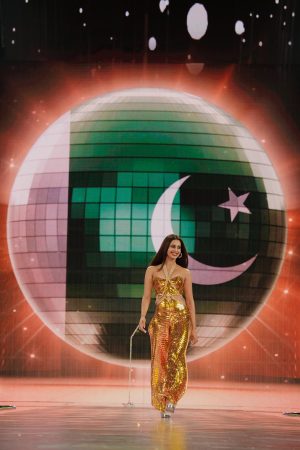

I recently watched a video of a confident Pakistani woman, Roma Michael, dressed in a striking metallic gold bikini with matching gold gloves, walking the ramp at Miss Grand International 2024. “What a proud moment for Pakistan,” I thought. The journalist in me wanted to learn more about her, but as I was midway through my research, I came across news headlines revealing that she had deleted the video after facing a wave of backlash.

While it wasn’t surprising given the track record of conservative crowds in Pakistan, the intensity of the threats horrified me. Some people even feared for her safety, urging her not to come back to Pakistan and to seek asylum elsewhere.

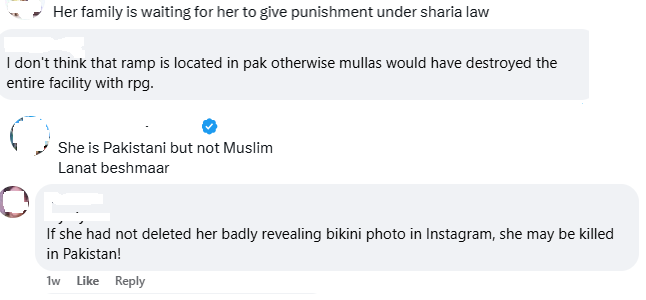

Comments ranged from harsh judgments to outright threats. Some accused her of tarnishing Pakistan’s reputation and called for religious edicts (fatwas) against her. Others claimed that her family should punish her under Shariah (Islamic law), while some pointed out that although she is Pakistani, she isn’t Muslim, expressing their disdain with remarks like “Lanat beshumar” (countless curses). A few sarcastically remarked that if the runway were in Pakistan, religious extremists might have destroyed the venue with weapons.

The vitriol was so high that it made me wonder what Michael would have faced if she hadn’t deleted the video.

This is not the first time that a model representing Pakistan on the global stage has faced this level of criticism – we saw something similar in the case of Erica Robin when she dared to be the first Pakistani to ever grace the stage of Miss Universe in 2023. Her entry into the competition was deemed “shameful” by Senator Mushtaq Ahmed of the Jamaat-e-Islami party, with then-caretaker Prime Minister Anwaar-ul-Haq Kakar even ordering a probe into the matter.

So it wasn’t surprising to see the harsh criticism conservatives directed at a Christian minority model for wearing a bikini – a taboo outfit in Islamic Republic of Pakistan – in the Miss Grand International pageant, an annual global beauty contest known for promoting peace and opposing violence.

Roma Michael’s Story: Between Fashion and Tradition

Roma Michael is a Pakistani Christian model and actress who started her career in 2013. Despite challenges as a religious minority, she gained recognition through collaborations with designers like HSY and Nida Azwer and appearances at major fashion events. She has also represented Pakistan internationally and appeared in films and TV shows, solidifying her place in the fashion and entertainment industry.

“Growing up, I dreamed of participating in a major beauty pageant, and when the chance came, I embraced it. I believe this is just the beginning, and I’m excited to pursue more international projects,” Michael told The Diplomat.

“The overall experience was like a roller coaster – one of the most challenging times of my life. I faced some tough obstacles, such as my luggage being misplaced and the high level of competition. But through it all, I learned a lot, met people from different backgrounds, and gained confidence.”

Speaking about the backlash to her video, she said, “Yes, I was aware that public platforms come with both positive and negative feedback, so I expected some backlash. In today’s world, even a simple post can trigger a reaction, so it’s quite common.

“When you put yourself on display publicly, you’re bound to receive both positive and negative criticism. If you’re someone who’s easily affected by others’ opinions, being in the public eye might not be the right choice. Some of my actions may have unintentionally hurt people’s sentiments, which was never my intention. Moving forward, I aim to be more mindful of my actions and continue to make a positive impact.

“To the critics, I’d say this: Haters can often be your biggest supporters, whether they realize it or not. So, thank you for the motivation, and much love to you.”

