SRINAGAR — On October 8, amid a nerve-wracking election result reveal in Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), locals yearned to know who the victors were in an election the region had waited for since 2019.

Assembly elections were last held in J&K in 2014 – going by the tenure of the assembly, they should have been held again in 2019. However because of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s decision that year to revoke the constitutional rights and guarantees that guarded the region, the elections were postponed, citing uncertain security conditions.

In 2014, the elections had resulted in an alliance between a regional party, the Peoples’ Democratic Party (PDP), and Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). This alliance was dissolved in 2018 by the BJP, rendering the region without an elected government. The next year, the region was robbed of rights too. J&K was stripped of its autonomy and downgraded from a state to a union territory, ruled from New Delhi.

In this year’s long-awaited elections, held from September 18 to October 1, the voters in J&K ousted the PDP and did not favor the BJP much. In a thumping majority, they gave their mandate to another regional party – the Jammu and Kashmir National Conference (NC). The NC has ruled the region in the past, but since their last tenure, which ended in 2014, the BJP has severely altered the rules and realities that govern Kashmir.

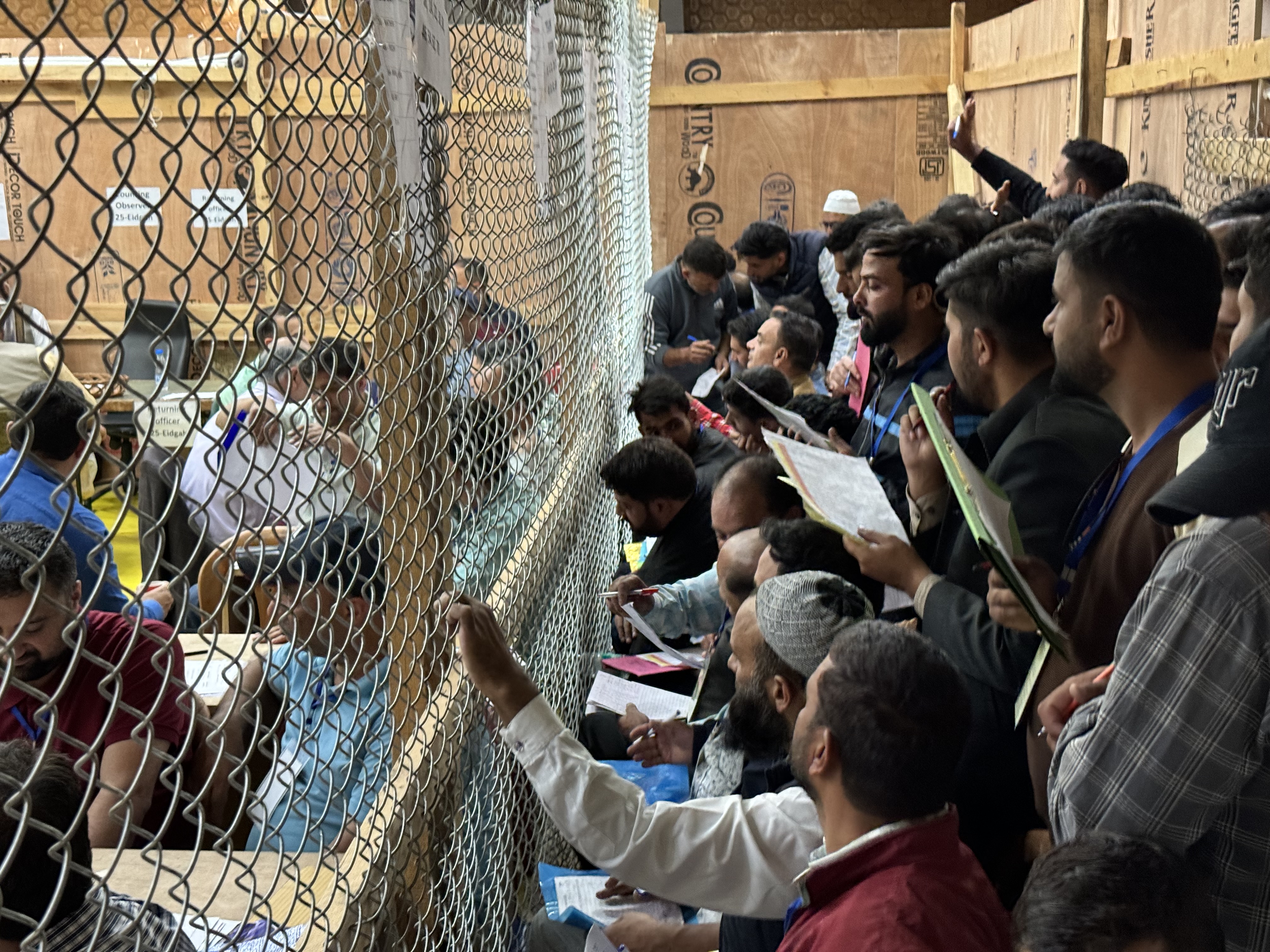

Votes being counted for the Jammu and Kashmir Assembly Elections in Srinagar. Photo by Ahmed Zubair.

Vote Against Violence, Silence

In Kashmir’s Pulwama, Nusrat Jan, 32, voted for the first time in her life. She belongs to Pulwama’s Karimabad, an area known as a hotbed of anti-India rebellion and election boycotts. But ever since her husband was whisked away by the authorities and jailed under India’s stringent anti-terrorism laws, her perspective about having an elected Kashmiri leadership has massively changed.

“I want our leaders to at least help me in my fight for my husband. There are many like him who are in jails for no reason. I only voted so that I can hold someone accountable and seek help,” Jan explained to The Diplomat.

