Shashi Lodge is a historic building in Bangladesh’s Mymensingh district. Built in the 19th century during the British colonial occupation, it was once the palatial residence of zamindars (feudal landowners) and now houses the Mymensingh Museum and the Teachers’ Training College for women.

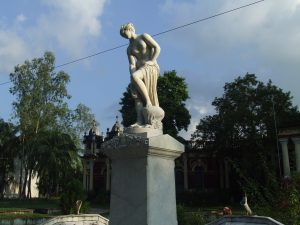

In a garden on its campus, a white marble statue of the Roman goddess Venus imported some 150 years ago, stood in the middle of a fountain. It had survived many regimes — British, Pakistani, Bangladeshi — and rulers whether democratic, military, authoritarian, religious or secular.

On August 6, a day after Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina resigned and left the country in a dramatic chain of developments, a mob forced their way into the premises of the Shashi Lodge and vandalized and beheaded the Venus sculpture. Legendary artist Zainul Abedin’s statue was defaced. There was no other damage to the property, except for these statues.

Overall, about 1,500 sculptures, relief sculptures, murals and memorials have been vandalized, set on fire and uprooted all over the country in just three days — August 5-7.

Many of these were statues of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the founding president of Bangladesh. Many attributed the spree of attacks on Rahman’s statues as an expression of public anger at his daughter, Hasina, who some argue had gone overboard to deify her slain father, from whose popularity she drew her authority.

The destruction, though, was not limited to Rahman’s statues. One of the more prominent indications of the Muslim fundamentalist imprint in the demolition drive is the attack on the statue of Lady Justice on the premises of the Supreme Court.

This statue of the blindfolded lady, similar to the Greek Goddess Themis but draped in a saree, carrying a weighing scale in one hand and a sword in the other, has long been an eyesore to religious groups like Jamaat-e-Islami Bangladesh, Hefazat-e-Islam, Islami Andolon Bangladesh and Bangladesh Awami Olama League who called it an “idol” and therefore unIslamic/anti-Islamic as per Islamic traditions against idolatry.

Many Bangladeshi scholars have repeatedly argued that sculptures are not idols but the religious leadership had their own interpretations.

The Lady of Justice statue was installed on the apex court premises in December 2016. Islamic organizations soon dubbed the initiative a conspiracy to undermine Islam in Bangladesh. After prolonged protests by these organizations, the Hasina government agreed to their demands in May 2017. The statue was removed from its original location and reinstalled at a less prominent place two days later.

On August 6, the Lady of Justice shared the same fate as the Venus statue of Mymensingh. First, the two arms were broken. By night, it had been uprooted. Lady Justice had finally fallen.

Vandals also did not spare the Swadhinata Sangram Bhaskarjya Chatwor (Freedom Struggle Sculpture Square) on the Dhaka University campus on Fuller Road. It is one of Bangladesh’s most iconic works in sculpting.

The main sculpture features the faces of some prominent figures in Bangladesh’s history, holding aloft the national flag. This figure is surrounded by 116 half-busts of significant socio-cultural personalities not only from Bangladesh but also abroad. Sculptor Shamim Sikdar completed this work in 1999. In Bangladesh, the work has been considered a masterpiece. Most of these half-busts were demolished or defaced.

Nearly 500 sculptures were destroyed at the Mujibnagar Liberation War Memorial Complex.

On social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter, many celebrated the destruction, arguing that significant progress had been made towards cleansing Bangladesh of statues. “It looked like a concerted effort to destroy as many statues as possible before law and order is restored. There is an unmissable pattern,” a Dhaka-based journalist told The Diplomat, requesting anonymity.

Statues and sculptures have faced the ire of Muslim fundamentalists for a long time. Some scholars recall that in the late 1970s, activists of Islami Chhatra Shibir, the student wing of JeI, had tried to destroy sculptor Abdullah Khaleq’s work, Aparajeyo Bangla (Unvanquishable Bengal), on the Dhaka University campus.

