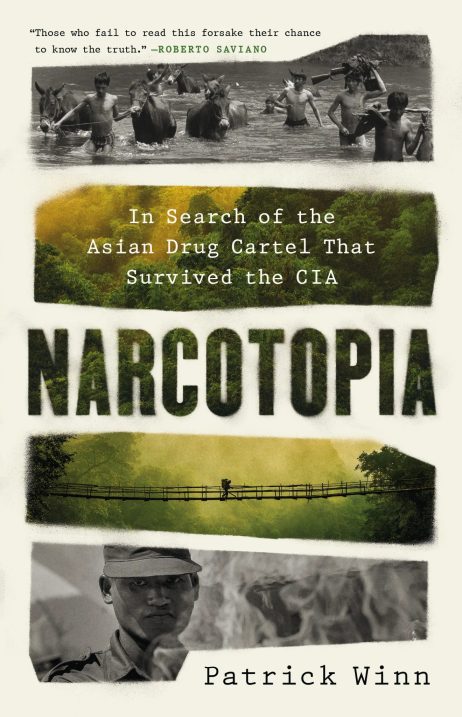

One of the few things that is widely known about Myanmar’s Wa State is the central role that it plays in Southeast Asia’s multibillion-dollar narcotics trade. But for the United Wa State Army (UWSA), the group that administers these two remote parcels of territory in Myanmar’s Shan State, drugs have been an engine not just of profit but of survival, helping Wa State transform itself into “a bona fide nation with its own laws, anthems, schools, and electricity grid” – one of the few truly independent ethnic states in Myanmar. In his new book, “Narcotopia: In Search of the Asian Drug Cartel That Survived the CIA,” Bangkok-based journalist Patrick Winn burrows into the history of the Wa, and explains how the region’s leaders have survived repeated cycles of political upheaval and international pressure.

Winn spoke with The Diplomat from Bangkok about the role that narcotic production plays in the political economy of Wa State, the region’s position in Myanmar’s post-coup conflict landscape, and its intricate connection to decades of U.S. anti-narcotics efforts.

One often sees the UWSA described in the media in sensationalized terms as a “narco-army,” but your book argues that the group is much more than a drug trafficking organization. Tell us a little about the relation of the drug trade to politics, business, and state-building in Wa State.

At this point, it’s absurd to pretend the UWSA is some drug-trafficking mafia and nothing more. Some of its leaders are wanted by the DEA, sure, but they’re running a full-on government with departments of health, agriculture, and finance. They build roads, operate an electrical grid, print license plates, and so on. Are they pleading for recognition from the United Nations? No, because Wa leaders know that would stir up more trouble than it’s worth. Outsiders have denigrated the Wa for centuries so they’re not too hung up on international acceptance.

But yes, Wa State is a narco-state. I mean that to sound no more pejorative than calling Saudi Arabia a petro-state. Since its founding 35 years ago, narcotics have served as Wa State’s financial engine, subsidizing everything from bullets to medicine to concrete – and making some Wa moguls rich along the way. But without heroin and meth, the state probably wouldn’t exist, and the Wa would be one more indigenous people preyed upon by Myanmar’s military.

Think of it as a state wrapped around a cartel. To be clear: these days, Wa commanders seldom oversee meth labs directly. They’d rather let Chinese syndicates run labs on their territory and charge rent. Outside syndicates also handle international trafficking — and that’s where you make the juiciest profits.

You describe in detail how the drug trade grew in Myanmar, Thailand, and Laos during the Cold War. Briefly, what role did U.S. policy play in stimulating the growth of this industry?

If forced to condense my answer into a single phrase: narco-espionage.

From the 1950s through the mid-1970s, the Central Intelligence Agency relied on opium smugglers to gather intel in tricky places. Namely in Communist China, Myanmar’s mountains, and in Laos. Traffickers are experts, after all, at sneaking about borders. These opium routes snaked up into the Wa homeland, which borders China.

Southeast Asia’s dominant cartel at the time was run by Chinese exiles, driven out of their country for opposing Mao Zedong. This group gave rise to the Golden Triangle drug trade as we know it today. They also aided the CIA and its junior partner, Taiwan’s military intelligence bureau, in sustaining radio listening posts, up in Wa country, that soaked up transmissions from China. Some Wa warlords – fearless men who were notorious in areas that still practiced headhunting – were recruited to raid China, steal files and wreak havoc. But it was the aforementioned cartel that held this narco-espionage system together.

