Russian President Vladimir Putin’s first visit to Pyongyang in 24 years attracted widespread attention. Most headlines focused on the fact that Putin and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un signed the Treaty on Comprehensive Strategic Partnership between the DPRK and the Russian Federation, the most significant and far-reaching agreement between the two states in the post-Cold War era, which further strengthened Russia North Korea relations. Receiving far less fanfare, however, was another breakthrough.

The two sides also signed an intergovernmental agreement on the construction of a cross-border road bridge across the Tumen River involving China, Russia, and North Korea. There is a railway bridge over the Tumen River, connecting Russia and North Korea. However, the bridge, built in the early days of the Cold War, is only 9-meters high. As a result, it hinders further development and utilization of the Tumen River by commercial ships from various countries in Northeast Asia.

The Tumen River, flowing through China, North Korea, and Russia, has long been the focus of geopolitics in Northeast Asia. This is not only the natural border of the three countries, but also provides a potential sea outlet for China to reach the Sea of Japan after passing through the section of the river bordered by Russia and North Korea. However, for a long time, due to complex reasons from various parties involved, including historical legacy issues and constraints from current political factors, the strategic value of this river has not been fully realized.

During Putin’s visit to Beijing in May 2024, China and Russia reached an agreement on the issue of the Tumen River estuary. Both sides explicitly stated in a joint statement that they will engage in constructive dialogue with North Korea regarding Russia’s support for Chinese ships sailing downstream on the Tumen River. In June, during his visit to North Korea, Putin announced that he would build a new road and railway bridge on the Tumen River, which could serve as a replacement and supplement to the railway bridge. However, it remains to be seen whether the existing bridge will be rebuilt and elevated, or abandoned and replaced.

What does all this mean for Mongolia?

Some content of the recent Russia-North Korea treaty is similar to the treaty signed between Russia and Mongolia in 2019. But Russia signed these two international treaties at different times, and under different conditions in the Asia-Pacific region and the world.

In 2019, Ulaanbaatar hoped to elevate the awkward bilateral cooperation between Mongolia and Russia, which had been stagnant for nearly 30 years since the disintegration of the Soviet Union, to a higher level, balancing with the rapidly growing relationship with China. At present, compared to its relationship with China, Mongolia’s wishes have not been fully realized.

On one hand, the political and security impact of Russia in Ulaanbaatar is increasing compared to before. Russia aims to contain, restrict, and control Mongolia’s relatively free and active “third neighbor policy” and diplomatic activities, especially amid Russia’s own isolation following the Ukraine war. On the other hand, Mongolia’s economic and trade relationship with Russia remains the same. Foreign exchange payments are made to Moscow every year from coal, copper, and other mining industries in the southern Gobi region that are not easily obtained. The Mongolian people are not very satisfied with this long-standing imbalanced trade relationship with Russia.

Against that backdrop, a breakthrough in trade and transit between China, North Korea, and Russia, could have major implications for Mongolia by opening up access to North Korean seaports via the long-dreamed-of “Two Mountains” Railway.

