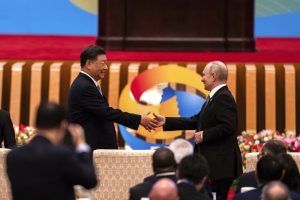

When the Kremlin announced that Vladimir Putin’s first trip abroad in his fifth presidential term would be to China, it came as no surprise to the global policy community. Xi Jinping had likewise made Russia the destination of his first foreign trip after being appointed Chinese president for a third term in March 2023.

Both leaders clearly value the symbolism of these reciprocal visits, which underscore the depth of the Sino-Russian partnership. Given the leader-driven, top-down nature of politics in both Beijing and Moscow, regular face-to-face interaction between Xi and Putin is also of great practical importance for both sides.

Both leaders appear to have much to celebrate when Putin arrives in Beijing on May 16, as China-Russia ties have continued to develop strongly. Bilateral trade has grown handsomely since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, soaring from $146.9 billion in 2021 to $190.3 billion in 2022 and $240.1 billion in 2023. This has provided Moscow with an indispensable export outlet and revenue stream and supplied it with otherwise hard-to-obtain replacement technological products.

If, at any point in 2022-23, Xi had doubts about the prudence of his deepening strategic cooperation with Putin – while Russia’s military was experiencing setbacks in Ukraine and Putin’s own rule at home was imperiled by a short-lived mercenary revolt – he probably feels more assured about his decision now. Russia’s military has begun to operate more effectively and has achieved continuous battlefield gains in recent months, amid a growing war fatigue in Ukraine and divisions in the West about the extent of military support Kyiv should receive.

What’s more, the domestic stability of Putin’s rule has been bolstered following the smooth completion of Russia’s 2024 presidential election. While it was essentially a stage-managed event, the election marked a time of heightened apprehension in the Kremlin during which Russian politics was temporarily focusing inwards. With this “technical” hurdle now cleared (and a military defeat in Ukraine seemingly averted), China appears convinced that Putin will remain firmly in power in Russia for the foreseeable future. Chinese media have continued to amplify Russian official narratives about Ukraine, for instance by echoing the Kremlin’s reports regarding Kyiv’s alleged involvement in the March 2024 terrorist attacks in Moscow.

Chinese Supplies Under Scrutiny

This broader deepening of Sino-Russian ties notwithstanding, problems have been accumulating in bilateral relations in recent months, as Beijing has been exposed to growing scrutiny and increasingly vocal criticism from Western governments concerning its role in the Ukraine conflict. When China’s special envoy on Ukraine, Li Hui, traveled to Europe in March to engage in lackluster peacebuilding talks, he received a markedly cold reception there. In all European capitals he visited, Li was reminded that China’s (indirect) support for Russia is actively hurting Sino-European ties. During their recent in-person meetings, EU leaders communicated this point directly to Xi. Similarly, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, during her visit to China in April, devoted much of her time and attention to criticizing Beijing’s ties with Moscow, as did U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken during his own China visit later that month.

China’s growing tensions with Western states are primarily linked to Beijing’s continued military cooperation with Russia. In spite of international concern about the invasion of Ukraine, Sino-Russian cooperation in the military sphere, particularly in the form of joint maneuvers, aerial and maritime patrols, has considerably intensified since February 2022. During a four-day official visit to Moscow in April 2023, China’s then-Defense Minister Gen. Li Shangfu announced that both countries will “expand military cooperation, military-technical ties and arms trade,” adding that “we will certainly take them to a new level.”

Throughout 2022 and 2023, Russia’s military was frequently running short on ammunition and other basic supplies, but as Moscow has revitalized its military-industrial complex, the supplies it now needs most are specific dual-use components. These are things China can provide, and which are difficult to trace, including machine tools, drone and turbojet engines, and various kinds of semiconductors and microelectronics. These base components are classic dual-use items that are particularly hard to distinguish from components for civilian production.

Customs records from 2022 and 2023 depict what appears to have been a well-concealed but steady stream of dual-use goods (such as drones), but also more evidently combat-related items (such as gunpowder, assault weapons, body armor, or thermal optical sights) flowing from China into Russia. By early 2023, U.S. intelligence sources and senior government officials asserted that China’s Central Military Commission, which is led by Xi, had greenlit the covert delivery of weapons, including ammunition and artillery supplies, to Russia. Around the same time, Ukraine reported finding a steadily growing number of Chinese components in Russian weapons, as well as Chinese-produced ammunition, on the battlefield.