In October 2008, after Muslim fundamentalist forces like the Murti Protirodh Committee (Idol-resistance committee) and Khatm-e-Nabuwat Bangladesh objected to an under-construction statue of baul (mystic minstrels) practitioners, including Lalon Fakir, vandals destroyed it and forced its removal. Soon after, Mufti Fazlul Haque Amini of Islami Ain Bastabayan Committee (Islamic law implementation committee) declared that all the statues and sculptures in the country would be demolished.

In 2013, Hefazat-e-Islam placed a 13-point demand, including, “Stop turning Dhaka, the city of mosques, into a city of idols, and stop setting up sculptures at intersections, colleges and universities.” In May 2017, multiple Hefazat-e-Islam leaders called for the destruction of all statues across Bangladesh. Some statues came under attack in 2020 as well.

Statues and sculptures targeted this August include a statue of anti-colonial tribal heroes Sidhu and Kanhu. Pravat Tudu, a lawyer and tribal rights leader in Bangladesh said that a new writing emerged at the base of the empty podium: Kalima Chattar (Kalima Square). Kalima refers to some fundamental tenets of Islamic belief.

Political observers fear that a more concerted and organized movement for turning Bangladesh into an Islamic country is on the cards. In a country where Muslims currently comprise more than 90 percent of the population, the battle for secularism has historically been bloody.

The interim government, headed by Nobel Peace Prize winner Muhammad Yunus, includes student agitation leadership and representatives from civil society and a Muslim religious leader. The student leadership and the student-backed government have pledged to pursue a policy against all sorts of discrimination and uphold secular democratic principles.

However, the freedom from suppression and state oppression that Bangladesh has witnessed since Hasina’s fall has also made space for undemocratic, fascist and fundamentalist elements to raise their heads.

While the statue and sculpture vandalism spree ended by August 8, it was followed by a series of incidents in which teachers in colleges and universities were forced to resign. In one incident, a professor who had earlier objected to Islamic prayer events inside the university campus was forced to resign and students also forced him to listen to Quran recitals. Several Sufi shrines, called Mazars, have been vandalized.

On August 30, speaking at a public rally, Islami Andolan Bangladesh leader Syed Faizul Karim said, “Long Live Islamic fundamentalism. We believe in Islamic fundamentalism. None has been able to do politics excluding Muslim fundamentalists and none shall be able to.”

Among other incidents that a section of Bangladesh’s civil society members consider warning signs are the public rallies and poster campaign by the banned terror group, Hizb ut Tahir and the release of Mufti Jashimuddin Rahmani, chief of the Ansarullah Bangla Team, an Al-Qaeda-inspired militant outfit renamed as Ansar al Islam.

On August 1, at an event organized by Bangladesh Policy Discourse, a newly launched banner, Hizb ut-Tahrir (HuT) ideologue Muhammad Zobair was the main speaker. Islamic speaker Enayet Ullah Abbasi called for discarding the Bangladesh Constitution and establishment of the Sharia laws. Supporting HuT, Abbasi said, “People of the country want Khilafat (Caliphate).” Another speaker named Helal Talukdar said while supporting HuT, “Democracy cannot liberate people. Caliphate can.”

Bangladesh’s new political leadership does not want to take a hard approach against any force at this moment, as they say they are still focused on healing people from the gross undemocratic and authoritarian excesses of Sheikh Hasina’s regime. Since Hasina had turned Bangladesh into a police state, they don’t want to follow Hasina’s path, a leader of the Students Against Discrimination (SAD) platform that led the anti-Hasina uprising told The Diplomat.

Ganatantrik Chhatra Shakti (Democratic Student Force), the main force behind SAD, has repeatedly said that they want to bring Bangladesh out of the secular-fascist and Islamic-fascist binary and build a nation where atheists, liberals and religious conservatives can coexist. However, according to a Dhaka University scholar, if not dealt with effectively right from the beginning, all the achievements of the mass uprising will be usurped by anti-democratic forces. “If you (interim government) do not want to use the police to deal with terror groups and undemocratic forces, you need to build powerful public opinion against them. As of now, the counter-fundamentalism initiatives are not worth mentioning,” the scholar said.