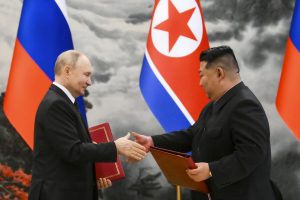

Russia and North Korea signed a new treaty elevating their relationship to a comprehensive strategic partnership during Russian President Vladimir Putin’s visit to Pyongyang on June 19. It’s the first formal blueprint for North Korea-Russia relations issued since 2001, and renews the mutual defense commitments made in the North Korea-Soviet Union treaty of 1961.

According to TASS, Russia’s state-owned news agency, “Russian Presidential Aide Yury Ushakov explained… the new document is needed because of profound changes in the geopolitical situation in the region and worldwide and in bilateral ties between Russia and North Korea.”

Putin himself hailed the treaty as “a truly groundbreaking document that reflects the desire of the two countries not to rest on their laurels, but to bring our relations to a new qualitative level.”

According to the Russian leader, the new treaty sets ambitious tasks and benchmarks for expanding the relationship in the “political, trade and investment, cultural, humanitarian and security spheres.” Bilateral ties have already made big advances in these areas since North Korean leader Kim Jong Un visited Russia in September 2023.

On the political front, the Kim-Putin summit last year kicked off a flurry of bilateral exchanges, including visits to North Korea by Russia’s foreign and defense ministers. According to Reuters, citing South Korea’s Unification Ministry, Russia and North Korea “have exchanged more than two dozen high-level government, parliamentary and other delegations since July 2023 – including 18 this year – which marks the highest-ever number of such visits.”

As for economic cooperation, Putin noted that “trade turnover increased 9-fold” in 2023 and “increased by another 54 percent” in the first five months of 2024. He admitted, however, that this growth was coming from a very low starting point, and overall figures remain “modest.” Neither Russia nor North Korea publicly releases their trade data.

Much of the trade presumably involves sales of ammunition and other defense materiel from North Korea to Russia, for use in its ongoing invasion of Ukraine. Such arms sales are in violation of previous U.N. sanctions in response to North Korea’s nuclear and missile tests, but Russia is not losing any sleep over breaking the restrictions. In fact, Putin dismissed the U.N. sanctions as an “indefinite restrictive regime… inspired by the United States and its allies” and urged that the sanctions “must be revised.”

In exchange for North Korean arms, Russia is believed to be providing food and energy supplies, as well as technical assistance and advice to bolster North Korea’s development of spy satellites and nuclear-capable submarines.

Korean Central New Agency (KCNA), North Korea’s main mouthpiece, said Putin’s visit was a testament to the “invincibility and durability of the DPRK-Russia friendship and unity” (DPRK is an abbreviation for North Korea’s formal name, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea).

As a sign of the importance accorded by Pyongyang to Putin’s visit, Kim Jong Un came to the airport personally to meet Putin upon his arrival. Kim also rode in the Russian president’s private car to accompany him to his rooms at Kumsusan State Guest House. KCNA emphasized the intimate nature of their private conversation: “the top leaders exchanged their pent-up inmost thoughts and opened their minds to more surely develop the DPRK-Russia relations.”

Kim lavished praise on Putin, calling him “the dearest friend of the Korean people.” But for all the comments about personal “friendship,” the geopolitics were never far from the picture. Kim was well aware that, as he put it in comments after the signing of the treaty, “the whole world turn[ed] its eyes to Pyongyang” to watch Putin’s visit.

Indeed, the coverage of the meeting made clear that Pyongyang is eager to play a more active role on the world stage, rather than being relegated to the status of a regional player.

The “friendly relations” between North Korea and Russia “have emerged as a strong strategic fortress for preserving international justice, peace and security and an engine for accelerating the building of a new multipolar world,” KCNA declared. In other words, Pyongyang is positioning itself along Moscow as a key player in remaking the international order.

As part of that ambition, North Korean media devoted special attention to the supposed U.S. “threat” to faraway Europe. The Pyongyang Times devoted a separate article to Putin’s comments, made in a meeting at the North Korean Foreign Ministry, that the United States is “the major threat to Europe.”

This serves to justify North Korea’s “full support” for Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine. Under this framing, it’s no longer an opportunistic partnership – arms for badly needed food and energy – but a strategic gambit to remake the international order. Pyongyang wants to be seen as a global player, on equal footing with Russia in the development of a “new multipolar world.”

In that context, it was curious that neither side mentioned China, which has also vowed repeatedly to usher in a new “democratic” multipolar world. The joint statement issued after Putin’s visit to Beijing in May used similar language. The three would seem to be natural partners in this endeavor, and there has been much talk of a China-North Korea-Russia “axis,” or even a full-fledged defense alliance.

But in reality, Beijing seems to have little interest in formalizing a trilateral partnership. China seems wary of the reputational costs joining hands with North Korea would entail; compared to Moscow, which has little to lose, Beijing has undertaken far fewer high-level exchanges with Pyongyang over the past year.

As Wooyeal Paik pointed out in a previous article for The Diplomat, China also has good reason to be wary of North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs, which risk destabilizing China’s own region – and, at the very least, bringing more U.S. military presence to China’s doorstep. Russia would consider this a benefit; for China, the calculation is quite different. Moscow’s assistance to Pyongyang in this regard is not a clear-cut win for Beijing.

Due to these concerns, China has kept discussions of a full-fledged trilateral partnership at bay. For instance, South Korea’s intelligence agency believes that Russia and North Korea expressed interest in trilateral naval exercises with China in 2023. This has yet to eventuate, however, suggesting the idea was quietly dismissed by Beijing.

And even as North Korea-Russia trade boomed, China-North Korea trade figures declined each month from January to May 2024. According to NK News, “Every month this year has seen a lower volume of [China-North Korea] bilateral trade compared to the same months in 2023, with the total on-year decline through the first five months reaching $30.8 million.”

In another sign of divergence, while Putin was in Pyongyang, Chinese officials were in Seoul to conduct the first “2+2” diplomatic and security dialogue at the vice-ministerial level. During the talks, China and South Korea agreed to promote the “healthy and stable development of the China-South Korea strategic cooperative partnership.” On North Korea issues specifically, China’s delegation emphasized the importance of “safeguarding peace and stability on the Peninsula” and “avoid[ing] escalation of confrontation and rivalry.”

China’s only comment on Putin’s visit to North Korea was that the two countries, “as friendly and close neighbors, have the legitimate need for exchanges, cooperation and development of relations.” Other than that, Chinese officials demurred by describing the trip as a purely “bilateral arrangement.”

The Chinese readout took pains to note that the timing of its 2+2 with South Korea was coincidental and “has no particular connection with exchanges between other countries,” but the parallel diplomacy nonetheless served to highlight the divergence between China’s approach to the Korean Peninsula and Russia’s. It’s impossible to imagine Russia hosting a similar diplomatic exchange with South Korea in the current context.

With China not overly interested in formalizing trilateral cooperation, North Korea and Russia will push forward on their own.