’s one-sided election and the unwanted perceptions that were generated by human traffickers and the scam compounds that have earned Cambodia a notorious reputation over the last two years.

The U.S., United Kingdom, and Canada have imposed targeted sanctions on criminal elements.

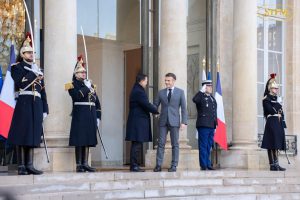

And for those reasons, French President Emmanuel Macron was criticized last month for hosting Prime Minister Hun Manet, who returned to Cambodia with a $235 million aid agreement focusing on drinking water, energy infrastructure development, and vocational training.

Cambodia, however, needs billions of legitimate dollars.

Even the government-friendly Khmer Times is reporting that “many commercial banks in the Kingdom, which have excess exposure to the real estate segment are facing crises, according to industry insiders.”

Sihanoukville and the south coast are littered with the skeletons of unfinished skyscrapers and infrastructure projects and Hun Manet’s government has offered investors tax breaks and generous visa extensions in a bid to reboot the construction sector while promoting economic reforms.

Hun Manet was handed power from his father Hun Sen in August but his government has shown few if any signs of shifting from the hardline political policies of the past and a long track record of blaming others for Cambodia’s misfortunes.

That includes wild and unsubstantiated allegations that the U.S. had backed opposition efforts to oust Hun Sen in an attempted coup, used to justify the banning of a political party, the jailing of more than 60 political prisoners, and the closure of independent media outlets.

In recent weeks government officials have made a habit of blaming an Al Jazeera report, “Forced to Scam: Cambodia’s Cyber Slaves,” broadcast in July 2022, for the poor image of Cambodia abroad.

But of course, that is to ignore the fact that it was neighboring countries, a very long list of NGOs and publications like the Khmer Times who blew the whistle on trafficking and scam compounds many months before Al Jazeera first aired its report.

Western dollars are desperately needed in Cambodia and beleaguered, cash-strapped local officials are now more than ready to throw down the welcome mat.

But any return is unlikely until there is a significant change in Cambodian attitudes, which puts an end to the made-up blame games of the past, deals effectively with corruption, and can promote Western interests, alongside those of the Chinese, should they also return.