The notion of the Global South has been characterized as “an intellectually elusive but emotionally rich term.” The multifaceted term Global South can refer to over 120 countries. It is used to describe regions and nations suffering from widespread poverty and deprived of economic well-being, but also as a political concept for countries resisting Western hegemony and countering the legacy of colonialism. The countries that are a part of the Global South, though, are extremely diverse, so it can be fraught to consider Global South countries as a monolith.

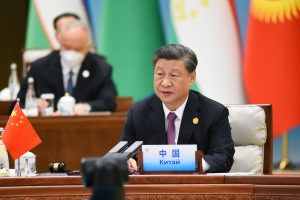

The Global South is central to China’s foreign policy. In the Global South, Beijing wishes to expand its influence to counter the U.S.-led rules-based order and thereby reshape the international security order while promoting an environment conducive to China’s economic expansion. China has attempted to achieve this by promoting its spectacular economic development as an exemplary model for other countries and by offering an alternative to Western engagement in the Global South.

These efforts include the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) where more than $1 trillion has been committed to infrastructure investment in more than 140 countries and territories. Most recently China has launched three new initiatives, the Global Development Initiative (GDI) in 2021, the Global Security Initiative (GSI) in 2022, and the Global Civilization Initiative (GCI) in 2023, as a means of promoting core principles such as mutual respect, peaceful coexistence and win-win cooperation.

The five Central Asian countries – Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan – are part of the Global South. Central Asia, although often considered a regional bloc, is made up of countries with diverse histories, cultures, political traditions, natural resource endowments, and development paths. China’s foreign policy toward these countries has had contrasting results over the years, with the case studies of Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan exemplifying these differences.

China’s Strategy in Central Asia: The Cases of Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan

The differences between Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan and the contrasting impacts of China’s foreign policy in both countries allow for fruitful analysis of China’s challenges and opportunities in the Global South. This can be illustrated in the disparity between Kazakhstan’s yearly GDP of $264.42 billion and that of its neighbor, Kyrgyzstan – $13.99 billion. Kazakhstan’s per capita income is $14,780 in 2024, which is almost eight times bigger than Kyrgyzstan, at $1,920. The size of each country’s economy has been a major factor in determining China’s impact.

China has made significant investments in Kyrgyzstan through both foreign direct investment (FDI) and loans. In 2023, China outpaced Russia in FDI in Kyrgyzstan with $220.8 million in investment, which is nearly 28 percent of Kyrgyzstan’s total FDI. China’s Export and Import Bank loaned $1.7 billion to Kyrgyzstan, which represents 27.4 percent of the country’s total debt. This makes Kyrgyzstan the country in Central Asia with the highest levels of external debt to China.

Furthermore, in 2023, China was Kyrgyzstan’s top trading partner, representing 35 percent of Kyrgyzstan’s total trade volume. Even though Kyrgyzstan is a member of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), where Russia is a dominant force, its trade share with the EAEU was lower at nearly 28 percent.

Another important feature of the China-Kyrgyzstan relationship is the trade imbalance between the two countries. In 2022, the trade turnover between Beijing and Bishkek amounted to $4.07 billion with Kyrgyzstan importing $4 billion from China while exporting only $60.8 million. This indicates Kyrgyzstan’s clear dependence on China for trade and shows how Kyrgyzstan serves as a transit point for Chinese products to reach Russia, despite the harsh economic sanctions implemented against Moscow.

Since gaining independence, Kazakhstan has pursued multi-vector foreign and economic policies through diversifying its foreign investment flows and avoiding dependence on one particular country. As a result, Kazakhstan is the least dependent on China compared to other Central Asian republics in terms of external debt and possesses a diversified investment profile, including Western investors.

In terms of FDI in Kazakhstan, China ranks fourth, having invested $1.14 billion. The Netherlands invested the most at $8.27 billion, followed by the United States and France. China’s investments represent only 6.4 percent of all FDI in Kazakhstan, and therefore it has relatively little impact on the country’s economy. Although China invests significantly more money in Kazakhstan than Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan’s larger economy lessens Beijing’s impact. Similarly, given the size of Kazakhstan’s economy, its debt to China is considered manageable at $9.2 billion, accounting for about 5.5 percent of its total external debt.

As dynamics with Russia have shifted, China has emerged as a strategic trading partner for Kazakhstan. In 2023, China became Kazakhstan’s top trading partner with a bilateral trade volume totaling $31.5 billion. In comparison to China-Kyrgyzstan trade, Kazakhstan has a far more balanced trade relationship with China as it imports $16.8 billion and exports $14.7 billion. Kazakhstan is also far more diversified in terms of trade, and Italy remains Kazakhstan’s top export destination.

