The Royal Thai Air Force (RTAF) wants to reach the stars – quite literally – with plans to rebrand itself as the Royal Thai Air and Space Force. Alongside this name change, a National Air and Space Interests Coordination Center will be established in order to oversee both Thailand’s internal and external aerospace defense activities.

The announcement was made last week by RTAF spokesperson Air Marshal Prapas Sornchaidee, following the first defense commanders meeting of the 2025 fiscal year. Before any of these proposals can officially take flight, legislative changes will be necessary. If all goes as expected, the process should be finalized by 2028.

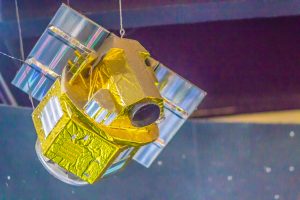

Thailand’s space agenda has traditionally been confined to research and socio-economic applications. In these areas, and in relative terms within Southeast Asia, Thailand is among the most advanced and active nations. Through its Geo-Informatics and Space Technology Development Agency (GISTDA), founded as a public organization in 2000, Thailand has become a trailblazer in earth observation technology. The THEOS-1 and THEOS-2 satellites, launched in 2008 and 2023 respectively, have contributed immensely to the country’s agriculture and environmental monitoring, urban planning, and disaster management. The next generation of THEOS, projected to launch by 2027, is being mostly if not entirely developed and assembled domestically, demonstrating Thailand’s progress in both technical expertise and infrastructure.

GISTDA’s Assembly Integration and Testing Center in Thailand’s Eastern Economic Corridor, home to the making of THEOS-3, has emerged as an important facility for both private space start-ups and the RTAF. It is here that Thai Universe-1, reportedly the RTAF’s first self-made nanosatellite crafted using affordable commercial-grade components instead of expensive space-grade ones, is undergoing testing.

The RTAF’s foray into space took its first major step when Napa-1, contracted to the Dutch firm ISISPACE, entered orbit in 2020. The minimally modified Napa-2 quickly followed in 2021.

The RTAF’s 80-page white paper, released earlier this year as an update to the 2020 edition, dedicates substantial attention to the growing significance of space. It highlights the precarious vulnerability that comes with reliance on space assets as major powers clash. At the same time, it stresses smaller powers’ need to harness space technology for enhanced military intelligence. This is crucial for the RTAF’s effective long-term operations across three designated areas: the global area of interest (where Thai citizens are located), area of influence (Southeast Asia), and area of responsibility (Thailand’s sovereign territory). The RTAF’s area of responsibility, which includes Thailand’s flight information region and exclusive economic zone, totals 1,979,722 square kilometers.

So far from being an abrupt and hollow change as some might perceive, the RTAF’s latest efforts reflect the gradual consolidation of Thailand’s military space interest, which is modest and defensive in nature. This context explains why the Space Force is not being formed as an independent armed branch, but will remain attached to the Air Force.

The proposed National Air and Space Interests Coordination Center is clearly modeled after the Thai Maritime Enforcement Command Center (Thai-MECC), Thailand’s centralized body for maritime security governance. As I wrote in an article published by the CSIS Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, Thai-MECC has proven highly effective in tackling threats to Thailand’s maritime interests, as it is legally empowered to conduct surveillance and investigations, and to mobilize resources from the Royal Thai Navy (RTN) and six other government agencies. Manpower isn’t much of an issue in the sense that Thai-MECC personnel are rotated from various agencies, avoiding the additional costs of new hires.

An interesting point of observation will be the civil-military dynamics of the new coordination effort. The Thai-MECC is dominated by the RTN, whether on paper or in practice, leaving civilian agencies somewhat in the background. This arrangement hasn’t really raised questions because, even as the scope of maritime security has broadened markedly, the traditional military-centric lens on territorial defense remains intact. In contrast, the space domain has always been more closely tied to science. As such, it makes sense to think that the RTAF, while central, may not exert the same level of dominance in the up-and-coming Air and Space Interests Coordination Center as the RTN does with the Thai-MECC.

The RTAF stands as the least conservative branch of Thailand’s military, as reflected in its relative openness to commanders with international qualifications and its ahead-of-the-curve publication of a comprehensive white paper. Both the RTN and the Army have shown a strict preference for domestically educated commanders, and it was only in the past two years that they began publishing their white papers. The restructuring initiatives currently underway are yet another demonstration of the RTAF’s commitment to staying at the forefront of Thailand’s military modernization.