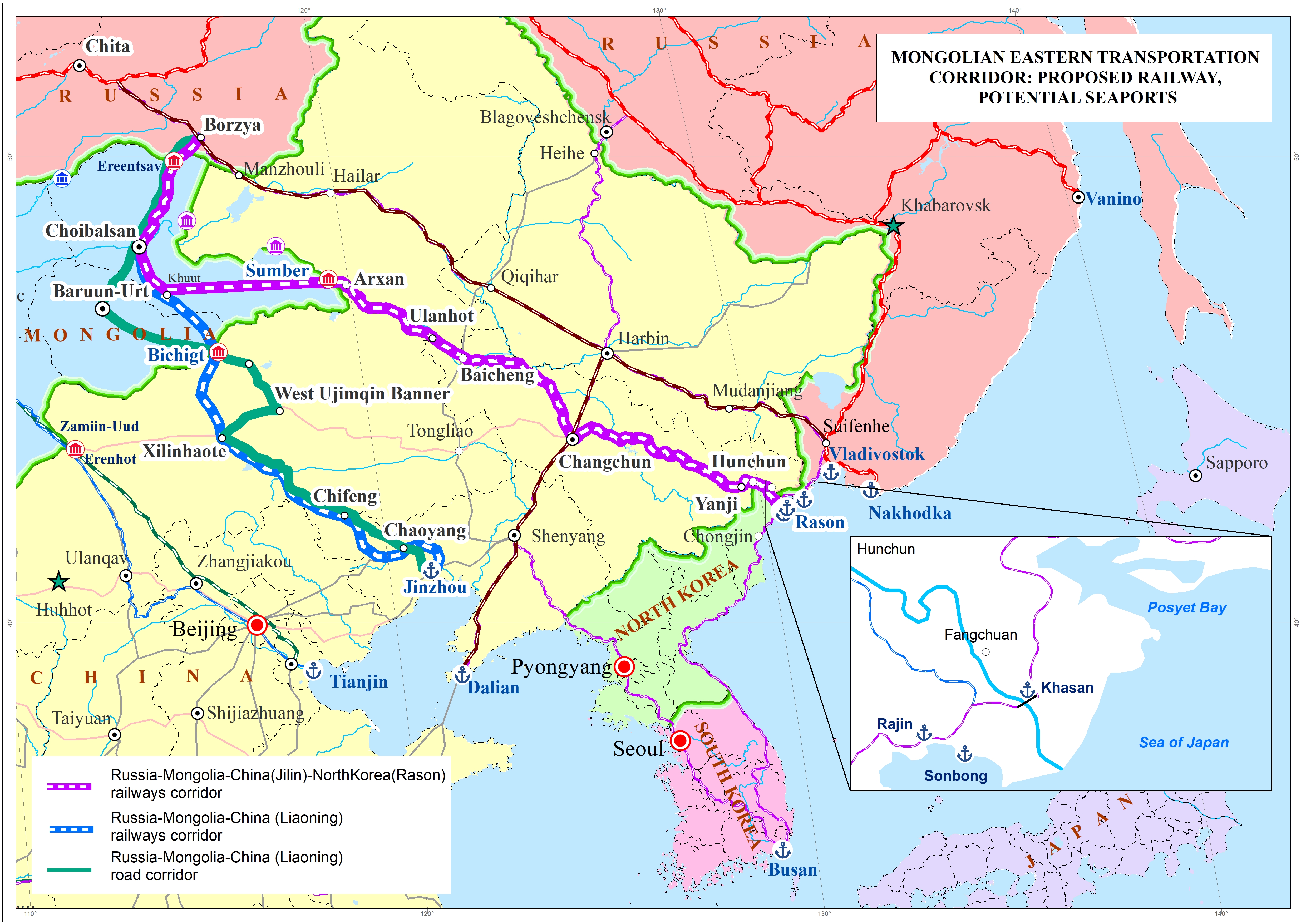

The Choibalsan-Arxan Railway – also known as the Two Mountains Railway – is an international railway to be built, connecting the city of Arxan in Inner Mongolia, China, and Choibalsan in the Dornod province of Mongolia. The Soviet Union first proposed the idea of building the Two Mountains Railway, but it was later shelved due to the Sino-Soviet split. As early as the late 1980s, however, Jilin Province revived the idea when it proposed the concept of constructing the China-Mongolia Railway Corridor.

In the early 1990s, the Two Mountains Railway rose again in the United Nations Development Program’s promotion of cooperative development in the Tumen River region. This proposal received support from relevant departments of China’s State Council.

According to a preliminary Chinese budget plan from around 2015, the total length of the Two Mountains Railway is 476 kilometers, with an estimated total investment of 14.2 billion yuan (about $2 billion), including 20 stations, 80,000 square meters of factory buildings, 25 bridges, and 445 meters of culverts. The railway will have a cargo flow density of 15-25 million tons per year, an annual return rate of 8.1 percent, and an investment payback period of 14.8 years. From exploration, design, to construction, it is expected to take approximately three years to complete.

The Outline Plan for Building the China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor, which envisions linking landlocked Mongolia to seaports in Russia as well as North Korea, also includes plans for the Two Mountains Railway.