Since 2019, 2,300 Kashmiris were reported to have been arrested under the same anti-terrorism laws that hold Jan’s husband hostage. The people arrested include daily wage workers, university students, journalists, and voices that critique the Modi government.

Other locals also hope that the elected representation in Kashmir could at least be in a position to call out the Modi government for its harassment and intimidation against dissenting voices.

Dr. Raja Muzaffar Bhat, a Srinagar-based social activist has spent years of his life holding authorities accountable and insisting they respect the rights of Kashmiris as provide by the law. In these elections, he believes Kashmiris were plainly voting out of the anger of being silenced by the BJP.

“For more than five years, we had no representatives, no democratic set-up. This mandate has not gone to the NC; rather it is [a vote] against the atmosphere of fear and clampdown created by the BJP. Several non-voters have voted for the first time in their lives in these elections, only and only to show their power to BJP and its allies,” Bhat said.

Another voter in Kashmir’s Ganderbal, Minhaj Malik, 24, was stunned to see fellow voters queuing up at polling stations as early as 8:00 in the morning. “I was shocked. All my life I have seen people mostly sidelining these occasions and with great reasons. But today, people are desperate to keep the BJP out of Kashmir,” Malik said.

Malik, a university student and a first-time voter, described his reasons for casting a ballot: “Since 2019, our issues and grievances have been ignored. We were completely being run by officers, who do not resolve our issues and in that case, we had no elected representatives to turn to,” he said.

But in Malik’s case, the “issues” he highlighted were purely development-oriented. In this reorganized region, locals point to a lack of basics facilities.

Kashmiri women sit on a sidewalk in Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir’s capital, Srinagar. Photo by Ahmed Zubair.

A Lieutenant and Governance Limitations

To understand why a region that previously was known for electoral boycotts turned out in droves to vote for their preferred candidates, one must circle back to 2019, when the BJP arbitrarily scrapped Kashmir’s constitutional guarantees. From being a state, the region was reduced to a union territory, where the centrally appointed lieutenant governor was made superior over every entity that existed in the region. By the virtue of this set-up, powers of the elected leadership to exercise control over the region now sit in a limited and restricted scope.

Ever since the region was reorganized in August 2019, the Modi government bestowed itself with the power over the law enforcement agencies and its representative – the lieutenant governor.

The office of the lieutenant governor and its ambit of power casts a gloomy shadow over the region’s local government. Left with miniscule control over the affairs of the region, the Jammu and Kashmir Assembly can make laws in areas such as such as agriculture, hospitals, municipal corporations, land revenue, local government institutions, public health, and sanitation. Even these bills would await the LG’s nod before they actualize as laws.

“People were waiting for a chance to express their resentment towards the coercive changes, but the real levers of power now lie outside the scope of the elected leadership,” Anuradha Bhasin, a veteran journalist, and author of “A Dismantled State: The Untold Story of Kashmir After Article 370,” told The Diplomat.

Bhasin also explained that despite the victory of a regional party, the optics of letting Jammu and Kashmir participate in the long-awaited elections fall apart when one reads into the kind of power that the LG wields now. “That makes it frightening, because this is a very fragile region, where people have very different political aspirations,” she said.

Kashmiri academic and author Dr. Sheikh Showkat Hussain believes that people do not have much hope, given that the newly elected leadership will have little authority and will be largely dependent on the LG and the central government – ruled by the same BJP that Kashmiris rejected in both the assembly elections and the parliamentary vote earlier this year.

Still, Hussain said that Kashmiris perceived that they may have some respite from the authoritarian set-up unleashed in J&K post 2019. “The results signify that despite the manipulation by redrawing constituencies… Kashmiris rejected whatever was done here,” he explained. “Now they have expectations that the elected leaders will restore the autonomous status of the region, that existed before 2019.”

NC leader Omar Abdullah, who is expected to be the new chief minster in J&K, has pledged to pursue a restoration of statehood for the region.

“It is true that the people of Jammu and Kashmir will be electing an assembly that doesn’t have nearly as much power as the previous ones, but it is not without power,” he told The Diplomat’s Anando Bhakto in an interview ahead of the election.

National Conference workers celebrate their party’s victory in Srinagar on October 8, 2024. Photo by Ahmed Zubair.

Democracy or Despair?

Since August 2019, several local leaders have been coerced to live a lifestyle of captivity even within their own homes. Mirwaiz Umar Farooq, Kashmir’s chief cleric and chairman of All Parties Hurriyat Conference, is one of them. A religious and political figure revered across Kashmir, Farooq has had to deal with Delhi’s own definition of democracy by being caged in his own house by the authorities for reasons best known to them.

For Farooq, the election results reflect a consolidated message of strong disapproval to the drastic unilateral changes made in August 2019, which he believes led to disempowerment and deprivation of people’s rights.

“I hope those elected, though with very limited powers, heed to the voters’ message and are able to restore people’s civil rights. It will be a constant challenge for them. But they can give resistance to decisions that furthermore disempower people and increase the role of local population in its own governance,” Farooq told The Diplomat.

He added that he hopes that by having local representatives, people will get an opportunity to be heard on their daily life issues – including an alarming unemployment rate, which has not been tended to yet despite the BJP’s boasts about improving J&K’s economy. Unemployment in the region has been at an all-time high.

Despite the increased voter turnout, not all Kashmiris chose to vote. For some, the disillusionment is simply too great.

Faisal Dar, 32, did not vote in these elections. From Srinagar’s Downtown, Dar said no one in his family voted. “We have never voted; we will never vote. Votes don’t bring back the dead,” he declared.

Amid the high voter turnout for Kashmiris, the tension beneath the surface cannot be ignored or overlooked. Some Kashmiris, seven decades after Kashmir’s accession to India, still believe that their rights lie outside of Indian democracy.