In return, the agency would sometimes shield the cartel from criminal prosecution. Any drug-trafficking operation with near-immunity to arrest will thrive. And it did. Much of the heroin they produced – synthesized from opium harvested by the Wa and other indigenous peoples – found its way to South Vietnam and into the veins of U.S. troops.

While the U.S. empowered drug trafficking organizations and forces in mainland Southeast Asia as a bulwark against communism, the UWSA is a creature of the post-Cold War era, established following the collapse of the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) in 1989. How do the UWSA’s drug trafficking operations relate to Washington’s Cold War policies toward the region? How else has the political economy of drug trafficking in Wa State changed since the end of the Cold War?

We all know global communism crumbled in the late 1980s and early 1990s: the Berlin Wall came down, the Eastern Bloc disintegrated, the Soviet Union imploded. But few credit the Wa with liberating themselves from communists in 1989.

The Wa homeland was, for nearly two decades, ruled by the Communist Party of Burma – once a puppet organization with China pulling the strings. During the Cold War, it became one of the largest non-state communist forces on earth. But by the mid-1980s, even Beijing knew the party’s leaders were has-been Maoists who needed to go.

The Wa rose up, tossed out the sclerotic party and founded Wa State, retaking control of their homeland. It was, and is, a nation-inside-a-nation, nesting inside Myanmar. Myanmar’s military regime tolerated this because they already faced pro-democracy agitation in the lowlands and they couldn’t handle a beef with the Wa at the same time.

By the early 1990s, Wa State’s government needed a viable economy, so it was producing heroin for export – extremely pure, powder-white heroin. Much of it reached the world’s top marketplace for narcotics: America. Normally, this would’ve invited the DEA’s wrath, but instead something very unusual happened. There was an official high up in Wa State’s government – the principal source in my book – who approached the DEA. He presented an offer: the Wa would shut down their drug labs if the U.S. promised to help modernize their state with decent roads, schools and hospitals. This idea was pursued at the highest levels of the DEA and the UWSA.

Why didn’t this work out? The CIA sabotaged it. It’s a long saga, which I recount in “Narcotopia,” but post-Cold War politics play a role.

The CIA had its own agenda in Myanmar. The spy agency, along with the State Department, was determined to enfeeble Myanmar’s regime. After the Soviet Union collapsed, the U.S. was “running out of demons,” as Colin Powell put it. And in the words of one U.S. diplomat, Myanmar was a “cat to kick” – a perfect sponge for the West’s human rights campaigns, because its regime was truly loathsome.

The CIA had its own agenda in Myanmar. The spy agency, along with the State Department, was determined to enfeeble Myanmar’s regime. After the Soviet Union collapsed, the U.S. was “running out of demons,” as Colin Powell put it. And in the words of one U.S. diplomat, Myanmar was a “cat to kick” – a perfect sponge for the West’s human rights campaigns, because its regime was truly loathsome.

The DEA, meanwhile, was friendly with Myanmar’s military. That’s how the DEA operates. It teams up with cops and troops in a “host country” such as Mexico and Colombia. The DEA was giving Myanmar’s regime a role to play in its grand Wa drug-eradication proposal. This Wa-DEA deal would’ve cratered the country’s heroin supply and turned the pariah regime into drug war heroes — and the CIA and State Department could not tolerate this. In the end, the intelligence folks won the day, as they usually do, and the DEA reverted to treating the UWSA like a drug cartel.

In discussions of Myanmar’s ongoing conflict, not a lot has been said about the UWSA, which has remained mostly on the sidelines since the 2021 coup. How has the group approached the post-coup violence? What do you think its current goals are, and is there any principle at play beyond mercenary self-interest?

Wa State’s leaders have goals similar to those in other small states such as Laos: acquire more infrastructure, try to build the economy, and ensure the supremacy of the ruling class. In Wa State, this means the UWSA’s highest echelon, which is dominated by a few families. The continued existence of the state – the homeland of the Wa people – is their highest priority. And they’re achieving it, despite the fact that many of the aging leaders didn’t finish middle school. You can’t deny their political savvy.

Few will admit this but the most stable government in Myanmar isn’t the one run by the military. It’s Wa State. There are no bombs raining down on the Wa nor any battles in its hills. I believe Wa State will exist in 30 years. Will the military regime survive five more years? I’m not so sure.