However, due to the weak economic strength in the Baikal Lake region of Russia, the eastern provinces of Mongolia, Jilin Province of China, and the eastern regions of Inner Mongolia, the Two Mountain Railway has not been completed due to insufficient resources, financial resources, and freight capacity. Accelerating railway construction is of great significance for the current implementation of cross-border economic cooperation in Northeast Asia. If the construction of the Two Mountains Railway can be completed, it can solidify the Tumen River international transportation corridor from Chita in Zhabaikalski Krai, Russia, to Choibalsan, Mongolia, Hunchun in Jilin Province, China, and finally the seaport of Rason, North Korea.

Now the tides seem to be turning in the long-stalled railway’s favor. Since the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the relationship between Russia and China has been warming up. Bilateral trade has been soaring year by year, and the number of transit goods has increased. There are bottlenecks and deficiencies in the current transit and transportation system areas such as Erenhot, Manzhouli, and Suifenhe, and new transportation corridors need to be constructed. The new trade channels will likely transit Mongolia: either reaching ports such as Jinzhou and Dalian in China’s Liaoning Province from Chita, Russia, through Mongolia, or as mentioned above, traveling from from Chita through Dornod (Mongolia) and Tumen River corridor to arrive at North Korean ports.

Map courtesy of the Institute of Geography and Geoecology, Mongolian Academy of Sciences. Altanbagana and Urantamir

This would be the fulfillment of over two decades of dialogue. Around mid-2000, during the meeting of the Consultative Committee between the governments of North Korea and Mongolia, North Korean representatives proposed to allow Mongolia to invest and cooperate in the Rason Special Economic Zone, as well as the use of North Korean ports. From April 20 to 22, 2010, during the visit of then-Mongolian Foreign Minister Gombojav Zandanshatar to North Korea, he inspected the operation of the Rason Special Economic Zone and Rajin Port. Subsequently, the North Korean government expressed its willingness to provide favorable conditions for Mongolia to use the Rajin port and requested the establishment of a trade, service, and tourism representative office for Mongolia in the Rason Special Economic Zone. Later, Mongolia’s Deputy Minister of Roads, Transport, Construction and Urban Development Amarjargal Gansukh signed a memorandum of understanding with the North Korean side in Pyongyang regarding the joint use of the Rajin port.

From February 22-25, 2015, then-North Korean Foreign Minister Ri Su Yong paid a visit to Mongolia. One of the important issues discussed by both sides during the visit was the export of coal from Mongolia to third countries through North Korean ports. At that time, media reported that Mongolia would transport 25,000 tons of coal to Rajin port in 2015. Specifically, the coal would be transported to North Korea’s port via the Mongolian-Russian joint venture Ulaanbaatar Railway.

In 2018, the governments of Mongolia and Russia signed an Agreement on Terms of Transit Transport by Railway. According to the agreement, for 25 years Mongolia can enjoy stable tariff discounts when transporting its exported goods through Russian territory to third countries. Under this agreement, Mongolian mineral resources can be delivered to North Korean ports on favorable terms through Russian railways, and exported from there to countries such as China, Japan, South Korea, and India.

However, implementation still has not materialized. In 2022, during the COVID-19 pandemic, when North Korea completely shut its borders, then-Mongolian Transportation Minister Khaltar Luvsan stated that North Korea’s Rajin port was still a possible option for Mongolian exports in the future. Due to the impact of the pandemic, however, there were no opportunities to meet and talk with the North Korean side. The minister remained optimistic that once the pandemic improved, Mongolia could cooperate with representatives from the railway departments of Russia and China to realize Mongolia’s access to Rajin port in North Korea.

With China, North Korea, and Russia now solidifying their trilateral transportation network, the time is ripe for Mongolia to realized its long-held goal.

Russia’s Eastern Economic Forum will be held from September 3 to 6 in Vladivostok. The theme will be to strengthen cooperation in the Asia Pacific region and the development of the Arctic and Far East. Given the frequent cooperation between Russia and China, improved relations between Russia and North Korea, and Putin’s visit to Pyongyang, we may see high-level leaders from countries around East Asia visiting Vladivostok for the forum. Mongolian President Khurelsukh Ukhnaa may attend the Eastern Economic Forum for discussions advancing this transport corridor. He may even choose to visit Pyongyang to meet with Kim Jong Un to strengthen bilateral cooperation, especially Mongolia’s use of North Korean ports.

How the situation evolves remains to be seen, but analysts should pay close attention to the remaking of transit and transport networks in Northeast Asia.