Why Is the Bikini So Controversial in Pakistan?

In Pakistan, the idea of modesty is deeply rooted in both culture and religion. For many, how a woman dresses is more than just a fashion choice – it’s a reflection of her values, her family’s honor, and even her connection to religious teachings.

Modesty is often tied to clothing that covers the body and is considered appropriate by Islamic standards, which many in Pakistani society hold very closely. Michael’s decision to wear a bikini on an international stage went against these expectations.

What makes this even more intense is that clothing in Pakistan, especially for women, isn’t just about personal choice – it’s a symbol of morality. When a woman wears something revealing, it’s often seen as a statement that challenges traditional values. Michael’s bikini brought all these beliefs to the forefront, sparking strong reactions.

It’s not just bikinis; women’s clothing has always been a hot topic in Pakistan. Time and again, we’ve seen actors and models get slammed for what they choose to wear, whether at events or just in general.

Take actress Alizeh Shah, for example. In 2021, she faced severe backlash and mockery for wearing a backless and strapless black gown at the Hum Style Awards. Then there was Saba Qamar, whose white outfit at the 22nd Lux Style Awards sparked a social media frenzy. Even Mahira Khan wasn’t spared; she was trolled online when she posted a photo in a lime green skirt and striped blouse that revealed her bare back during a vacation.

These examples show how clothing choices, especially for women, stir strong opinions and judgment in Pakistan. Fashion can easily become a target for criticism by religious conservatives.

What I find even strange is that even when women wear shalwar kameez – the national dress of Pakistan and supposedly the “epitome of modesty” – they still face backlash. Take Mehwish Hayat, Ayesha Omar, and Hina Altaf, for example. They wore shalwar kameez to celebrate Pakistan’s Independence Day, but people were more interested in speculating about what they were wearing underneath. It goes to show that no matter how “modest” a woman’s clothing is, religious conservatives in Pakistan will always find something to pick apart.

And, it’s not just models or actors who face this; I’ve experienced it firsthand. In an article I wrote for The Diplomat, I shared my encounter with Pakistan’s intense blasphemy obsession, where even a simple printed shawl drew sharp criticism. It was a stark reminder that any woman, no matter her profession or public profile, can be targeted for what she wears. This isn’t just about fashion; it’s about a culture that often ties a woman’s worth and morality to her appearance, making personal expression a risky act.

“When the foot soldiers of patriarchy catch a whiff of any woman exercising her agency, sirens start going off, and, like clockwork, the shaming begins,” explained Sajeer Sheikh, a freelance journalist from Karachi. “And the vitriol is never, ever tame – if one can even imagine such a form of chiding. For the politically motivated, it is fodder to feed the narrative that conservativism’s loosening reign is destroying our social fabric. For those who wish to uphold pillars of the patriarchy, it is an excuse to wield their unchecked anger.”

Michael’s specific situation gets further complicated by the nature of beauty pageants, which Scheherazade Noor, an anthropology and gender studies researcher at Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS), critiqued for promoting “eurocentric beauty standards” and superficial empowerment:

Beauty pageants monetize unrealistic, eurocentric beauty standards by pitting women against each other to conform to these ideals. [They] are premised upon ‘pretty privilege’ and sexual objectification, with no genuine feminist impact. Claims of empowerment through choice don’t make the pageants feminist; they uphold the patriarchal standards that used to put the average woman down, reinforcing barriers rather than breaking them.

Beyond the Dress: The Cost of Being a Woman in Pakistan

In many rural areas of Sindh, Punjab, and Balochistan, where education levels are lower, conservative beliefs run deep. People often follow religious practices and the teachings of local clerics without question, and this has led to harmful ideas, especially for women, that can sometimes turn deadly.

Take Qandeel Baloch as an example. She was killed by her own brother after posting pictures of herself in a bikini. Qandeel’s brother felt pressured by the community to “protect” the family’s honor. He succumbed to peer pressure following many sermons against the outrage of modesty by religious cleric, Mufti Abdul Qavi.

This tragic story was shared in the drama “Baaghi” and inspired a film to show just how dangerous these beliefs can be. But while shows and films like “Zard Patton ka Bun,” “Nayab,” and “Wakhri” aim to raise awareness, they mainly reach people in cities. Rural communities, where change is really needed, often miss out on these messages.