In Myanmar’s revolutionary war, the UWSA likes to play big brother to its indigenous allies – the Ta’ang, the Kokang, the Arakan – but it sees no benefit from direct conflict. They’ve already achieved what many ethnic minority groups dream about: a state of their own. No matter who prevails in the end, the UWSA will turn to the winner and say: congrats, same deal as before? We operate our own state inside Myanmar and you keep a polite distance? The victor will accept these terms because no one wants to tangle with the Wa.

One issue that has attracted more attention is the UWSA’s relationship to China, given geographic proximity, the close relationship between Beijing and UWSA’s precursor, the CPB, and the fact that the UWSA’s leadership is predominantly Han Chinese. How do you think the Chinese authorities view the Wa, and how would you characterize their relationship with the group?

I’d call it a client state of China. Not a puppet state – you can only push the Wa so far – but the leaders, before making key decisions, will ask themselves: is this going to upset Beijing? I’m sure countries in America’s orbit ask similar questions about Washington.

The close relationship between the Wa and Chinese governments isn’t hidden. Some people might struggle to believe that Chinese officials appointed by Xi Jinping routinely go into the mountains to meet men indicted by the DEA. It sounds like a conspiracy theory. But there are photos, taken at public ceremonies, of Chinese diplomats next to Bao Youxiang, Wa State’s supreme leader. It’s out in the open.

For China, allying with the giant narco-state next door offers huge perks. A former senior Wa officer explained to me that narcotics synthesized on Wa terrain are forbidden – by the UWSA – from flowing into China. They instead pour south into Thailand, which also shares a border with Wa State, and onward to other parts of Southeast Asia, some reaching Australia. Contrast that with the DEA’s strategy on the U.S.-Mexico border: attempt to smash up the cartels, arrest their leaders, seize their drugs ad infinitum. This creates power vacuums. Smaller cartels rush to fill them and the most vicious get the spoils. It’s a nightmare.

I’m not arguing that the U.S. should copy this model and befriend Mexican cartels – unlike Wa State, they’re just profit-seeking machines with no larger agenda – but China certainly benefits from treating Wa State like a state, not a mafia group. I also believe that China has enough leverage to make the UWSA reduce the volume of meth synthesized in their state.

A lot of time and effort and resources have been spent on trying to stem and interdict the flow of drugs from Wa State and other parts of eastern Myanmar – yet trafficking and seizures continue to rise. Given the nature of how drugs function in the political economy of Wa State and other regions, how in your view should the region’s governments, and partners like the U.S., approach this issue?

The War on Drugs passed the half-decade mark last year and, despite not delivering on its promises, it’s just chugging along on auto-pilot. The DEA used to talk tough about the Wa, calling it a “tribal violent group” and vowing to team up with “international partners to disrupt and dismantle these dangerous criminal syndicates” but the idea of dismantling the UWSA is a joke. It’s an army with 30,000 troops. I’ve spent time with some intelligent, capable former DEA agents. Few if any believe they’ll ever touch the indicted UWSA officials.

All the U.S. and its drug war ally, Thailand, can do is try to quarantine Wa State. To ban it from the global financial system. We all know the U.S. can treat corporations as people, right? America also has a law called the Kingpin Act that can designate an entire drug-trafficking organization as a “kingpin.” So if you have exposure to U.S. banks, and you engage in any transaction with someone from the Wa government – tens of thousands of Wa people from nurses to accountants to truck drivers to commanders – then you’ve polluted the U.S. banking system with filthy drug money. And you risk punishment.

The U.S. declared the UWSA a “kingpin” more than two decades ago. You don’t have to be a policy wizard to guess the effect of this strategy. It makes pivoting into legal economic enterprise extremely difficult. Other major revenue generators for Wa State have been rubber and tin, both sold to China, but I doubt the profits are enough to sustain the entire state.

Look, narcotics embarrass the leadership and they do not allow drug use among their own people. But Wa State – all 30,000 square kilometers of it – is mostly harsh mountainous terrain, far from major population centers. It’s never going to become an agricultural or manufacturing powerhouse.

So meth it is. I think that if you sent the finest Harvard- and Eton-educated economists to Wa State and forced them to come up with an alternative to narcotics, they’d fail. Within a week, they’d throw up their hands and say, sorry, the meth labs have to stay. Operating a nation-state isn’t free and drugs pay the bills like nothing else.