Another point of comparison between Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan lies in their respective security cooperation with China. Over the past seven years, China and Kyrgyzstan have significantly deepened their security cooperation, with Beijing allocating $30.5 million in military aid to Bishkek from 2014 to 2017. China is actively involved in training security officials and strengthening Kyrgyzstan’s army through joint military exercises and aid. China’s military-security strategy focuses on humanitarian aid, military equipment donations, and the implementation of security technologies like the Safe City system, allowing Beijing to expand its influence while maintaining a non-intrusive image.

Similar initiatives are just beginning in Kazakhstan, with Chinese Defense Minister Dong Jun visiting Astana for the first time in April 2024. These bilateral initiatives strengthen the ongoing military-security cooperation through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), to which all three countries belong. The SCO is primarily centered on security-related concerns, describing its main threats as terrorism, separatism, and extremism.

China’s Path Forward

China’s foreign policy has been more successful in Kyrgyzstan than in Kazakhstan. Kyrgyzstan, with a smaller economy and a lack of lucrative natural resources like oil and gas, has sought Chinese investments and consequently needs China as an essential partner for its development.

On the other hand, Kazakhstan has pursued a path of multi-vector diplomacy which has made China only one of Kazakhstan’s many valuable partners. Russia’s war in Ukraine has created distance between Russia and Kazakhstan; Central Asian states like Kazakhstan are now turning toward China as a security and sovereignty guarantor, which is a new role that Beijing could embrace in the region. Given Kazakhstan’s economic position, it is unlikely to develop the same relationship with China as Kyrgyzstan, but China and Kazakhstan will likely continue to develop a mutually beneficial partnership.

Moving forward, there are three important points to keep in mind regarding China’s presence in Central Asia.

First, the shift from the BRI reveals China’s desire to invest in quality over quantity in the Global South, due to a lack of soft power gains and current economic stagnation in China. China’s GDI emphasizes soft power to optimize social impacts, focusing on education, health, IT, and green energy. Furthermore, China wishes to present an alternative to the Western rules-based international order, which was further entrenched by Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Second, China’s economy has experienced economic contraction and a slowdown in growth. China’s economic model faces a rapidly aging population, a real estate crisis, and a dependence on manufacturing and exports. In essence, China is entering “the middle-income trap” at $13,140 per capita income. This demonstrates that China’s economic model is still in a formative stage. The future prospect of China’s success or failure requires President Xi Jinping to show greater adaptability to handle China’s current challenges.

And finally, despite robust investment in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, public perception of China remains low in both countries. A large share of the Kyrgyz and Kazakh populations are against close integration with China. According to the Central Asian Monitor, over 66 percent of the respondents are very concerned and 21 percent are somewhat concerned that Chinese development projects could increase the national debt of Kyrgyzstan. In a similar questionnaire, over 70 percent of respondents in Kazakhstan stated that they have little or no confidence that Chinese investment will create jobs in the country.

Negative public sentiment may stem from inconsistencies between China’s domestic and foreign policies. Xi has stated that China’s foreign policy is based upon principles such as respect for sovereignty and peaceful coexistence. Therefore, China’s domestic policy must be aligned with these principles and this should be reflected in how the authorities deal with issues like human rights, COVID-19, or climate change.

Another inconsistency can be seen in China’s relationship and support for Russia and its war in Ukraine which disregards the importance of the sovereignty of states. Xi and Russian President Vladimir Putin have met more than 40 times in the last 15 years. This poses a problem for Central Asian countries that may be at risk given Putin’s imperialistic ambitions and therefore have aimed to create distance between themselves and Russia.

China has achieved remarkable economic growth and expanded its geopolitical influence under Xi, particularly through initiatives like the BRI and GDI. However, the Chinese model of a state-led economy continues to evolve, and the outcomes of this ongoing process can have a profound impact on Central Asia and beyond.

To gain respect as a global leader, Xi must strategically distance China from Russia and North Korea, while restructuring domestically by loosening control, especially in areas like innovation and political discourse. Additionally, managing delicate issues with Taiwan with prudence and investing in education and global exchanges will strengthen China’s soft power.

Deng Xiaoping’s success was built on his willingness to adapt and be flexible, understanding that strict adherence to “socialism” couldn’t drive economic growth. Having already achieved significant success, it is now time for Xi to show similar resourcefulness and flexibility. China has shown incredible capacity in the recent past to rapidly transform and become a dominant superpower on the world stage. It can once again showcase its tremendous ability to swiftly solve its domestic issues and continue its sustained economic development to the benefit of the world. By achieving a peaceful settlement of the ongoing war in Ukraine and contributing to peace and stability on the Korean Peninsula, China can overcome the current challenges it faces and continue to provide a model for countries in the Global South to emulate.