In early 2024, Blinken asserted that China continues to provide materials to support Russia’s defense industrial base, while other senior U.S. officials have claimed that, according to U.S. intelligence findings, China has been making a “massive effort” to support Russia’s war effort “that ranges from geospatial assistance for Russian targeting to dual-use optics and propellants used in everything from tanks to missiles.” Beijing has firmly denied all of these allegations.

While China is not officially supporting Russia in the Ukraine war and continues to plead neutrality, Beijing would almost certainly like to see Moscow emerge victorious, since this would serve as a deterrent against future U.S. strategic expansion eastward and a reaffirmation of Russia’s great power status. China and Russia have considerable joint geopolitical interests, and opposition to NATO has become a growing strategic focus for Beijing in recent years.

Beijing’s Balancing Act

European leaders, for whom Russia’s war of conquest in Ukraine represents a critical security concern, have very vocally tried to persuade Xi to use his leverage on Russia to act as a mediator in the conflict. At the same time, however, they appear to be increasingly convinced that this might be a futile effort.

Although Beijing has occasionally dispatched a special envoy to Ukraine and Europe to demonstrate some willingness to mediate, in practice Xi has refused to play a proactive role in resolving the conflict. He has barely engaged with the Ukrainian government at all, while demonstratively cultivating his close relations with Moscow. Chinese officials have frequently refused to interact with Ukrainian diplomats (including Ukraine’s ambassador to Beijing), apparently avoiding direct engagement with them on purpose.

In recent months, Western governments have been unprecedentedly explicit in communicating to Beijing that they perceive its support for Russia as compromising core European security interests and that it is actively hurting China’s relations with Europe. It remains unclear if such warnings will lead to any substantial policy changes in Beijing, which has shown no interest in distancing itself from Moscow, as long as it can uphold a thin veneer of diplomatic neutrality regarding the conflict in Ukraine. Instead of making tangible concessions to their Western critics, Chinese officials have so far tried to deflect the blame for the ongoing bloodshed in Ukraine away from China (and Russia) and toward the United States. While insisting that it is providing no lethal aid to Russia, Beijing appears relatively convinced that it can maintain plausible deniability with regard to the supply of more ambiguous dual-use items.

At the same time, however, Beijing is clearly trying to reach out to its critical trade partners in the West, especially in Europe. Xi has been trying to cultivate goodwill in Western capitals, as he is trying to avert the outbreak of a full-blown trade war with the European Union over accusations of unfair trade practices, particularly regarding Chinese state subsidies for green technology producers of electric vehicles, solar panels, and wind turbines. China is therefore trying to keep a balance between providing some form of support to Moscow and not seriously damaging its relations with the West, but this balancing act seems to be increasingly difficult.

In December 2023, Washington imposed new sanctions on hundreds of people and entities, including in China, a move that has visibly hampered Sino-Russian trade, as Chinese financial institutions in particular now have growing concerns about being targeted by secondary sanctions. Since the beginning of 2024, Chinese credit institutions have begun to close many accounts of Russian companies and have also sharply tightened checks on payment transactions, forcing businesses to use “underground channels” with intermediaries in third countries.

According to recent Russian press reports based on customs data, China’s exports to Russia declined year-on-year for the second consecutive month in April 2024, following consistent growth in the months prior, which is likely related to U.S. sanctions threats against Chinese banks. Much of this decline has been attributable to reduced trade in potentially sensitive dual-use goods. Consequently, it appears that for Putin one important point of his discussions with Xi during his visit to China is to find a solution to the problem of bank payments in Sino-Russian trade.

In addition, other problems have been rearing their heads in bilateral economic interaction that are unrelated to Western sanctions. For instance, some Russian industrialists, including the president of the major automobile company AvtoVAZ, have recently voiced complaints about cheap Chinese industrial products flooding the Russian market and the unwillingness of Chinese carmakers to involve Russian suppliers.

Navigating these and other complications for Sino-Russian cooperation looks set to become even more difficult as time progresses. Amid the diplomatic pomp and circumstances of Putin’s state visit, both leaders have many thorny issues to discuss.