Violence against women is a serious issue in Pakistan, especially in rural areas, where 56 percent of women face physical violence. Urban areas report even higher lifetime rates: 57.6 percent have experienced physical abuse, 54.5 percent sexual abuse, and 83.6 percent psychological abuse. There have been many shocking cases, like a father and brother in Toba Tek Singh who raped and killed a young woman. In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s Kohistan district, a video of men and women dancing at a wedding led to a tribal death sentence for four women and two men. And in Kolai-Palas near the Afghan border, village elders ordered the killing of an 18-year-old girl over a photo posted to social media.

Even cities have their share of violence. In Lahore, a pregnant woman was stoned to death by her family outside a court in an honor killing. Similar stories come from Karachi, showing that violence against women is widespread.

Why does this happen? A key contributor is a lack of education and a tendency to blindly follow ancient cultural traditions, reinforced by religious teachings. Low impulse control, mental health issues, and Bollywood movies that romanticize harassment add fuel to the fire and make it a lethal combination that women often fall victim to in Pakistani society.

Many women are raised to believe that their main job is to serve their husbands and endure abuse to keep the family peace. That’s why saas-bahu dramas are so popular in Pakistan – they show women trying to deal with difficult in-laws and reinforce this idea.

Is Women’s Autonomy Still a Far-Fetched Reality?

When women in Pakistan make bold decisions about their bodies or express themselves freely, the backlash is often severe. Qandeel Baloch and Veena Malik both faced relentless criticism and character attacks from religious clerics and society at large. The pressure was so intense that the former was killed and the latter was forced to step away from her career in show business and adopt a more religious, conforming image to avoid further judgment.

It didn’t stop there. When private videos of celebrities like Meera and Rabi Peerzada were leaked, they faced a wave of public shaming that silenced them and pushed them into isolation. In each of these cases, the message was clear: Women who step outside societal expectations, even unwittingly, are to be punished, whether through public humiliation, career destruction, or even threats to their safety and very lives.

With all this context in mind, the controversy around Roma Michael’s bikini isn’t just about what she wore. It’s part of a bigger picture of how women in Pakistan are constantly judged for their choices whether they participate in a beauty pageant or simply choose to express themselves the way they want.

“Being a woman alone is enough to face backlash,” said Romana Bashir, a Pakistani community activist for women and minority rights and religious tolerance. “This isn’t a minority-versus-majority issue; it’s a male-versus-female issue, where men become so dominant that they begin to see women as their property. The level of extremism has increased so much here that we take on the so-called ‘right to kill,’ sometimes because she is a woman, sometimes because she’s a minority.”

The Penal Code of Pakistan also doesn’t seem to support women’s choice to express themselves freely. Under Section 290 of the Pakistan Penal Code (1860), if a citizen accuses a woman of “committing a public nuisance” or “engaging in obscene acts” (Section 294), she may face imprisonment, a fine, or both. However, a source working within Pakistan’s legal system informed me that some of these laws are in the process of being amended under the supervision of Deputy Prime Minister Ishaq Dar, so there is at least some hope.

“All modern societies have fought on this battleground in these two same opposing camps and after much struggle came to terms and moved on to other battles,” according to Waqas Rabbani, a digital marketer and entrepreneur from Pakistan. “Pakistan being a young country is simply going through its teething issues.”

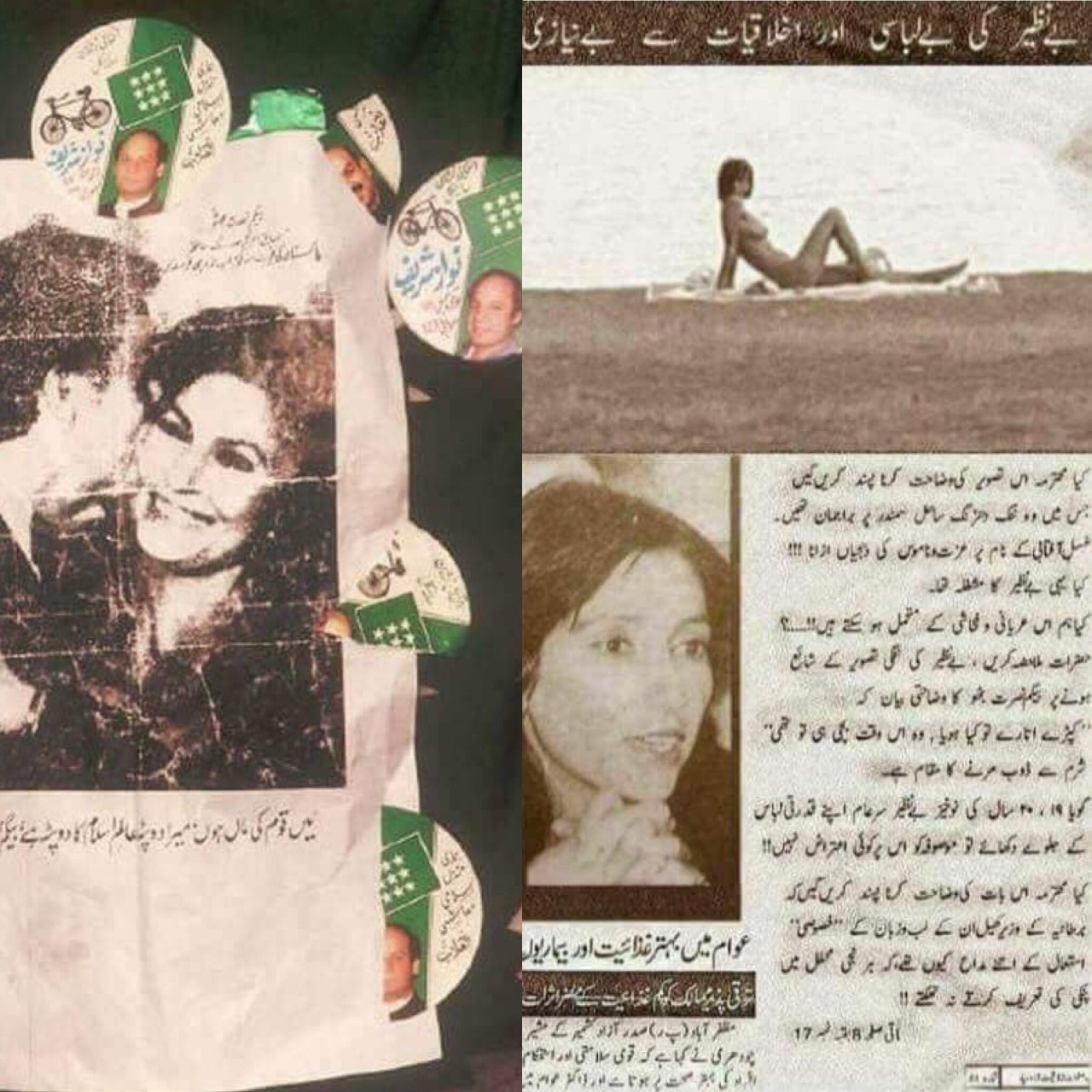

It might seem like Pakistan is the worst place for women, but remember, this is the same country that elected a female prime minister, Benazir Bhutto, before many Western nations did. Yet let us not forget that she too was assassinated – both in character and eventually in body – by her rivals, showing the complicated reality for women in Pakistan.

The newspaper clipping used to try and publicly humiliate Benazir Bhutto for visiting a nude beach with friends. Image source: X.

Here’s the translation of the Urdu text in the news clipping:

Would the honorable lady care to explain why she was lounging on the beach, barely clothed? Flaunting modesty under the guise of sunbathing! Was this truly the pastime of Benazir? Are we supposed to tolerate such nudity and vulgarity? Gentlemen, observe the explanatory statement made by Begum Nusrat Bhutto upon the publication of Benazir’s revealing photograph: “What if she took off her clothes? She was only a child at that time.” This is a moment of utter shame! It appears that a 19 or 20-year-old Benazir found no problem in openly showcasing her natural attire. Would the honorable lady care to explain why the British sports minister was so enamored with her verbal skills that he couldn’t stop praising Pinky at every private gathering?

When even the woman who eventually became the first female prime minister of Pakistan was not free to be who she was, I can’t help but worry. In a country where a woman’s autonomy is so often disregarded, the vitriol directed against Roma Michael cannot be viewed as simply idle threats. Other women have face gruesome fates, from Mukhtaran Mai, who survived a brutal gang-rape, to Qandeel Baloch, who was killed in the name of honor, to even Benazir Bhutto, whose fight was met with violence?

I can only hope Michael receives better treatment, so we might set a new and better example for the future.